Can data help make racial profiling by police a thing of the past?

When Jack McDevitt was asked to lead a study to determine whether police officers in Kansas engage in racial profiling, he didn’t have to think twice.

McDevitt, who directs the Institute on Race and Justice at Northeastern, said similar studies he has conducted in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Seattle have resulted in improved relations between the local police departments and in some of the communities they serve.

Now he has agreed to develop a process for documenting traffic and pedestrian stops in Douglas County, Kansas, to determine if racial profiling exists in the county.

“Police departments can tell you incredible amounts of information about where they make arrests, who they arrest, where they get 911 calls from, but very few police departments collect information on who they conduct traffic stops on,” said McDevitt, who was asked to conduct the study by the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, a policy advisory group that’s based in Douglas County, Kansas, and comprised of academics, policymakers, law enforcement officers, and community groups. “It hasn’t been data driven the way much of the rest of policing has been done.”

An article in the Lawrence Journal-World, a daily newspaper in Kansas, mentions that the idea for the study was proposed by a former local police chief. The article also cites the disproportionate number of black inmates in the Douglas County Jail.

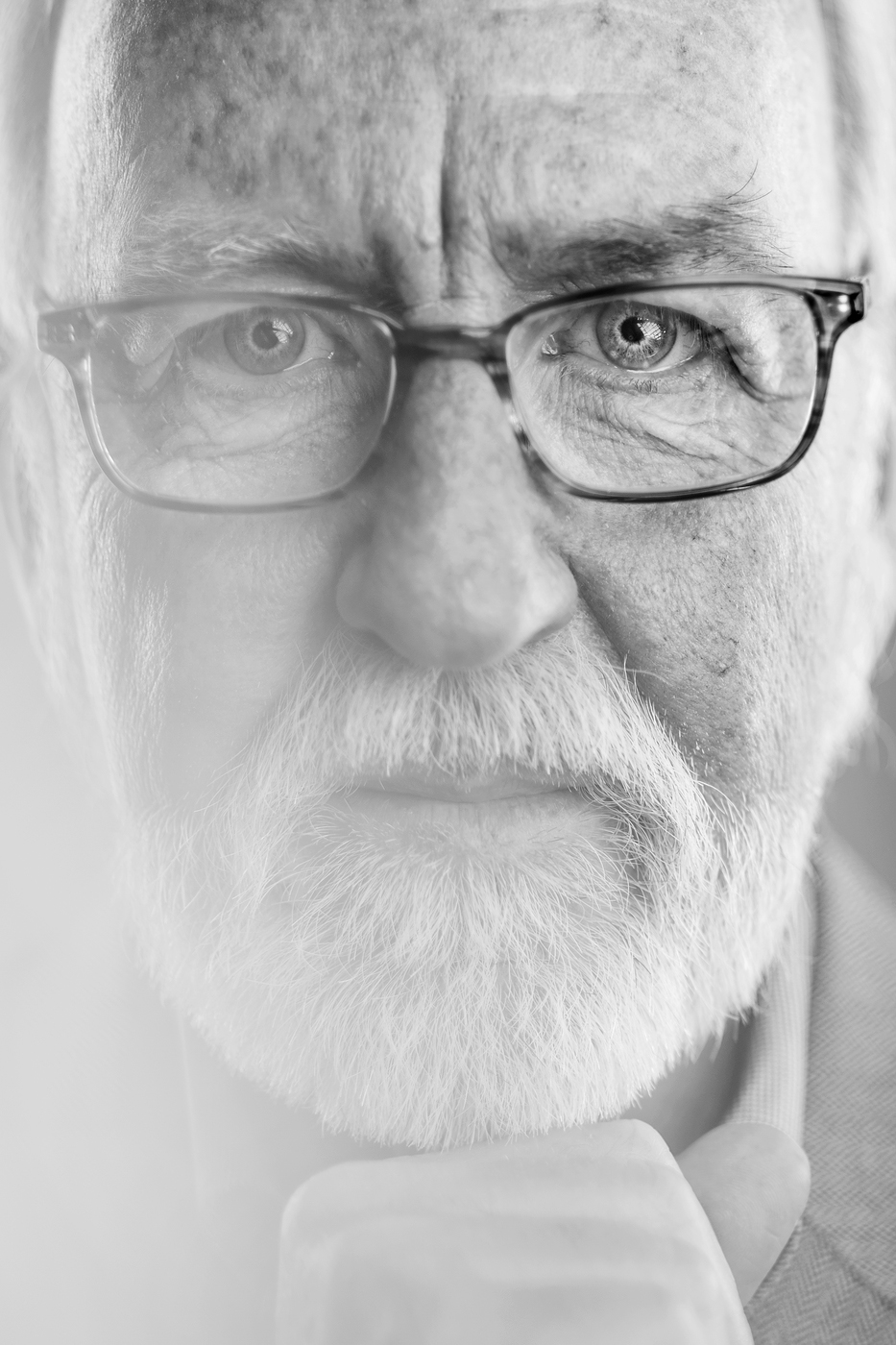

Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University

But McDevitt sees the study as a sign that Douglas County is taking preemptive action on the issue rather than trying to address an existing problem. He’s looking to change the way police departments collect data with the help of his colleagues, Amy Farrell, an associate director of criminology and criminal justice at Northeastern, and Janice Iwama, who graduated from Northeastern in 2016 and now teaches at American University.

The researchers will seek to find whether there are disparities in the racial breakdown of motorist and pedestrian stops in Douglas County, and if so, what’s causing them and whether it is systemic.

“Once you have the data you can say, ‘OK, it’s happening in this section or during this time period of the day,’” McDevitt said. “If you don’t have data, you just have to go by a complaint by a community member and you don’t know if it’s a pattern or one-off.”

The study launched in late December and will continue for the next two years with funding by Douglas County, the cities of Lawrence, Eudora, and Baldwin City, and the University of Kansas. Once it’s completed, Douglas County law enforcement agencies will have a data collection and analysis program in place for ongoing use.

“Most often these studies are funded through federal grants,” said McDevitt. “This time, the communities came together and said it was so important they’d pay for it themselves, which is pretty interesting and again speaks to why we wanted to work with them.”

Studies such as this one are important, said McDevitt, because they allow law enforcement agencies to monitor whether they’re enforcing the laws disproportionately against one community.

“I think these kinds of efforts by police departments are hugely important and send messages that the police want to get it right, they want to increase trust between the police and their communities,” he said.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.