The coldest rivers on Earth may hold clues about a warming globe

Flowing through frigid eastern Siberia, the Kolyma River is the largest river in the world that is completely underlain by frozen, icy soil called permafrost. Aron Stubbins traversed 15 time zones, making a pit stop in Yakutsk, Russia—one of the coldest cities in the world, with record temperatures of minus 84 degrees Fahrenheit—to reach the Kolyma. But the purpose of his frosty voyage was to study a process that could make the globe warmer.

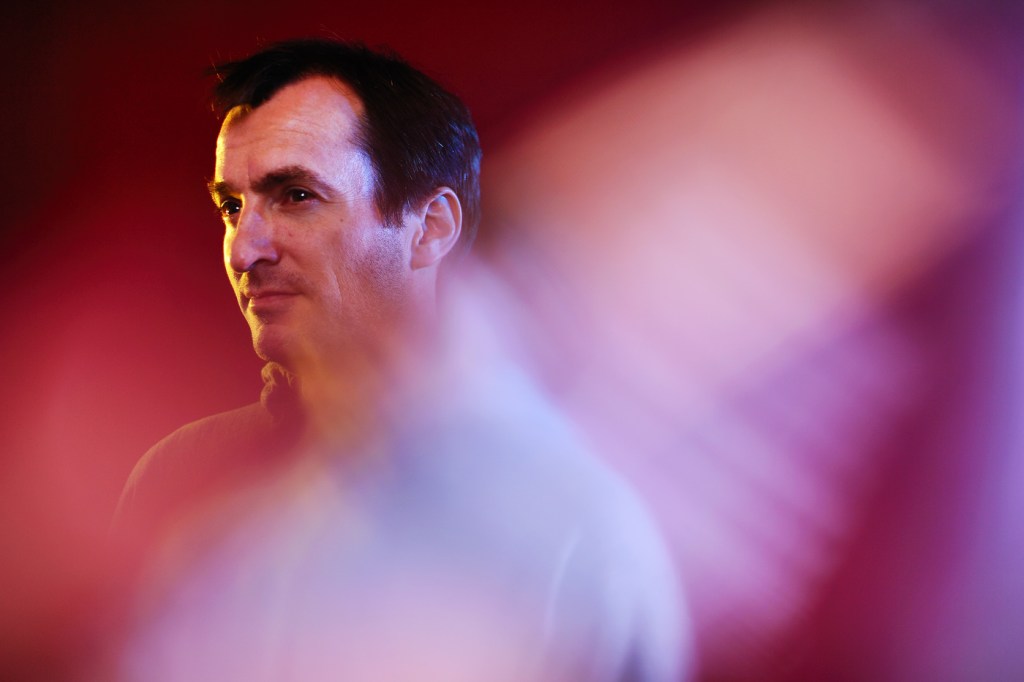

Stubbins, associate professor of marine and environmental sciences, joined Northeastern’s faculty in January after seven years at the University of Georgia’s Skidaway Institute of Oceanography. He now holds joint appointments with the College of Science and College of Engineering, and last year was named a fellow of the Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography.

Stubbins is an expert on dissolved organic carbon, which is the stuff left behind when plants and animals die. It’s what makes soil and rivers brown. And it has big implications for climate change.

Specifically, Stubbins studies how carbon moves off the land into rivers, where it eventually gets converted into carbon dioxide—a greenhouse gas that’s causing global warming. One particular area of concern is the carbon stored in Arctic permafrost.

The Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the planet. In fact, scientists estimate that 10 percent of the carbon stored in permafrost there could be released in the next century. That’s equivalent to about 1,50 Petograms of carbon—About the same amount that’s accumulated in the atmosphere since the industrial revolution, Stubbins explained. He studies what might happen if that defrosting and release of carbon takes place.

This research is what led him to the Kolyma River. Stubbins and his research team took samples of the streams created by melting ice near the river. Using radiocarbon dating, they found the carbon stored in the ice is about 20,000 years old.

“This old carbon has been frozen and locked away. It hasn’t had a chance to be degraded,” Stubbins said. “Like food in your freezer, it won’t go off as long as you keep it frozen. But we wanted to know what happens when you turn the freezer off and it gets into the water column of the Kolyma River.”

Stubbins took the samples from the ice streams and filtered them so all that remained was organic carbon. He then fed that ancient carbon to bacteria in water samples from the Kolyma River. The researchers found that after just two or three weeks, half the carbon was gobbled up.

“It’s been stored here and frozen away for 20,000 years,” Stubbins said, “but if it melts and manages to make its way to the river, more than half of it can be converted to carbon dioxide in a matter of weeks.” After that, he added, the carbon dioxide goes back into the atmosphere and could accelerate climate change.

Stubbins’ new lab at Northeastern’s Marine Science Center will continue this type of work. In one upcoming project, he is collaborating with Northeastern post-doctoral researcher Sasha Wagner to study black carbon—the char and soot left behind after a fire. Rivers carry dissolved black carbon to the ocean where it becomes stored for thousands of years. Wagner and Stubbins are teaming up to examine the exact source of black carbon in the ocean to better understand where it comes from and how it fits into the overall carbon cycle.

Stubbins said he’s happy to finally live in a place with hills for hiking. And he’s glad to still be by the ocean, where he can enjoy watersports like one of his favorite hobbies—bodyboarding.

“I’ve always lived close to the sea for a reason,” Stubbins said.