Does having a gun at home really make you safer?

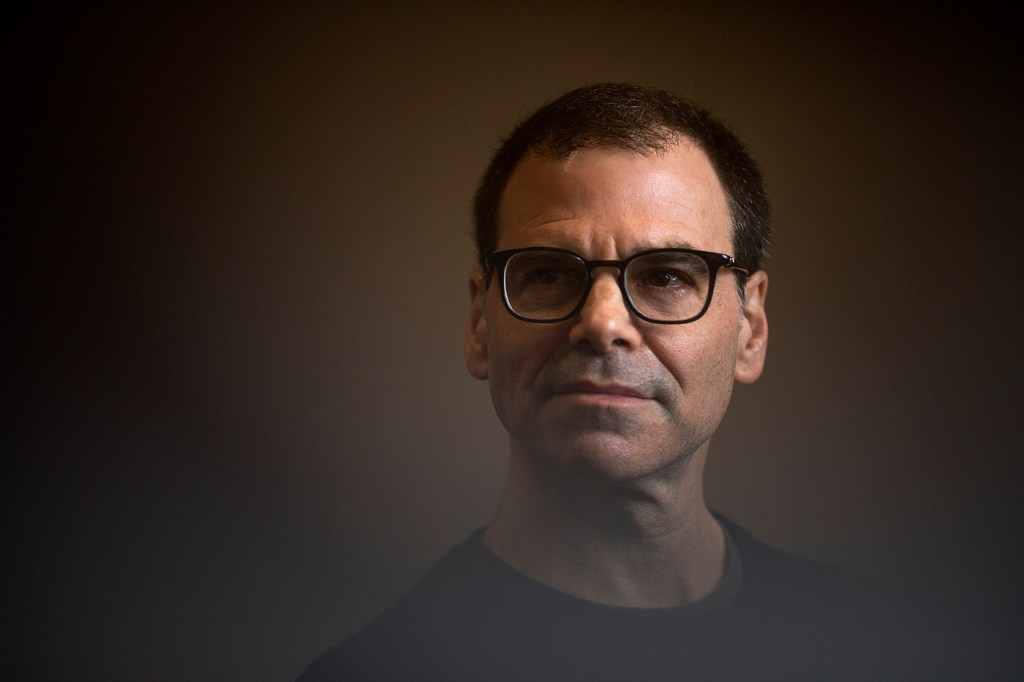

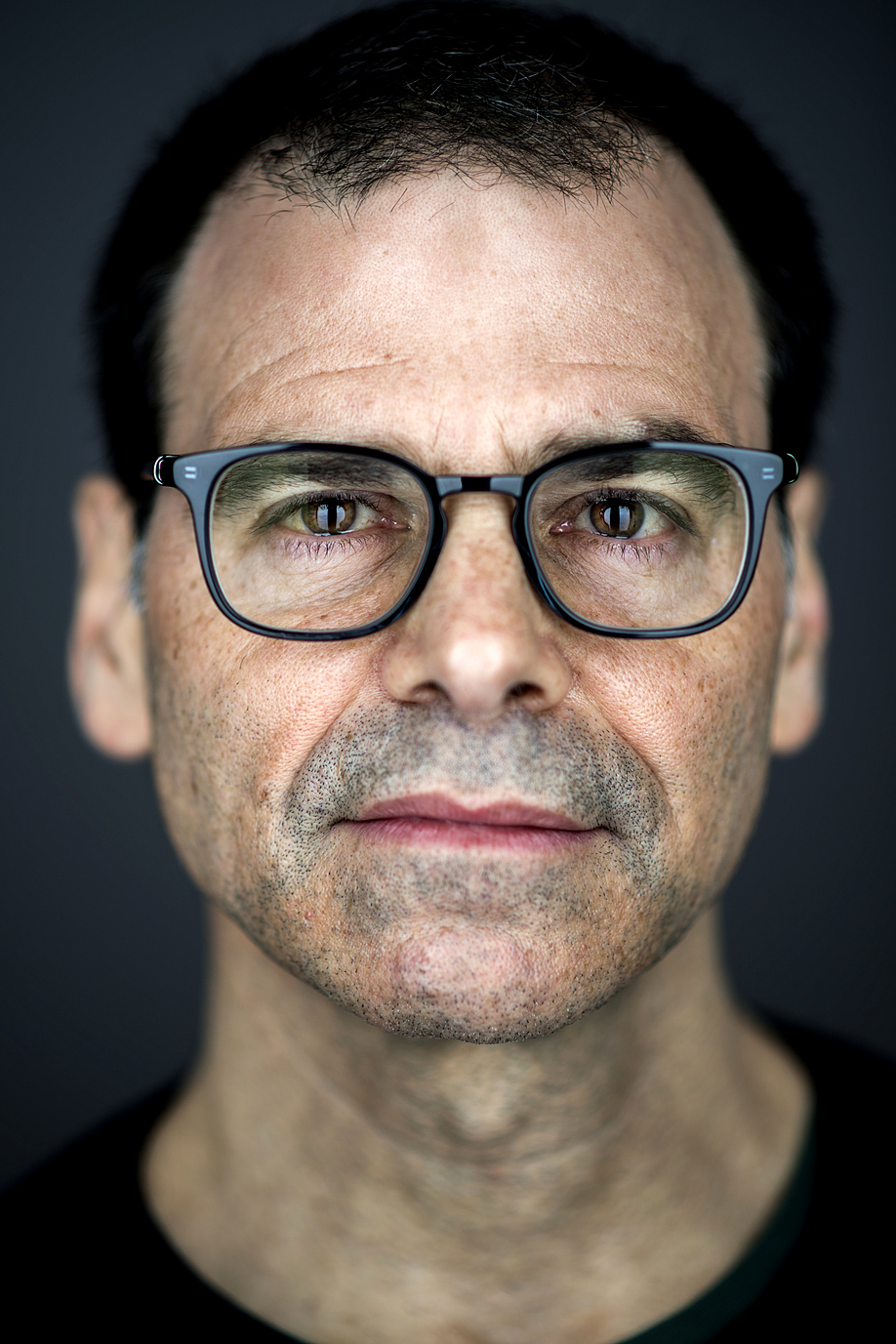

Keeping a gun in your home is supposed to keep you safe. Matthew Miller’s research suggests that the opposite is true.

