Northeastern University students win MITRE embedded capture the flag competition to design and hack secure gaming consoles

Less than a year after the Nintendo Switch was released, people had already discovered ways to hack the portable gaming system.

Like many of its predecessors, the console had a small gap in its security, and attackers were ready to take advantage of it. If console developers want to protect their intellectual property, they will need cybersecurity experts who understand what hackers are capable of and can design near-perfect systems to keep them out.

A group of students from Northeastern may be up to the challenge. In a recent competition, the group successfully designed a prototype gaming console that stopped every attempted attack. The students also proved to be impressive hackers themselves, defeating the security measures in the systems designed by the other teams.

“As soon as our design got accepted, it took us maybe three days until we hacked everyone,” says Dennis Giese, who is a visiting scholar at Northeastern and will be starting as a doctoral student in cybersecurity this fall. “It turned out very well.”

The Northeastern team won first place overall in MITRE’s Embedded Capture the Flag competition, which challenges students to design secure systems and then collect a series of digital ‘flags’ by hacking different aspects of their competitors’ systems.

“This year, they had to develop a gaming system,” says Guevara Noubir, a professor of computer sciences and director of Northeastern’s cybersecurity graduate program, who advised the group. “But you don’t want someone to cheat. You don’t want someone to run a game that he didn’t pay for. You don’t want one user to play a game for another user.”

The Northeastern team, which included Geise, Erik Uhlmann, William Tan, Sreeharsha Potu, Christopher Brown, and Jingyi Situ, was the first team in the four-year history of the competition to successfully defend all of its own flags and collect every flag from every other team. In addition to first place, the Northeastern students received the “Iron Flag” award for successfully keeping all attackers out of their system, and the “Best Documentation” award for ensuring that their code was clear and easy to understand, as well as impossible to beat.

