At risk in a trade war with China? The rare earth metals that make your smartphone (and your guided missile).

This is part one of a two-part series on rare earth metals.

As the United States inches closer to a trade war with China, it’s worth considering one of the aces China holds in this high-stakes poker game—rare earth metals.

Rare earth metals are essential ingredients in a vast array of consumer, medical, and military products ranging from smartphones to guided missiles. The list includes MRI machines, camera lenses, hard drives, speakers, wind turbines, televisions, naval radar, headphones, lasers, drones, night vision goggles, microwaves, telescopes, electric cars, the Mars Rover, and motors of virtually any kind.

And China produces more than 80 percent of the world’s supply of rare earth metals, according to statistics compiled by the United States Geological Survey.

The United States, in contrast, produces zero.

Countries that mine rare earths in 2017

“This is a leverage point for China,” said University Distinguished Professor of International Business and Strategy Ravi Ramamurti, an expert in emerging markets. “President Trump says he holds all the cards, but China’s monopoly on rare earths is one of the aces.”

And demand is rising. The United States’ imports of rare earth metals increased 27 percent from 2016 to 2017, according to the USGS, and maintaining that supply has been become a matter of national security, according to 2017 testimony by Sen. Lisa Murkowski, chair of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

A trade war could prompt China to cut off supplies of rare earth metals to American manufacturers. President Trump has already dragged rare earth elements into the conflict by including them on a list of proposed tariffs announced earlier this month.

The tariffs reflect Trump’s stated goal, signed into an executive order last December, to reduce the country’s dependence on foreign sources for “critical minerals,” and therefore the diminish the risk of disruptions in the supply of materials vital for manufacturers. But efforts to find a new supply of rare earth metals, or devise technologies that supplant the need for them, are still in the early stages.

China has not overtly threatened to retaliate in a trade war by limiting the supply of rare earth metals. But it has already demonstrated its ability to do so in the past. In 2010, the Chinese slapped strict quotas on rare earth exports, throwing the world economy into a panic. Prices skyrocketed four-fold in 2010, and then doubled again in the first four months of 2011. For some rare earth metals, the price increased nearly 700 percent in less than two years.

“It was a warning shot. They put the squeeze on to show what they can do, and then they open the supply valve again,” said University Distinguished Professor of Engineering Vincent Harris, whose research is focused on finding alternatives to rare earth metals for military radar and communications.

In this photo from 2010, workers use machinery to dig at a rare earth mine in Baiyunebo mining district of Baotou in north China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. (AP Photo)

When China opened that supply valve, prices dropped to 2009 levels in a matter of months. They had made their point loud and clear: As former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping said in 1992, “The Middle East has its oil, we have rare earth.”

What are rare earth metals?

“If you look at the periodic table and notice the two rows of 17 elements that stick out at the bottom like they don’t belong, those are the rare earths,” said Harris. Ten of those elements are essential to a range of modern products, whether it’s the compact, yet powerful magnets in naval radar systems or the coatings on fine lenses for telescopes, cameras, microscopes, and smartphone screens.

