These schoolchildren dreaded reading. Then they found the buried treasure.

“We finally found the treasure this week,” exclaimed Sebastian Beattie, an eight-year-old boy who will enter third grade this fall.

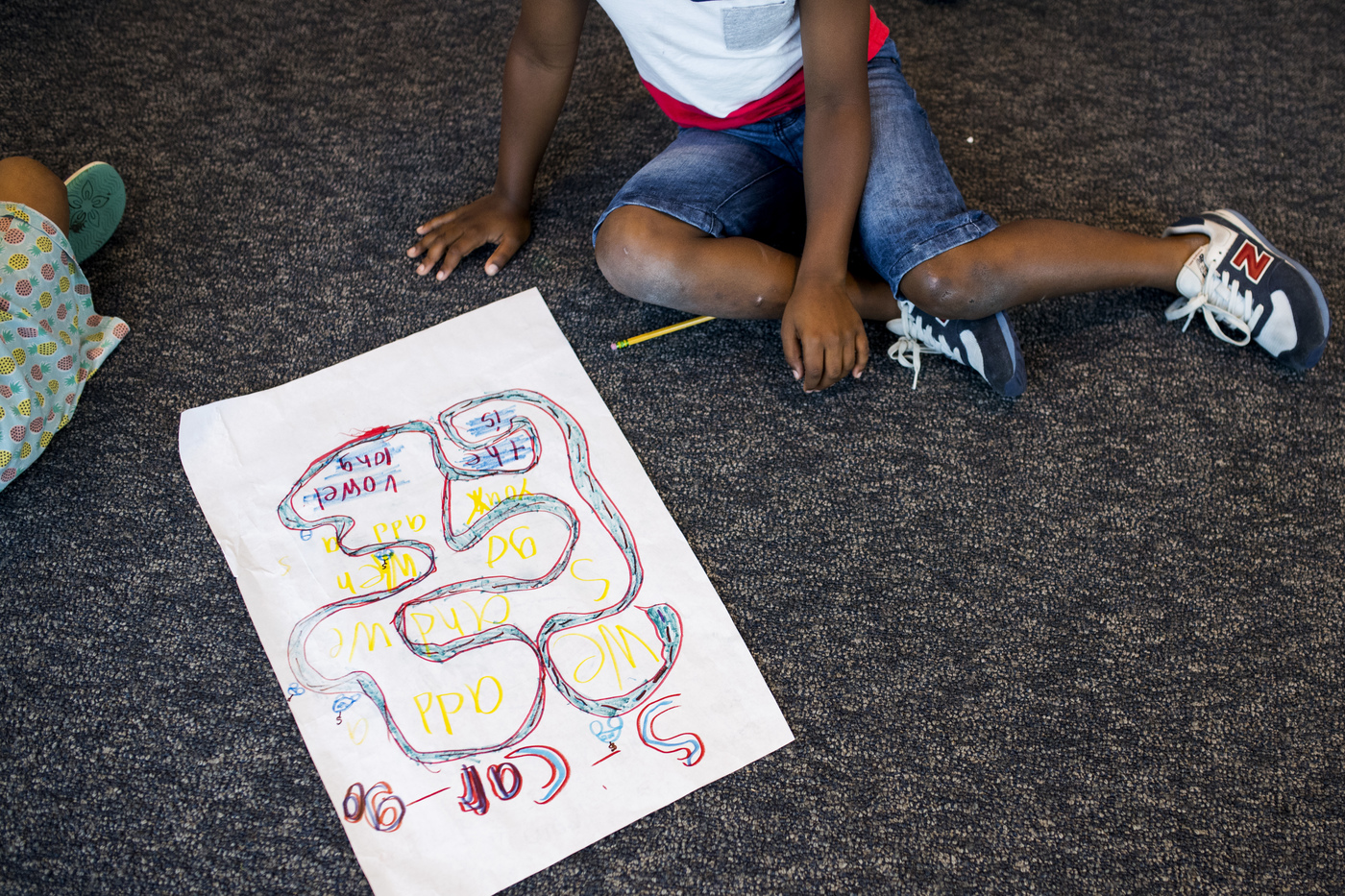

He was deciphering clues from handwritten letters and maps to locate buried treasure that a fictional band of pirates had stolen as part of a monthlong reading camp for children hosted by Northeastern last month.

Word Detectives, run by faculty and graduate students in Northeastern’s Speech-Language and Hearing Center, helped more than two-dozen elementary school children from Greater Boston improve their literacy skills with intensive phonics lessons and reading workshops.

“There’s a great need in the Boston area for these kinds of services,” said Sarah Young-Hong, the clinic director of speech and language services at the Speech-Language and Hearing Center.

Young-Hong, who helped to bring Word Detectives to Northeastern this year, said that the program targets the needs of participants by providing them a “blend of reading instruction and language-based teaching.”

The children in the program learned to read by breaking down words one sound at a time by using two different techniques—the RAVE-O reading intervention and Wilson Reading Training.

Mispronouncing a word was simply a “beautiful oops,” which helped to normalize mistakes, according to Elyssa Brand, the co-director of the reading camp. She said that the program built confidence in the students, who were constantly “growing their reading muscles.”

Laura McBride, one of six graduate students in speech language pathology who helped to tutor the students, said she learned just as much as her pupils.

“We completed training on teaching RAVE-O, but it’s so different from when you actually get in the classroom to teach the kids,” she said. “The questions they ask really get you thinking and test your knowledge.”

McBride said the students made “impressively measurable differences with their reading” with just one month of instruction. “Students who once looked like they were going to cry while reading started to come to camp excited to read chapter books,” she said.