We’ve lost something important in the age of screens. 3D printers can bring it back.

It was a long-running tradition in the 19th and 20th centuries. Cigar factories in Florida would bring in a reader, or lector, to read the news aloud to workers as they plied their meticulous craft.

The closest thing we have now to the oral tradition of reading are podcasts and storytime in school, says Sari Altschuler, an assistant professor of English at Northeastern.

She argues that the mass digitization of books, magazines, and other print materials has transformed our relationship with texts. We miss out on the opportunity to learn through touch, she said, when we eschew paper books and other print forms for electronic books that can be read on digital devices.

“People tend to think about reading as a visual activity even though they’re processing it through a variety of senses,” she says. “But we learn through multiple senses, not just the visual.”

Altschuler thinks a lot about how to restore the tactile experience of reading a paper book and flipping through its pages. Touch screens mimic the experience of physically handling a book, she said, but fall short of the real thing. Still, these features remind us of how important touch is to learning.

Now Altschuler is part of a collaboration that has launched a new interactive exhibit to celebrate the multisensory experiences of reading.

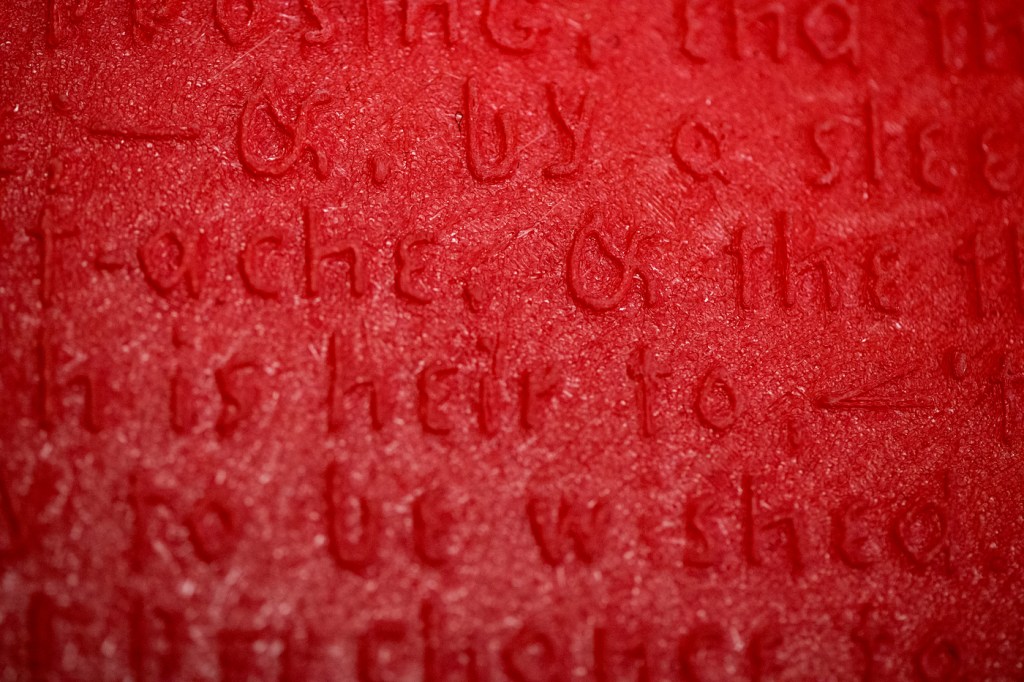

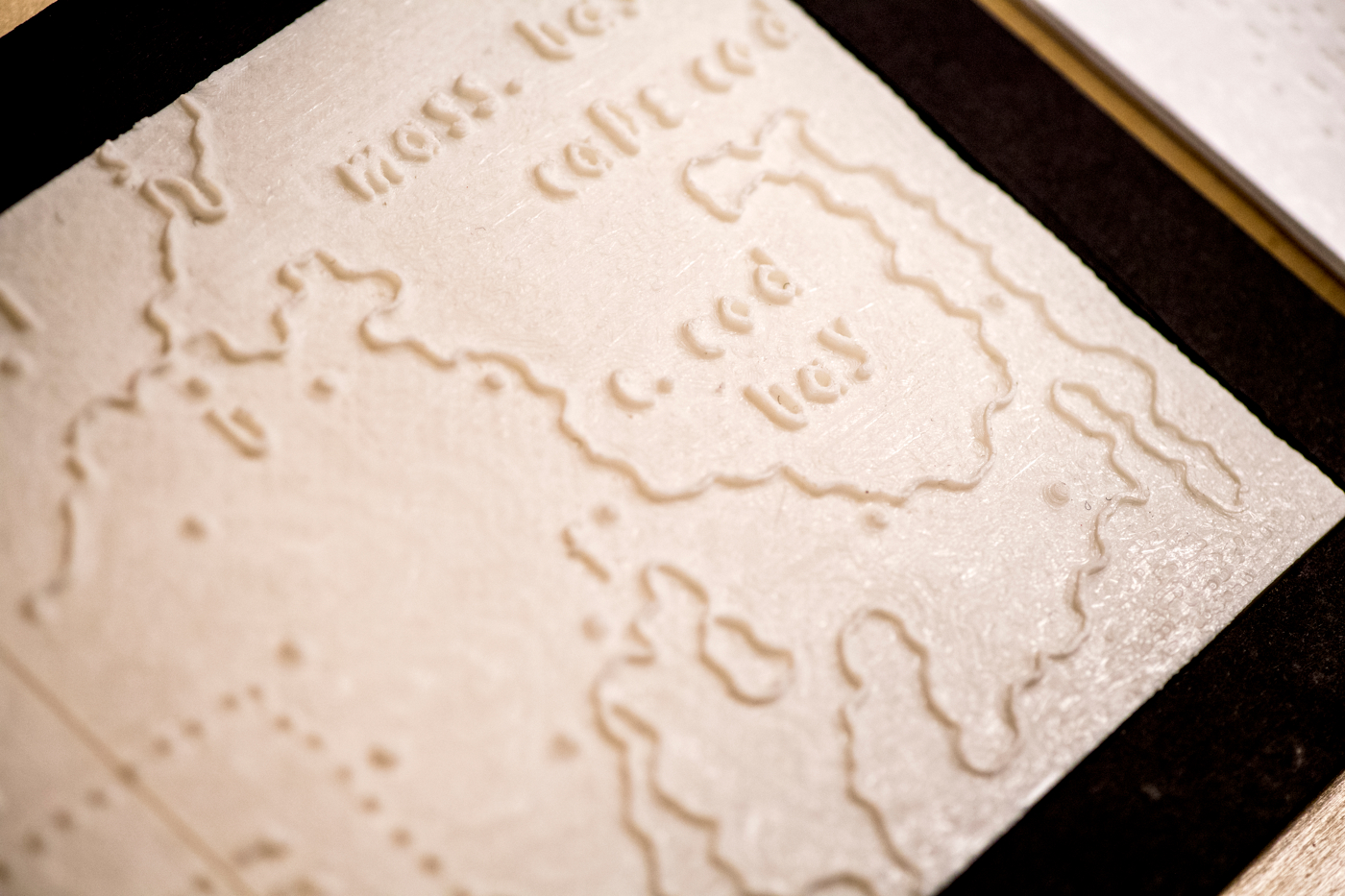

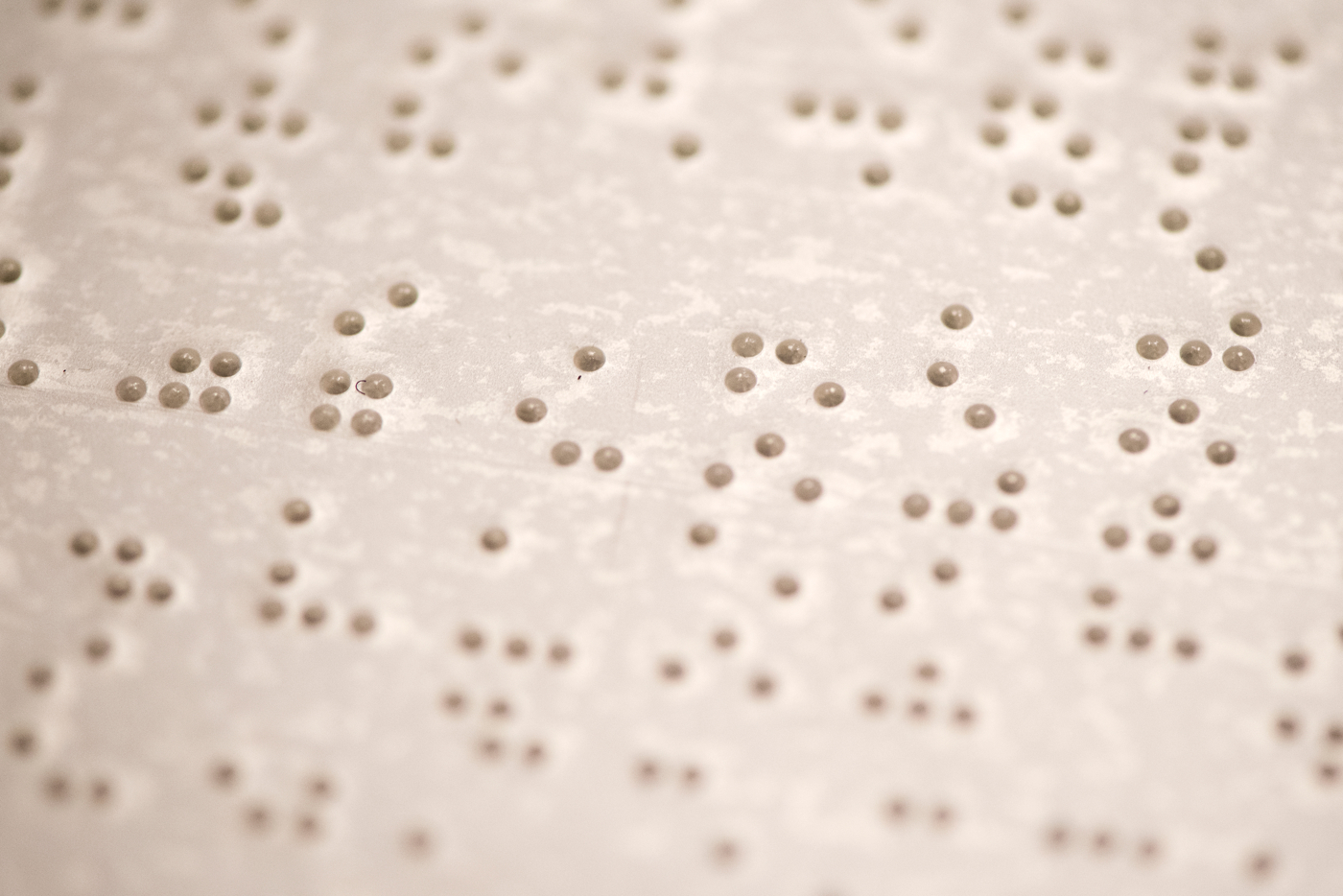

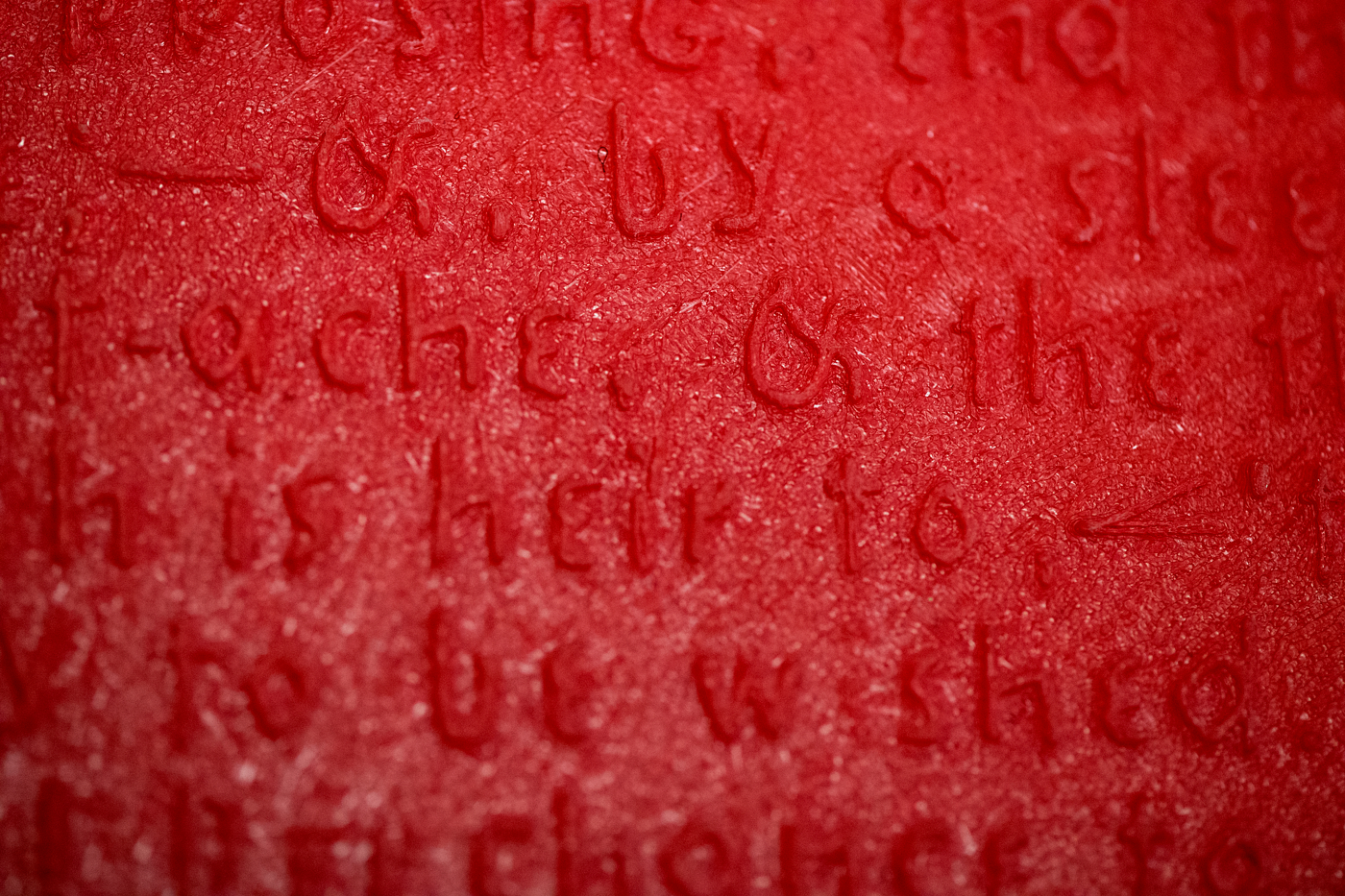

The exhibit, titled “Touch This Page! Making Sense of the Ways We Read,” showcases 3D-printed replicas of early 19th and 20th century texts designed for readers who are visually impaired, in an effort to show how touch, sight, and sound contribute to reading. Altschuler hopes visitors will also learn a thing or two about the history of disability and the daily experiences that face people who are visually impaired.

“We’re hoping people will think differently about technology and the intersection between the digital and the tactile,” says Altschuler. She created the exhibit in collaboration with Waleed Meleis, associate chair and associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern, Dan Cohen, vice provost for information collaboration and dean of libraries at Northeastern, and David Weimer, the librarian for Cartographic Collections and Learning at the Harvard Map Collection. Together they formed a partnership with the Perkins School for the Blind to develop “Touch This Page!”

Sari Altschuler, Dan Cohen, and Waleed Meleis.

