Unpacking the debate over person-first vs. identity-first language in the autism community

The question of how we define ourselves, and others, is a complicated subject for anyone.

But for those who have autism, or study it, the question is even trickier.

That’s because there is a fundamental disagreement over this: Should we say that someone is autistic? Or that they have autism?

Two stories recently published by News@Northeastern stirred up the debate. The first, about an activist named Lydia Brown, described Brown as “autistic.” The second was about an algorithm created by a Northeastern professor that can predict behavior in autistic children.

https://twitter.com/PastelVolcano/status/996826511037681665

In both cases, we used identity-first language (“autistic person”), rather than person-first language (“a person with autism”), because in each story, identity-first language was preferred by the subjects in the story. We’ll continue to do so in this story.

But that choice of words proved objectionable to members of the broader community of people who are affected by autism in some way, whether as family members or professionals in a disability field.

“Generally, it’s the people themselves who prefer to be called ‘autistic people’ and caregivers and professionals who prefer ‘people with autism,’” said Laura Dudley, an assistant clinical professor at Northeastern with more than 20 years of experience in developing and implementing programs for children with autism and related disabilities.

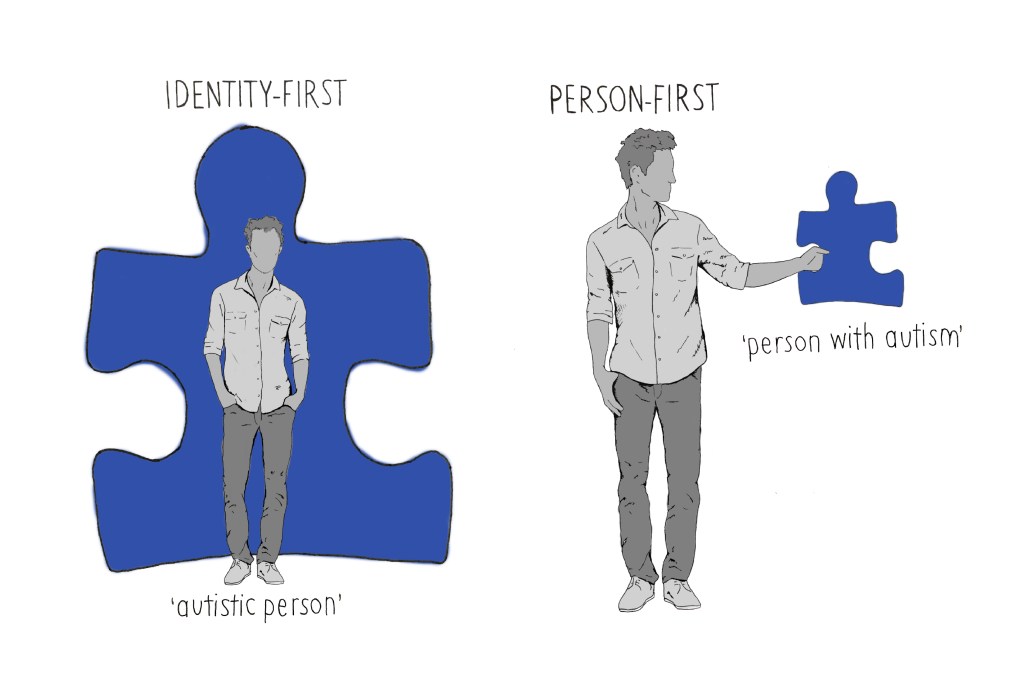

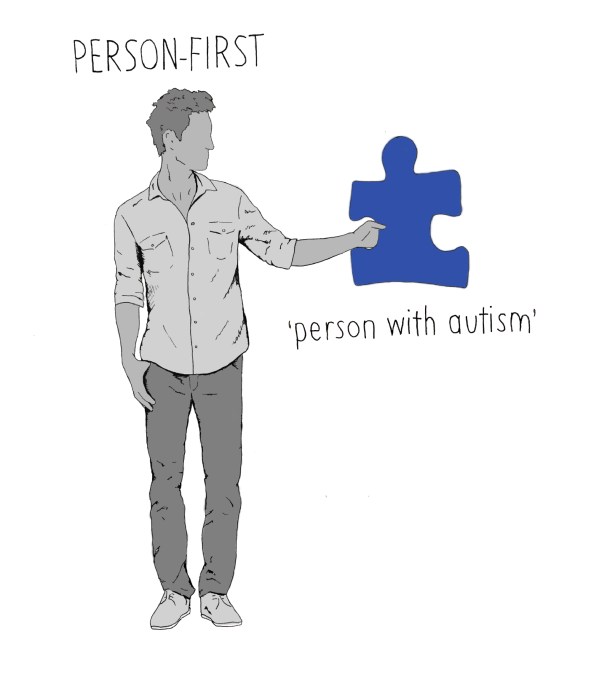

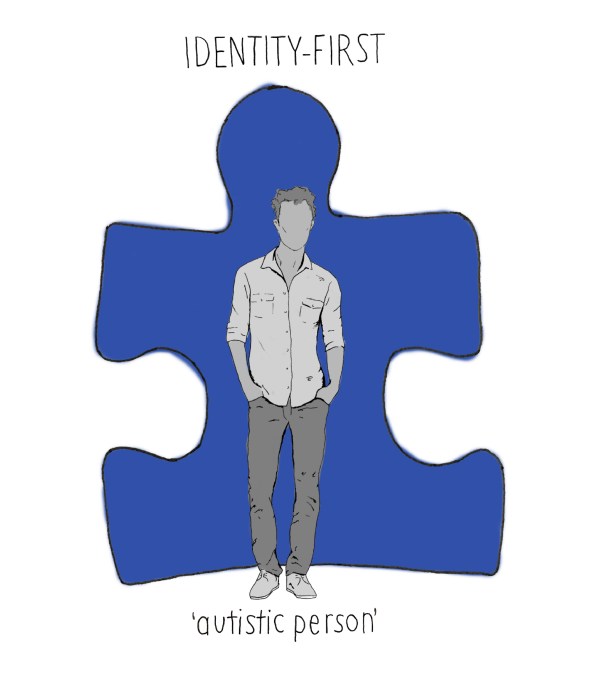

For people who prefer person-first language, the choice recognizes that a human is first and foremost a person: They have a disorder, but that disorder doesn’t define them. For people who prefer identity-first language, the choice is about empowerment. It says that autism isn’t something to be ashamed of.

For people who prefer person-first language, the choice recognizes that a human is first and foremost a person: They have a disorder, but that disorder doesn’t define them.

Illustration by Lia Petronio/Northeastern University

For people who prefer identity-first language, the choice is about empowerment. It says that autism isn’t something to be ashamed of.

Illustration by Lia Petronio/Northeastern University

“Both sides of the argument make sense to me,” Dudley said.

But it makes just as much sense that someone who has chosen one term is unwilling to accept the other.

“Language is a really powerful tool in society,” said Brown, an autistic person who was the subject of one of the earlier stories. “It shapes how we think about and understand our world and the people in it.”

Root of the split

As late as the 1980s, official medical records referred to people with intellectual disabilities as “morons,” “retards,” or “demented,” Brown said. The debate over how to describe autism stems from a reaction to this dehumanizing terminology by people with disabilities and the organizations that represented them, Brown said.