“One-third of all households have guns, and I just don’t think people are aware of the risks that they’re assuming for themselves, or imposing on everyone else who lives in that home,” says Miller, a professor of health sciences and epidemiology at Northeastern. “I don’t think people have the information. I don’t think that they have internalized the risks.”

As one of the nation’s leading researchers of gun violence, Miller takes on the responsibility for piecing together that information. His work, which has revealed that people in households with guns face increased risk of injury, death, and suicide, is painstaking. He has co-authored recent studies that have found that Americans are generally unaware that access to guns increases the risk of suicide; and, further, that parents or caretakers tend to not recognize the need to make their guns inaccessible to children who are at risk of doing harm to themselves.

The findings have exposed Miller to the vitriol of America’s debate over gun control.

“I don’t spend any time worrying about that,” Miller says of the attacks that come his way. “I’m actually not on social media, so I don’t see the tweets or the Facebook posts.”

He is far more concerned with the dearth of government funding for his research. It explains why his community is so relatively small: Miller estimates that only a couple of dozen colleagues throughout the United States devote at least half of their research to gun violence.

“As opposed to the thousands who are looking at health insurance, or the delivery of medical health care, or infectious disease,” Miller says. “The number of people who die by motor vehicles every year is about the same as die by firearms. And 50 times as much money is spent on motor vehicle crash research—every year, federal funds—compared to funds spent on gun research.”

Almost 40,000 people were killed by guns in the United States in 2017, marking the third straight year that casualties had risen. And yet, despite the public health crisis that this represents, Miller finds himself warning young scholars before they follow his example.

“It’s not a field that I recommend to my graduate students, because it’s not going to have steady and sufficient funding streams,” Miller says. “And so anyone who wants to go into this area should go in with that in mind.”

Miller’s path to this line of research was itself complicated and painful. In his previous life, Miller was a rising physician at one of the world’s leading cancer centers. That he exchanged that life for this one is as illuminating as it is poignant.

‘Too emotionally difficult’

Miller graduated with degrees in biology and medicine from Yale. His career as a doctor was off to a strong start in the mid-1990s when he arrived at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. His professional trajectory was rising in sharp contradiction with the decline of his patients. Many of them had been unable to treat their cancer elsewhere. They came to Dana-Farber in search of live-saving miracles.

Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

“The Dana-Farber gets referrals from all around the world, and some of the people who are referred have exhausted the known, therapeutic options elsewhere,” Miller says. “They face daunting odds.”

Miller found the relationships with patients and their families weighing on him. He struggled with caring for patients for whom there was very little hope.

“I just felt that taking care of people who are dying of cancer, and their families as well, which is an important and noble undertaking, was too emotionally difficult,” Miller says. “It was hard to attend to the existential and emotional needs that my patients and their families had, and still have time to remain connected to the things in my life that were important to me. I was taking it home with me.”

He was having difficulty maintaining the crucial balance between their needs and his own needs.

“The patients and their families deserved to have someone who could be there 24/7,” Miller says.

In his move away from medicine, Miller found himself turning to public health research—with a focus on America’s most toxic subject of research.

Leaping head-first into the American gun debate was an opportunity to save lives without sacrificing his own. Miller returned to school. On weekends, he moonlighted in hospital emergency rooms to help pay his bills. He found his way.

Changing behaviors

As frustrating as it has been for Miller to see lawmakers refusing to institute gun reforms that are backed by a majority of Americans, he has also realized that congressional action alone cannot resolve the crisis.

“I think the biggest benefit that we’re going to see, in lives saved and injuries averted, is when the social norms change around what it means to be a responsible gun owner—of not taking on the risk of bringing guns into your home and storing them unsafely,” Miller says. “We’re not going to legislate our way out of a lot of those problems.”

Much of his work has focused on suicides by firearms, which Miller views, in many cases, as preventable deaths. In moments of desperate weakness, people kill themselves with guns that are accessible because they have not been locked away in the home. If the guns were not readily available, says Miller, the rate of death would drop.

“They would be better off if the gun were stored away from the home, or at the very least in a way that anyone at risk doesn’t have access to that gun,” Miller says.

Those who are forced to attempt suicide by another method, he says, would have a higher chance of surviving.

“When you take pills, or you cut yourself, fewer than two or three percent of those people die [by suicide],” Miller says.

Among those survivors, fewer than 10 percent will go on to die in a subsequent suicide attempt.

“Whereas the likelihood of death with a gun is 90-plus percent, with no chance to back out,” Miller says. “You pull the trigger, and usually you don’t get a second chance. So you can save lives by making it harder for people. You’re exchanging a 90 percent chance of dying for what is usually going to be a substantially lower risk.”

Miller is focused on supplying evidence that may change behaviors. He approaches his research from the perspective of someone who disrupted his own career path.

“My identity as a clinician was one of the things I had the most confidence in,” says Miller, who is also an adjunct professor of epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, and co-director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center. “Giving that up and starting again, from scratch, that was hard. Because there was a real void, and it was like, who am I?”

He understands that the struggle to reform the American relationship with guns will continue to be slow going.

“I don’t think human beings have all that much insight into why they do lots of things,” he says.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.