Fighting wildfires is a dangerous job. These researchers have a plan to make it safer.

A firefighter rushing into the smoke-filled interior of a building wears a full face mask connected to a canister of breathable air. A firefighter battling wildfires in the western United States typically wears a bandanna.

The effects of smoke inhalation on firefighters who battle blazing buildings is well-studied. Specific regulations dictate what these firefighters should be wearing in different situations to stay safe. But there hasn’t been enough research to provide similar guidelines for wildland firefighters.

“There are some studies on acute effects—they can tell you what will happen immediately—but nothing really about what’s going to happen in the long term,” said Jessica Oakes, an assistant professor of bioengineering at Northeastern. “We’re going to fill that gap.”

Oakes and fellow assistant professor Chiara Bellini recently received a $1.5 million grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency to study the health consequences of smoke inhalation on wildland firefighters and provide recommendations for protective equipment that will keep the firefighters safe.

“There are people that spend maybe 10 or 20 years of their youth out fighting these fires,” Oakes said. “Then they become middle-aged or senior adults and we would like to prevent them from having cardiopulmonary diseases.”

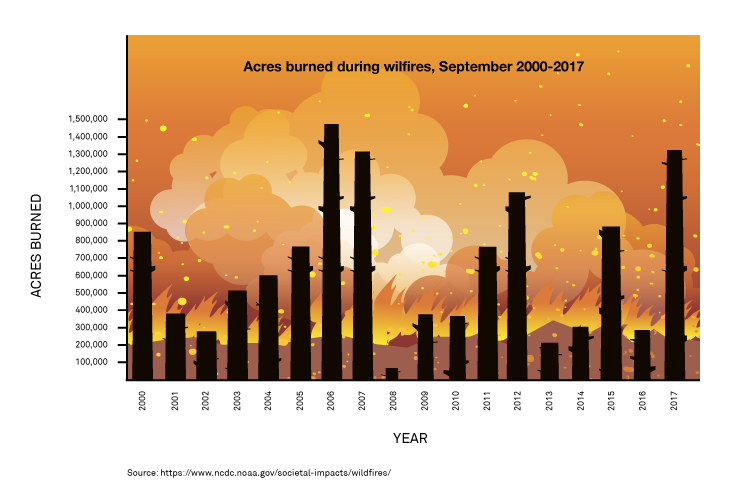

Since the 1980s, the number of large wildfires has been slowly increasing, and that is expected to continue. So far this year, wildfires have burned over eight million acres, an area roughly the size of Jersey.

Wildland firefighters often work 12-hour shifts, battling the same blaze for long stints. Sometimes firefighters are working to contain large out-of-control flames, and other times they’re creating smaller, controlled burns or following behind a fire to put out the areas that are still smoldering.

“With the wildland fires, they’re out there at basecamp for weeks,” said Oakes. “It’s accumulated exposure that you worry about.”

Oakes and Bellini are working with an advisory panel of firefighters led by Casey Grant, the executive director of the Fire Protection Research Foundation, to ensure that their research meets the firefighters’ needs and to help share their findings. Their goal is to understand what protective gear firefighters use in different situations, and then determine the best ways for them to limit their cardiovascular and respiratory risks, Bellini said.

“We’re not going to tell them they have to wear a full respirator the entire time that they’re in the field,” Bellini said. “That’s just not realistic.”

The researchers plan to use computational models and animal models to determine what these firefighters are being exposed to and the best equipment to protect them. But if you’re going to study smoke in the lab, you need a fire expert.

For that, Oakes turned to a friend from graduate school, Michael Gollner, who is now an associate professor in the Department of Fire Engineering at the University of Maryland.

“He’s going to be building our fire,” Oakes said. “It has to burn for a long time and be able to constantly add fuel. If anyone can do it, he can.”

Gollner will design a smoke generator to match the chemical composition of a wildfire and do some of the preliminary testing on the protective equipment. Then he’ll send the generator for Oakes and Bellini to use at Northeastern.

“Because we’re coming from a bioengineering perspective, we can bring an understanding of the biomechanics as well as the modeling,” Oakes said. “We’re uniquely positioned to address this problem.”

They hope their work can help keep wildland firefighters safe.

“We’re trying to give the firefighters guidelines on how to protect themselves,” Bellini said. “To help the people who protect us to protect themselves long-term.”