“When you’re referred to by one of these terms, it makes sense that you’d want to be seen as a person; to see the person first and then the disability,” Brown said. “The autistic, blind, or deaf communities, however, haven’t necessarily been affected at the same scale or scope as what happened to people with intellectual disabilities. In recent times, we haven’t been locked away en masse.”

Instead, Brown said, the preference for identity-first language in the autistic, blind, and deaf communities is born of “saying, ‘You need to respect and honor our identities, there’s nothing wrong with us.’ We’re proud to be autistic, proud to be deaf or blind.”

For someone like Dudley, however, a different history is foremost in mind. Dudley started working with the autism community in the mid-1990s, right after the federal Education for All Handicapped Children Act was renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. The federal change in terminology reflected a wider consideration for identifying language.

Because of this language change, and the broader cultural shift it represented, “For any professionals who started around that time, calling someone an autistic person doesn’t sound quite right,” Dudley said.

And while we might try to look to other communities grappling with identity and personhood, for example, Dudley said it’s the autism community that “seems to be the most passionate about this.”

When in doubt, ask

Brown and Dudley agree that it’s the members of a particular community who should control their preference for identifying language.

“Different communities of actually-disabled people or people with disabilities have different preferences,” Brown said. “But as with any group, especially any group of marginalized people, it’s the people who we’re talking about who should be dictating what they’re called. The same word that’s empowering for some people might be retraumatizing for others.”

Brown offers three rules of thumb for people unsure of which language to use.

“If you don’t know the preference of the person and don’t have a chance to ask them, go with the majority opinion of the community, because that’s a safe bet,” Brown said. “If you do have a chance to ask, ask and use that. And if you’re referring to a group of people who have different preferences, use the language of the majority of the group.”

For Brown, the worst thing a person can do is willfully ignore a person or group’s preference; for Dudley, it’s to say language doesn’t matter.

At the heart of this debate and others like it “is a sincere effort to respect people,” Dudley said. “Everyone gets passionate about this because, at the core, people want these communities to be respected. The problem is that we just don’t all agree on how, yet.”