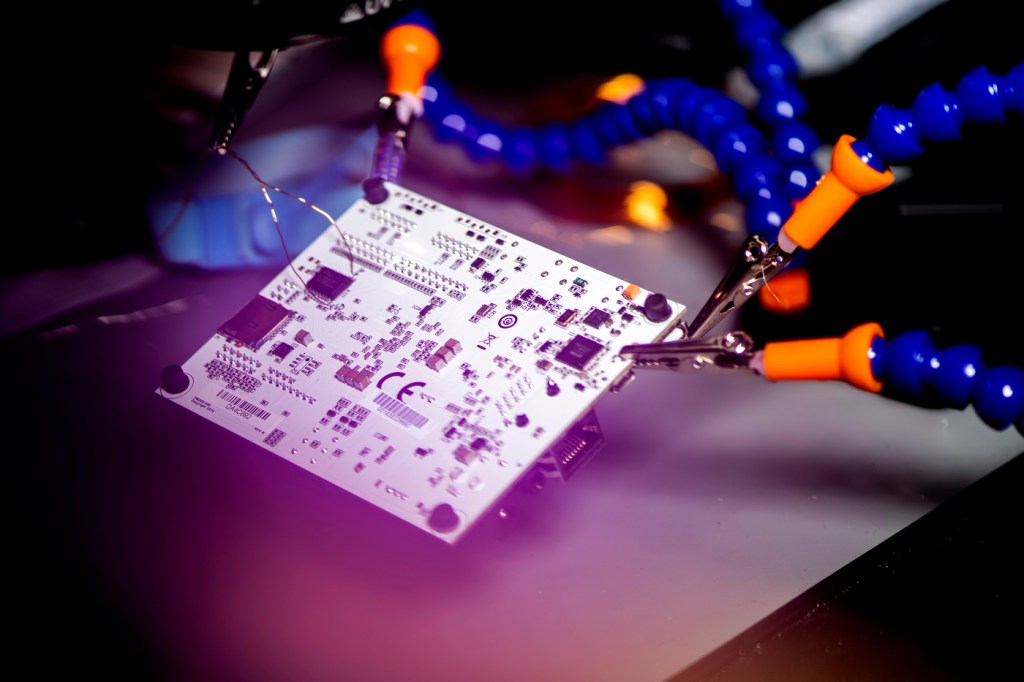

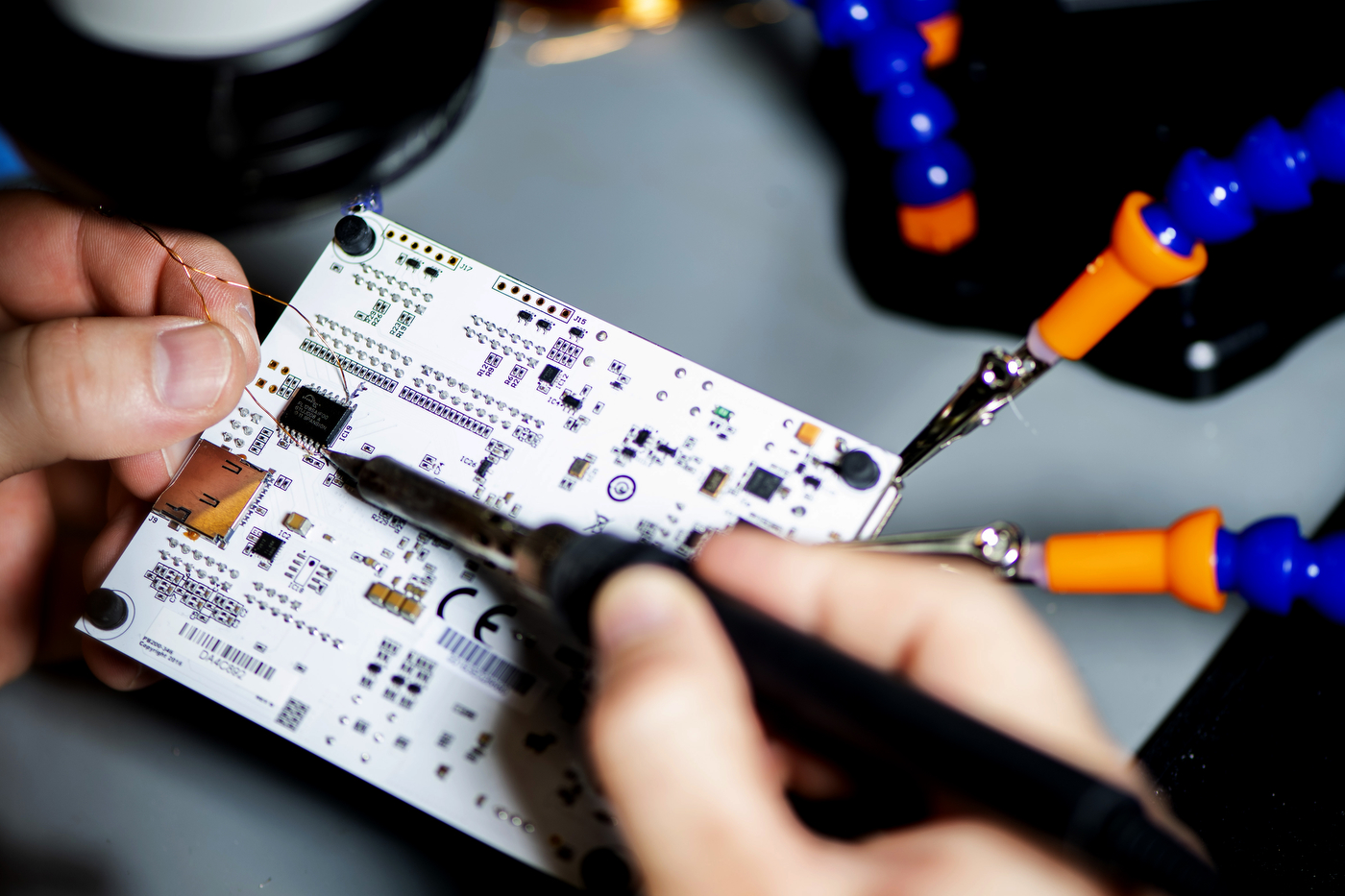

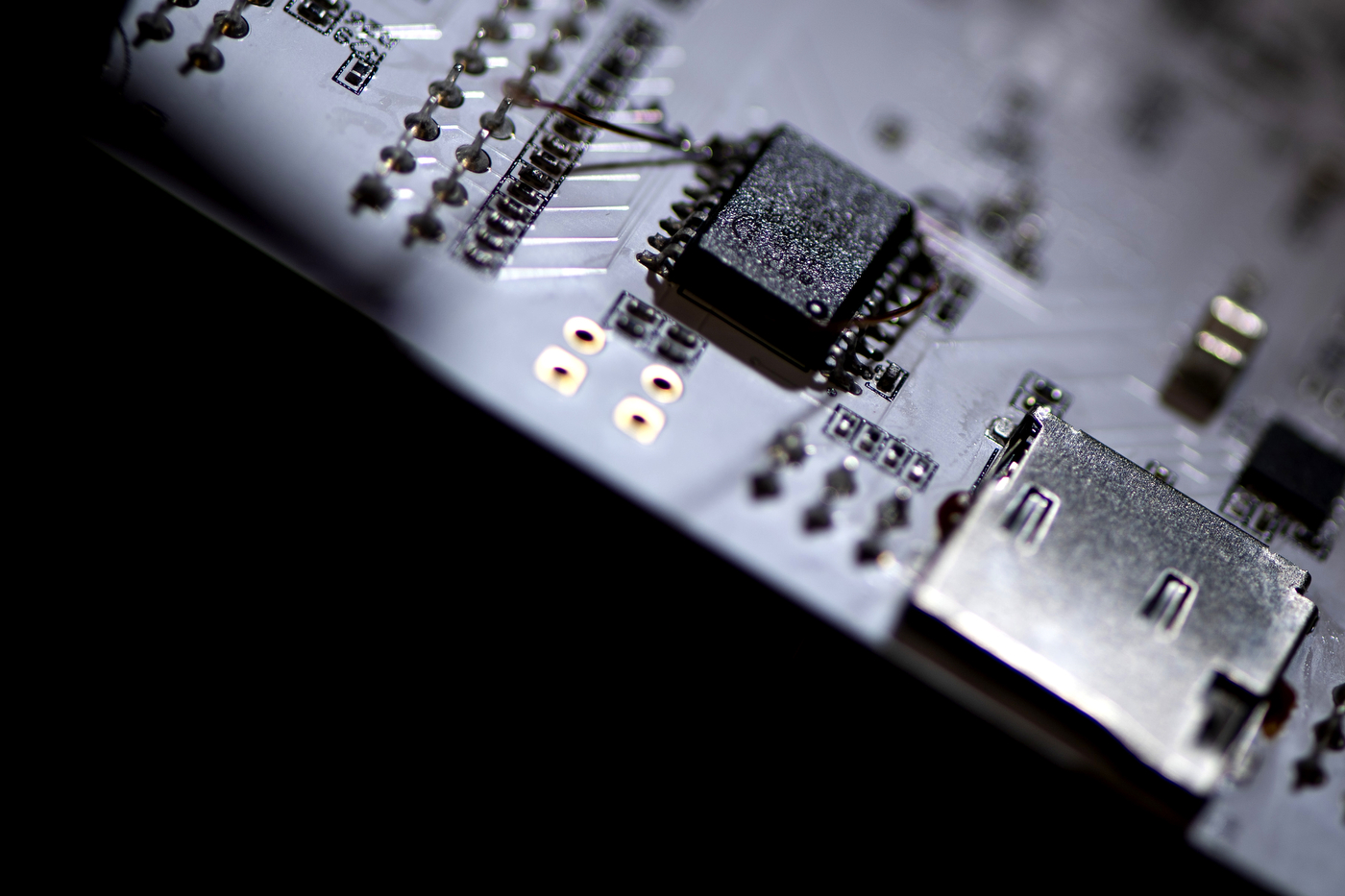

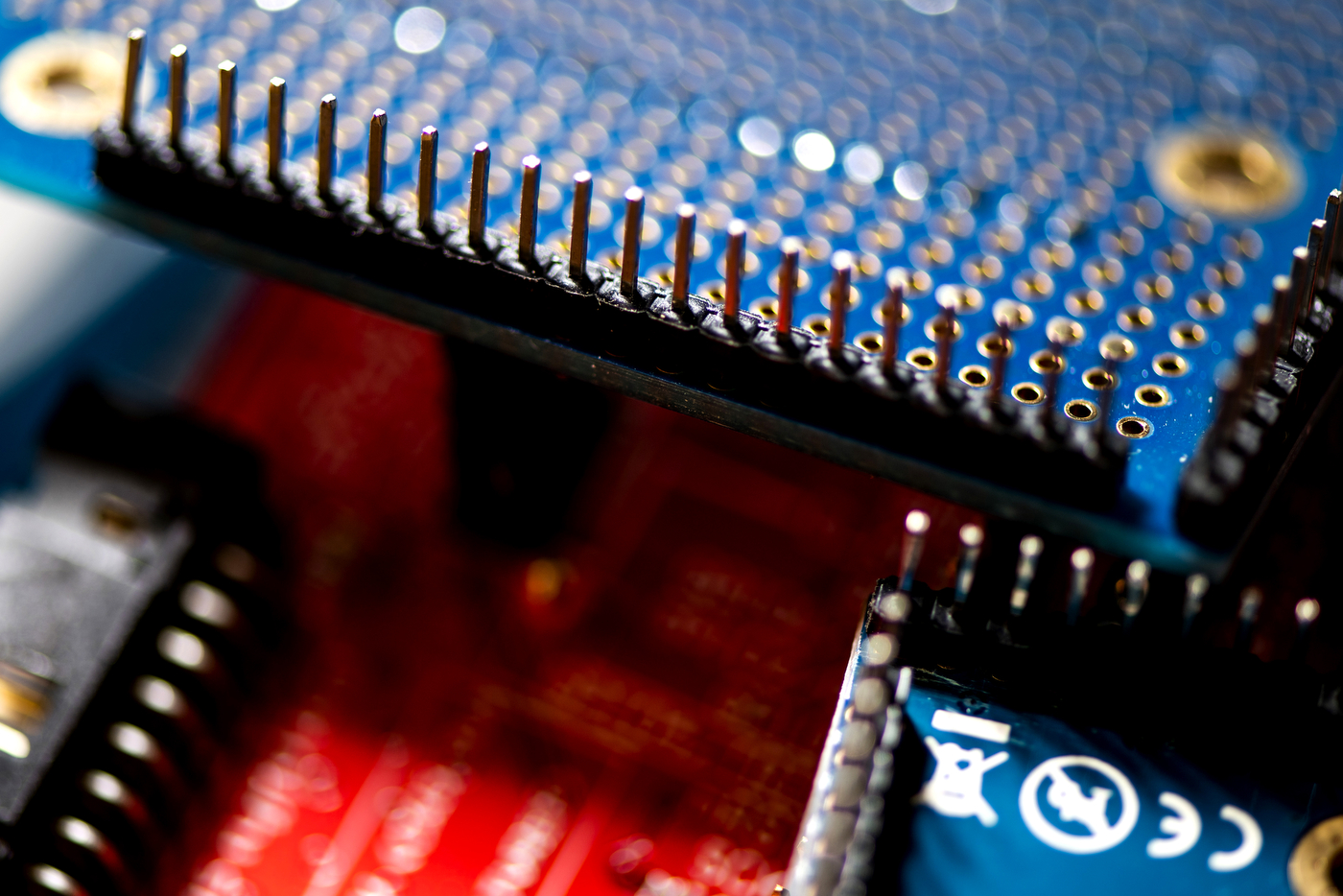

The competition, which took place over three months, was broken down into several phases. In the design phase, the students were given pre-made circuit boards with the necessary hardware for their task and unsecured software as a reference. They had the option to try to secure the given software or design their own from scratch. Giese and his teammates were the only students who opted to design their own, so that their security was built in from the beginning.

“We spent hundreds of hours doing that, maybe more,” Giese says. “But at the end of the day, the decision to not go with the reference implementation was how we avoided being hacked. Because the reference implementation was very, very difficult to secure completely.”