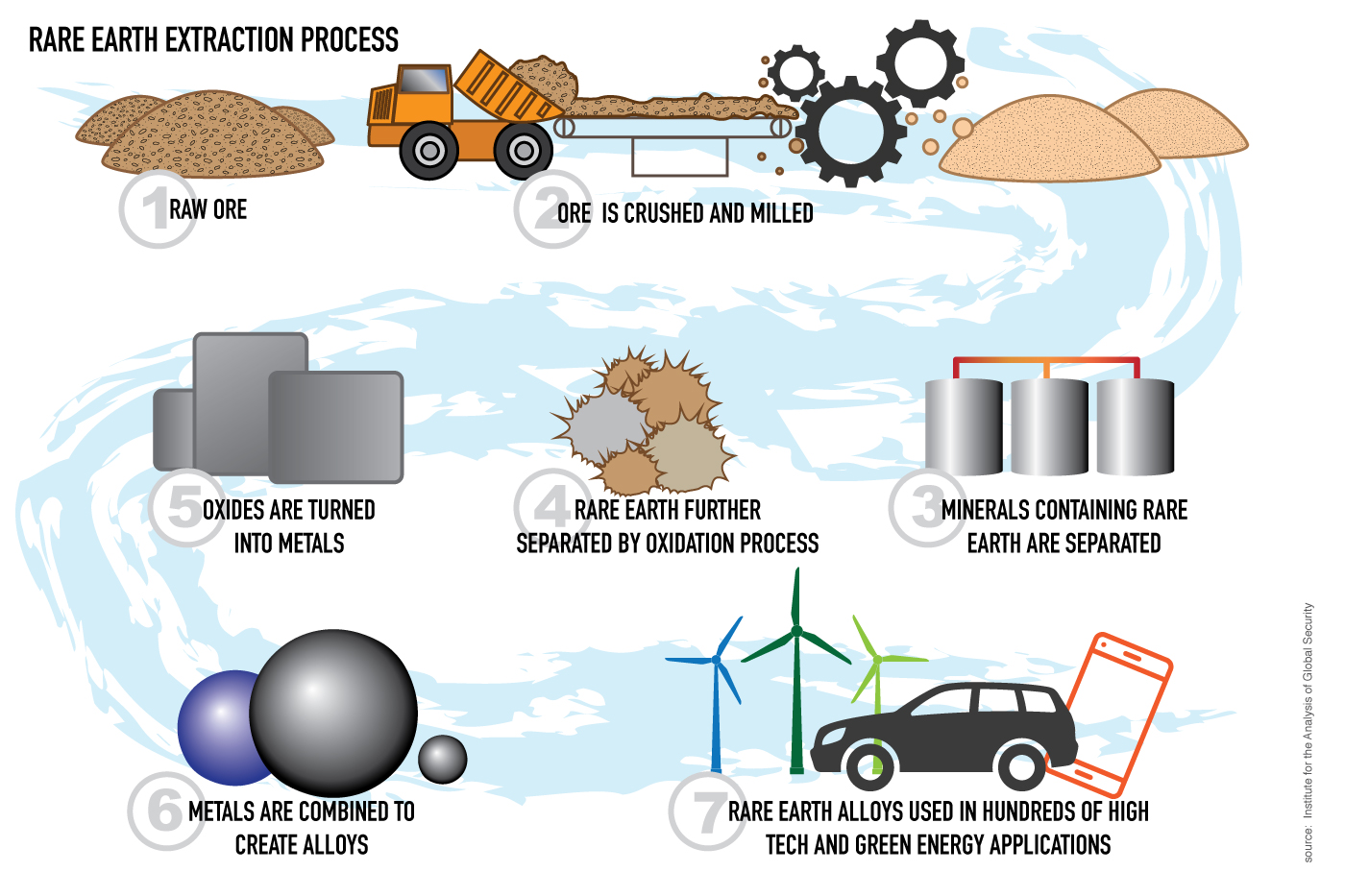

Despite their name, rare earth metals are not rare. They are scattered widely around the world. Their scarcity for human use is based on two factors: Their low saturation in the earth and the difficulty of separating the metal from the surrounding ore. That process can easily create an environmental disaster.

Source: Institute for the Analysis of Global Security. Infographic by Greg Grinnell

Open-pit strip mines scour the landscape, while extracting the metals from the ore requires highly toxic acids and temperatures of more than 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The process also releases radioactive waste into the water and air. The world’s largest rare earth operation, in Baotou, China, creates a toxic stew that is pumped into a man-made sludge lake adjacent to the mine in Inner Mongolia. Processing the ore into usable metals creates 2,000 tons of toxic waste for each ton of rare earth metals, according to The Guardian.

“You can reduce the environmental impact of processing rare earths, but you have to spend a lot more money,” said Harris, a regular visitor to the rare earth research facility in Baotou, China.

China’s market dominance

Although the United States no longer mines rare earth metals, it was once the world leader. That was due largely to the dominance of the Mountain Pass Mine on the edge of the Mojave Desert in southern California.

But the mine was closed in 1998 after a series of 60 toxic spills over the previous 14 years released 600,000 gallons of radioactive fluid into the desert. At the same time, China was on an all-out push to dominate the market.

“In the 1990s, the Chinese flooded the market with cheap rare earths and then, when they drove the competition out of business, they jacked up the prices and started buying up the competition,” said Harris. “This has been a slow, methodical process for the Chinese to create a rare earth monopoly.”

Top 10 countries that mine rare earths

There is another part to this story that goes beyond China’s aggressive trade practices, according to Laura Lewis, a University Distinguished Professor of Engineering who, like Harris, is working to develop alternatives to rare earth materials.

She explained that in addition to abundant natural resources and lax environmental regulations, China has invested heavily in mining and processing technology while benefiting from the world’s largest supply of cheap labor.

Ramamurti agrees, saying the key to China’s market dominance is the complete economic ecosystem it has built around rare earth metals.

“Reducing our dependence on China does not involve a single product or resource, so you can’t simply buy it somewhere else,” he said. “They monopolize the whole ecosystem of supply, production, and workers. To move elsewhere you would have to replicate that entire ecosystem.”