Engineering students flex their robotic muscles with hands, drones, and more

Northeastern engineering students showcased their robotics work last week at an expo in the Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Complex, giving attendees the opportunity to see a speedy flying drone, an autonomous kayak, and a prototype of a prosthetic hand in action. The expo was part of National Engineers Week at Northeastern.

Here, we explore a couple of those diverse robotics projects.

A bot for dynamic environments

Imagine a mobile robot in the home of an elderly person who could follow its owner around and be a “first responder” if the individual were to fall. That’s the vision of one project in Northeastern’s Robotics and Intelligent Vehicles Research Laboratory, or RIVeR Lab, directed by Taskin Padir, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering.

Padir uses a robot called the Turtlebot to train students taking his course on mobile robotics, as well as new researchers that join the lab. Turtlebots are relatively common and inexpensive robots, said Padir, who has 10 of them. One of the first assignments Padir’s students and new researchers learn is how to operate the robot and program it to navigate from one floor of a building to another. Once that task is complete, Turtlebot can be used to test and validate more complex algorithms.

Peter Dirksmeier, E’18, helped develop an algorithm that allows Turtlebot to follow a person around a room, which he demonstrated at the showcase. The robot uses a camera sensor to see and track distance points on an object, Dirksmeier said, which enables it to follow and avoid that object in motion. Others are working to program Turtlebot to navigate dynamic environments, such as a crowded metro station, Padir said.

The Turtlebot uses a camera sensor to see and track distance points on an object, which lets it follow and avoid that object in motion. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University

Mastering drones of all sizes

The Crazyflie 2.0 is aptly named. This compact drone—about the size of the palm of your hand—moves with impressive speed, zipping up from a table top to the ceiling in a matter of seconds.

Peter Downward, E’21, is working on co-op at the RIVeR Lab, where he is writing and testing code to make drones fly and navigate autonomously. Downward demonstrated how to control the Crazyflie using his cellphone, and explained that members of the RIVeR Lab use the drone to practice their flying technique. Once they’ve mastered control of the Crazyflie, researchers can try their hand at the DJI Matrice 600 Pro—a much larger and costlier drone.

“The Crazyflie is used by people who are working on the DJI as a learning platform, since it’s a smaller scale, more expendable, easier to replace, and cheaper alternative to the full-scale drone,” Downward said.

He added that the Crazyflie is programmable, allowing researchers to practice writing and executing code before programming the DJI Matrice 600 Pro. This is important, given the flying restrictions associated with the DJI, which is about a meter wide and much more powerful.

“We can fix any errors or mistakes with the code before testing it out on the full-scale drone,” Downward said.

Peter Downward, E’21, demonstrates how the Crazyflie 2.0 works. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University

A robotic kayak for dangerous waters

Also featured at the Robotics Showcase was JetYak, an autonomous vehicle that’s shaped like a kayak and includes a gas-powered engine. Hanumant Singh, professor of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern, has built more than a dozen JetYaks for researchers all around the world.

The autonomous vehicle is especially useful for exploring areas that are dangerous or difficult for humans to reach. For example, in July 2013, the autonomous vehicle was used to measure freshwater flow in front of glaciers in Greenland where icebergs are actively breaking away.

Scientists from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology have used the JetYak to examine zooplankton migration in the Arctic polar night. Larger vessels add to the light pollution zooplankton naturally hide from. But the JetYak does not, enabling researchers to observe the zooplankton’s natural behavior for the first time in a low-light climate.

The Jetyak is especially useful for exploring areas that are dangerous or difficult for humans to reach, such as the Arctic Ocean. Photo courtesy of Hanumant Singh.

