Segregation by race and socioeconomic status persists in US cities, new study finds

When’s the last time you visited a neighborhood where practically everyone was different from you?

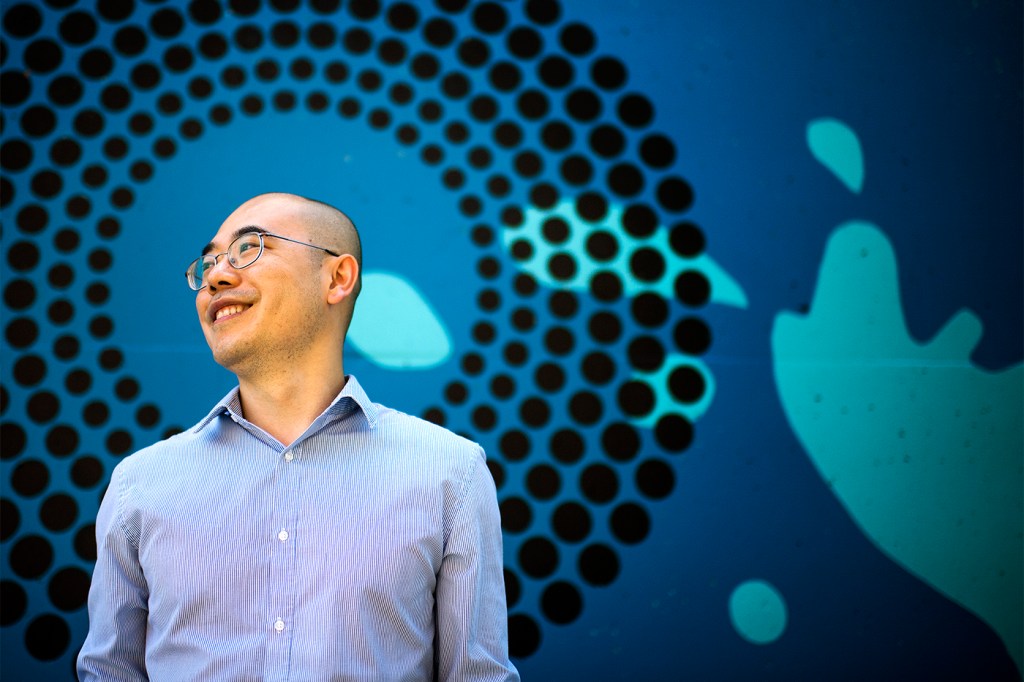

If you’re like most Americans—at least those who tweet—the answer is probably “rarely” or “never.” That’s because segregation by race and socioeconomic status in cities remains very much intact, according to new research by Northeastern professor Qi Ryan Wang.

Wang and his collaborators gathered and analyzed 650 million Twitter messages sent over 18 months. They studied about 400,000 residents living in the largest 50 cities in the United States. The tweets were geocoded, meaning they revealed the current geographic location of the user at the time of posting.

Researchers used the data to estimate users’ home locations and to understand their travel patterns. They found that residents of primarily black and Hispanic neighborhoods are far less likely to visit white middle-class neighborhoods than are residents of primarily white neighborhoods. This held true whether or not the black and Hispanic neighborhoods were lower-income, middle class, or wealthy.

Wang and his coauthors also found that people from lower-income white neighborhoods rarely travel to middle or upper-class white neighborhoods.

Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

Residents from all types of neighborhoods traveled about the same number of total miles throughout their cities. And they visited about the same number of individual neighborhoods. But those neighborhoods tended to look just like their own, in terms of the racial and socioeconomic makeup of residents.

The findings were consistent across all 50 cities, some of which have better public transportation systems than others. For example, the transit infrastructure of Boston or New York City is much more robust than that of Los Angeles, Wang said. Yet the trends identified in the study remained the same. This suggests that the lack of people visiting neighborhoods unlike their own has less to do with access to public transportation and more to do with social and cultural factors.

“Everyday leisure and work habits, visits to friend and kin networks—which themselves tend to be segregated—and a feeling of being comfortable or not in different kinds of neighborhoods by race and class all likely play an important role, based on what we know from smaller scale studies,” said Robert Sampson, professor of social sciences at Harvard University and a co-author on the study.

What are the consequences of social segregation? A large body of social science literature says there are many. For example, people lose out on job prospects, potential role models, and other valuable resources if they never travel to middle or upper-class white neighborhoods, which tend to receive more investment from a variety of sources.

“If young people are completely isolated from those neighborhoods, there is no chance they will access those resources,” said Wang, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering. “I think there is a larger question related to how we can reduce this kind of inequality and social isolation.”