The objects for the exhibit were created by five Northeastern undergraduates who design and build devices to improve the lives of people with cognitive and physical disabilities as members of the Enabling Engineering student group on campus. In addition to technical expertise, the group, comprised of members Nicolas Fong, Akira Watanabe, Julian Slade, David Ewen, and Jack Cardin, provided funding, equipment, and other resources to bring the objects to life.

Watanabe, a fourth year computer science and biology student, said that working on the exhibit gave him a better appreciation for the artifacts of the past and how much technology has advanced.

“I think it’s cool that we can now use modern technology to replicate old artifacts, and show people the kind of things that people had to use in the past, which I think gives you a better appreciation than a digital screen would,” Watanabe says.

Meleis, who advises the students in the Enabling Engineering group, described the replication process as a laborious task that took more than a year.

“The students have really driven this project; they have been the technical experts,” Meleis says. “We’ve been developing this process, and really breaking new ground to develop these new techniques to faithfully replicate these very delicate, very old artifacts for the blind.”

Cohen helped to create the concept for the exhibit. He said that in doing so, he considered the nature of reading and how to convey the different formats in which it is available.

“It was really eye-opening for me to learn, especially from Sari, about the history of tactile writing systems like braille, and thinking about how to project those ideas to the broader Northeastern community,” he says.

Northeastern, the Harvard Library, the Perkins School for the Blind, and the Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center at the Boston Public Library will simultaneously host the exhibit until mid-April. The exhibit opened in the lobby of Northeastern’s Snell Library on Feb. 1.

In conjunction with this exhibit, Northeastern and Harvard plan to host a symposium in April for scholars, librarians, and researchers to discuss the accessibility of historical archives.

The goal of the project is to expand the exhibit nationwide to make it accessible to a broader range of audiences, Altschuler said.

Those unable to see the exhibit in person can do so online at touchthispage.com, which enables visitors to 3D print the objects on display.

Anyone interested in digging deeper into the exhibit is encouraged to listen to Northeastern Library’s “What’s New” podcast, which dedicates one episode to “Touch This Page!” and another to the work of the Enabling Engineering group.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.