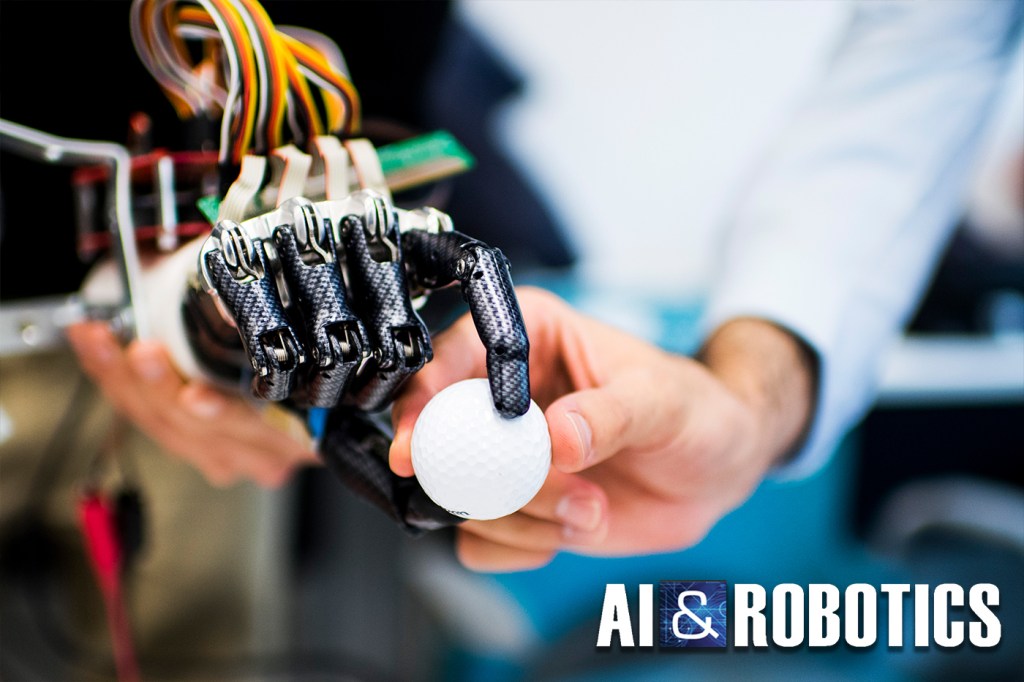

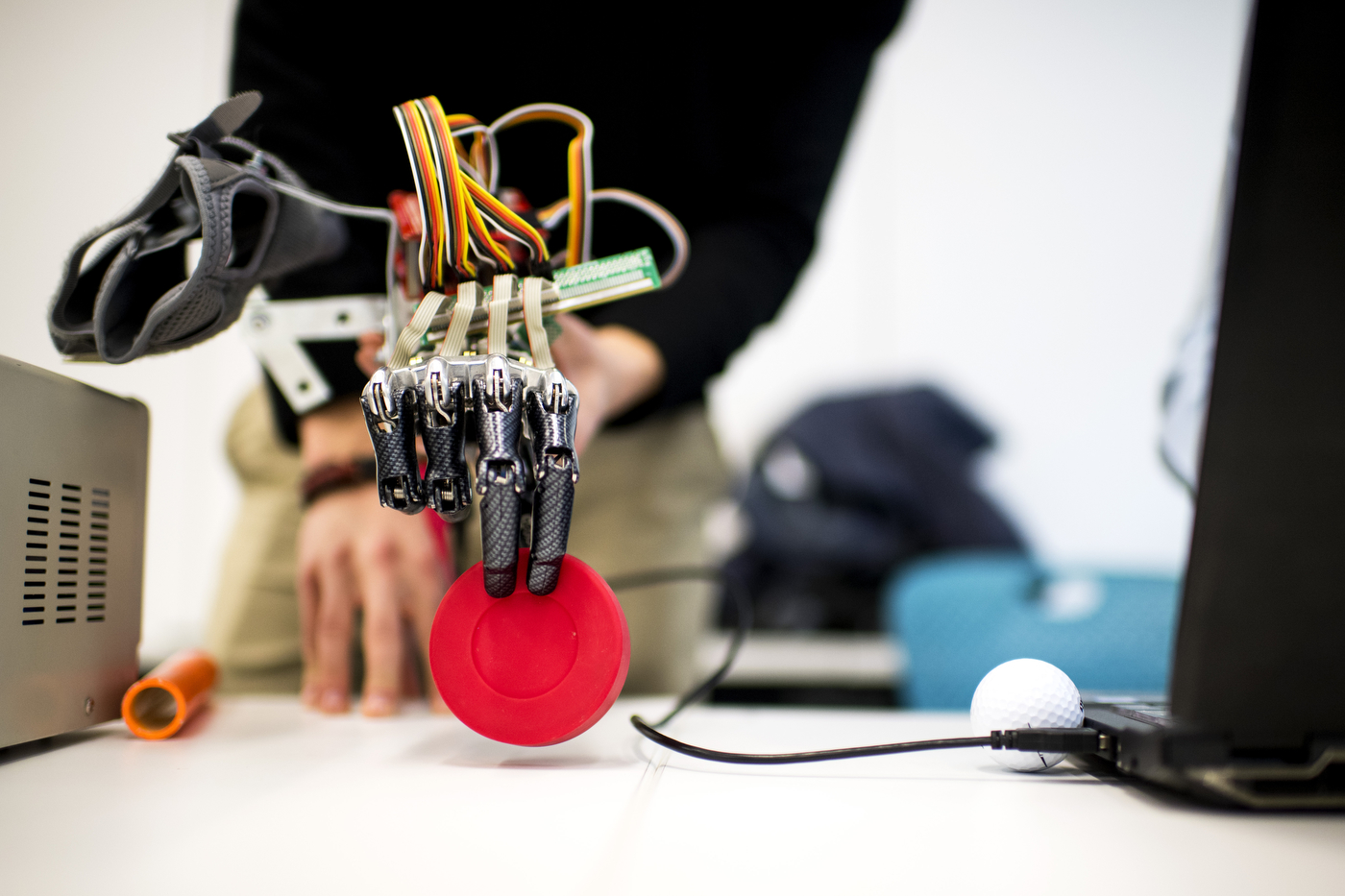

Building a smarted prosthetic hand

Mohammadreza Sharif is a doctoral student in Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and a member of the RIVeR Lab. His research focuses on robotic manipulation and grasping, with the ultimate goal of building and programming a robotic prosthetic hand for transradial—that is, below the elbow—amputees.

“One thing about this project that is both interesting and challenging is its multi-disciplinary nature,” Sharif said. “We are working in a group spanning a range of expertise, from machine learning and robotics to neuroscience.”

Researchers have figured out fairly well how to program robotic hands to grasp objects in a controlled lab environment, Sharif said. “But when it comes to real life, uncertainties arise, models fail, and unexpected things happen. We humans still know how to grasp under these circumstances, but robots have a longer way to go.”

He is working to solve that problem by integrating data, including electrical activity produced by skeletal muscles, that give the robot more context and allow it to make better predictions about user intent.

Sharif, who’s been studying at Northeastern since 2015, said the depth and breadth of the university’s robotics research has grown significantly in recent years. “This provides a very good atmosphere for those seeking experience working in a competitive and multidisciplinary environment,” he explained. “I believe this will make us ready to enter the job market, which needs people with such experience more than ever.”

Mohammadreza Sharif’s research focuses on robotic manipulation and grasping, with the ultimate goal of building and programming a robotic prosthetic hand for transradial—that is, below the elbow—amputees. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University