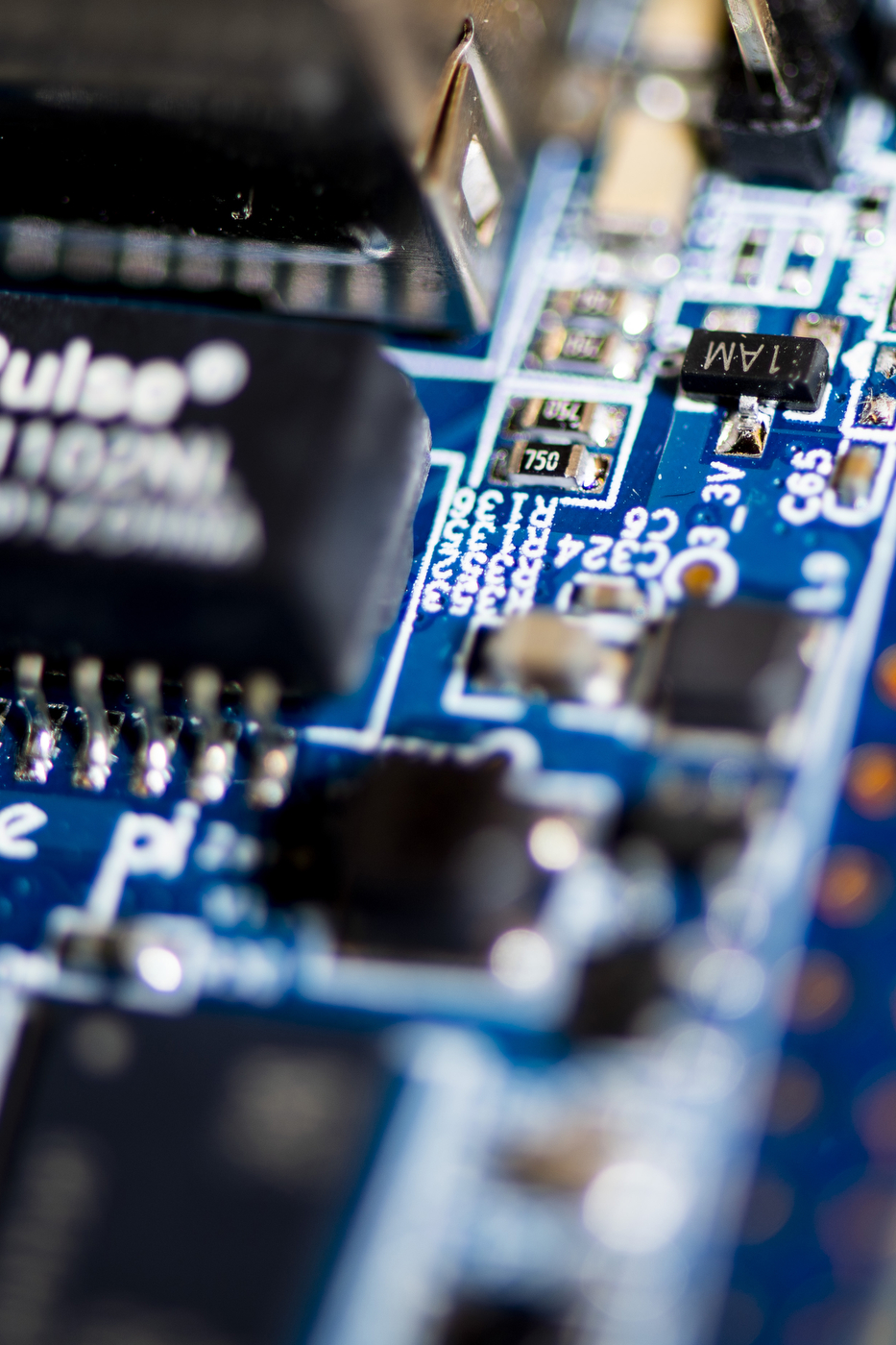

Noubir credits the students’ success to their use of several challenging cybersecurity techniques. In particular, the students designed a form of hardware memory encryption, which could keep attackers from being able to decipher any data they intercepted as it was sent to the system’s memory.

“It’s not easy to build something such that things get encrypted in the processor before they are written in the memory,” says Noubir. “It was quite impressive.”

As they found and patched holes in the security of their own system, the students took notes. When they moved on to the attack phase, they checked their competitors’ code for these same gaps. And in many cases, they found them.

“As a defender, you have to solve every problem. To win the game, you need to close everything,” Giese says. “As an attacker, you only have to poke a hole somewhere in this whole system. It’s a very asymmetric thing.”

The team intends to use the prize money to help fund a trip to DEF CON, an annual hacker conference in Las Vegas. Giese says members of the team also hope to start a new cybersecurity club on campus to help a wider range of students learn about and get involved in hands-on competitions like this one.

“It’s not only for people who study cybersecurity,” Giese says. “Developers and product designers need to have an understanding of what kind of shady things can happen. Because if you make a single mistake, then you’re done.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.