China’s control of rare earth metals is a big advantage in a trade war. Northeastern researchers are trying to level the field.

This is part two of a two-part series. Read part one: At risk in a trade war with China? The rare earth metals that make your smartphone (and your guided missile).

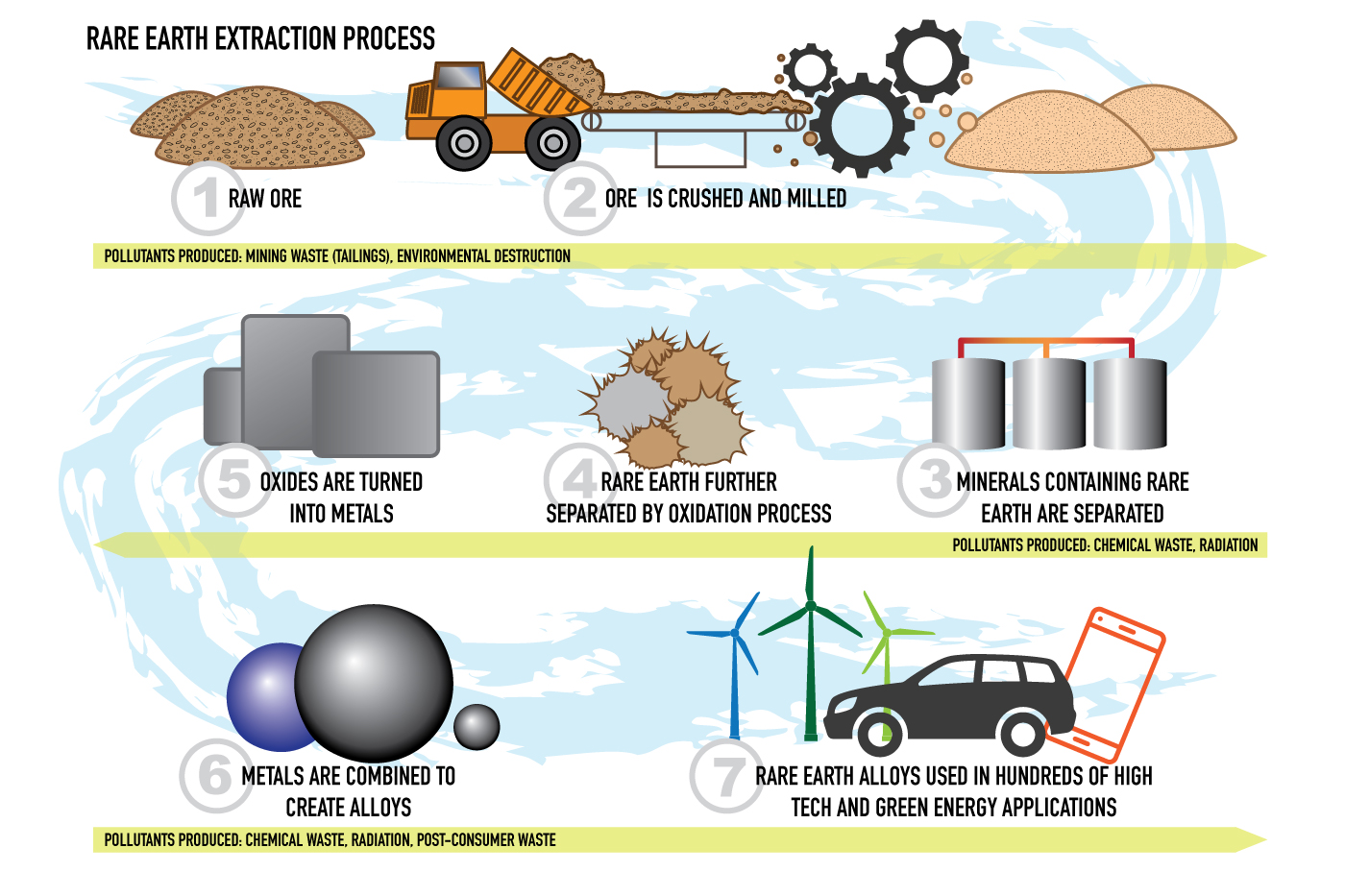

One potential effect of the escalating trade war with China is that Beijing could cut off America’s supply of rare earth metals, which are essential to the production of a vast range of products: smartphones, guided missiles, wind turbines, military radar, electric cars, computer hard drives, and much more.

Because China controls more than 80 percent of the world’s supply of these precious metals, it’s possible that a trade war could affect the production of many consumer, medical, and military products at the core of modern life.

Rare earth metals provide high-powered magnets used in computer hard drives, wind turbines, naval radar, MRI machines and more. Conventional magnets that don’t use rare earth metals have to be twice and big and twice as heavy to get the job done. This is an obvious liability, whether you are trying to build a light and powerful motor for an electric car or a tiny motor for a laptop.

Northeastern researchers are trying to reduce our dependence on China by inventing alternative supermagnets that do not require rare earth metals.

Reducing U.S. dependence

The United States lost is position as the world’s top producer of rare earth metals in early 1990s and stopped producing entirely in 1998, when the Mountain Pass Mine in California was closed for a string of 60 toxic spills. It reopened briefly in 2002 but was quickly driven under by Chinese competition and declared bankruptcy in 2015.

I believe our approach to independence requires a diverse portfolio

Laura H. Lewis, Ph.D., University Distinguished Professor of Chemical Engineering

Although efforts are underway to reopen the mine under new ownership, the ore would still have to be shipped to China for processing. China remains the only nation with the ability to separate large quantities of rare earth processing from the raw ore.

There is no single way to eliminate U.S. dependence on Chinese rare earths, said Laura Lewis, a University Distinguished Professor of Chemical Engineering at Northeastern.

“I believe our approach to independence requires a diverse portfolio,” she said. “Just like in financial investing, we need to reduce our risk by using several strategies to improve our resiliency to disruption in the rare earth supply chain.”

One solution is to stockpile rare earth metals in case of a second Chinese embargo. Another idea is to develop ways to recycle rare earth metals from products such as used smartphones and computers. The recycling option, however, is currently so expensive and inefficient that it is not yet a viable choice.

Northeastern’s contribution

Lewis and electrical engineering professor Vincent Harris are working to develop alternatives to rare earth supermagnets, powerful magnets needed for military, consumer, and alternative energy applications.

Lewis has focused her research on creating more powerful magnets by changing the crystal structure of common metals such as iron and nickel.

“We know this can be done because highly magnetized iron and nickel alloys already exist in meteors,” she said. “But we don’t have billions of years, so we are working on the nanoscale to speed up the process in the laboratory. We don’t have a magnet yet, but we have some promising results.”

Harris’s work on supermagnets has been funded by several large grants from the Department of Defense and focuses primarily on military applications. He said the physics of magnetism is such that alternative magnets will never be more than 60 percent as powerful as their rare earth counterparts.

“So with these new magnets, you will have a secure supply chain, but the magnets will have to be twice as large to deliver the same performance,” said Harris, a University Distinguished Professor of Engineering at Northeastern who also has a joint faculty appointment at the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China.

He noted that the magnets in a 3.5-megawatt wind turbine require more than a ton of rare earth components, so redesigning turbines for non-rare earth magnets that are twice the size will be an expensive endeavor.

Harris said the Chinese have already announced their intention to dominate wind energy, based, in part, on their control of rare earth metals.

This is why Harris and others are working on the second half of the alternative magnet strategy—reengineering products so that they don’t require a magnet as strong.

In 2008, Harris founded Metamagnetics, which produces essential components for advanced radar and communication devices used on warships and military aircraft that do not rely on rare earth elements.

Harris said that Raytheon, Northrop Grumman, and Lockheed Martin are incorporating the company’s innovations into their defense, communication, and aeronautical products. With some modifications, Harris said the technology can be adapted elsewhere.

“The magnet technology for a Navy destroyer’s radar is quite similar to the technology in a cellphone base station or the GPS system on a satellite,” he said.

Harris emphasizes that reengineering a product can be expensive and that many private industries are not willing to make the investment.

“When we go to Tesla and say we can give them a reliable supply chain, but their motor will have to be twice as large, they won’t go for it,” he said. “They’ll take their chances with maintaining the Chinese supply chain, because with bigger magnets, the car is going to be heavier and the performance won’t be as great.”

Lewis agrees that physics and economics conspire against eliminating the world’s dependence on rare earth materials anytime soon. But Harris says it’s also telling that China tried to buy Metamagnetics several years ago, possibly to quash promising research into alternatives.

From the perspective of Ravi Ramamurti, a University Distinguished Professor of International Business and Strategy at Northeastern, the difficulty of replacing the supply stream for rare earth metals is why the threat of a trade war is so troubling.

“In an interdependent world, a trade war can only work if you can hurt another nation without hurting yourself,” he said. “This is why trade wars aren’t supposed to happen. They create a case of mutual hostage taking.”

Read part one of this two-part series: At risk in a trade war with China? The rare earth metals that make your smartphone (and your guided missile).