Should robots have rights?

As robots gain citizenship and potential personhood in parts of the world, it’s appropriate to consider whether they should also have rights.

So argues Northeastern professor Woodrow Hartzog, whose research focuses in part on robotics and automated technologies.

“It’s difficult to say we’ve reached the point where robots are completely self-sentient and self-aware; that they’re self-sufficient without the input of people,” said Hartzog, who holds joint appointments in the School of Law and the College of Computer and Information Science at Northeastern. “But the question of whether they should have rights is a really interesting one that often gets stretched in considering situations where we might not normally use the word ‘rights.’”

In Hartzog’s consideration of the question, granting robots negative rights—rights that permit or oblige inaction—resonates.

He cited research by Kate Darling, a research specialist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, that indicates people relate more emotionally to anthropomorphized robots than those with fewer or no human qualities.

“When you think of it in that light, the question becomes, ‘Do we want to prohibit people from doing certain things to robots not because we want to protect the robot, but because of what violence to the robot does to us as human beings?’” Hartzog said.

In other words, while it may not be important to protect a human-like robot from a stabbing, someone stabbing a very human-like robot could have a negative impact on humanity. And in that light, Hartzog said, it would make sense to assign rights to robots.

There is another reason to consider assigning rights to robots, and that’s to control the extent to which humans can be manipulated by them.

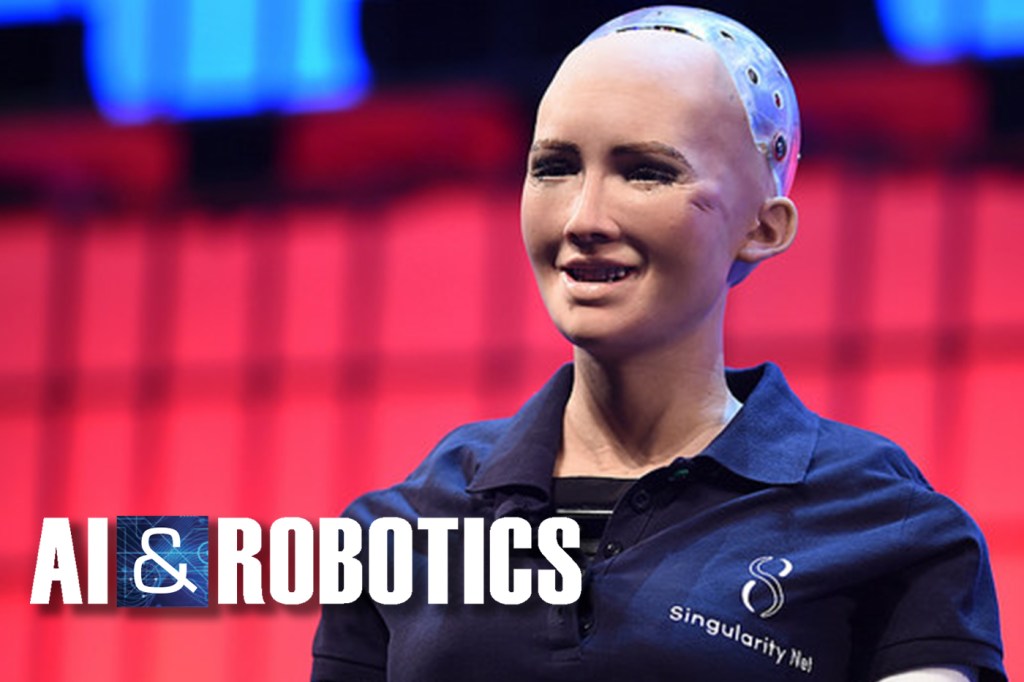

While we may not have reached the point of existing among sentient bots, we’re getting closer, Hartzog said. Robots like Sophia, a humanoid robot that this year achieved citizenship in Saudi Arabia, put us on that path.

Sophia, a project of Hanson Robotics, has a human-like face modeled after Audrey Hepburn and utilizes advanced artificial intelligence that allows it to understand and respond to speech and express emotions.

“Sophia is an example of what’s to come,” Hartzog said. “She seems to be living in that area where we might say the full impact of anthropomorphism might not be realized, but we’re headed there. She’s far enough along that we should be thinking now about rules regarding how we should treat robots as well as the boundaries of how robots will be able to relate to us.”

The robot occupies the space Hartzog and others in computer science identified as the “uncanny valley.” That is, it is eerily similar to a human, but not close enough to feel natural. “Close, but slightly off-putting,” Hartzog said.

In considering the implications of human and robot interactions, then, we might be better off imagining a cute, but decidedly inhuman form. Think of the main character in the Disney movie Wall-E, Hartzog said, or a cuter version of the vacuuming robot Roomba.

He considered a thought experiment: Imagine having a Roomba that was equipped with AI assistance along the lines of Amazon’s Alexa or Apple’s Siri. Imagine it was conditioned to form a relationship with its owner, to make jokes, to say hello, to ask about one’s day.

“I would come to really have a great amount of affection for this Roomba,” Hartzog said. “Then imagine one day my Roomba starts coughing, sputtering, choking, one wheel has stopped working, and it limps up to me and says, ‘Father, if you don’t buy me an upgrade, I’ll die.’

“If that were to happen, is that unfairly manipulating people based on our attachment to human-like robots?” Hartzog asked.

It’s a question that asks us to confront the limits of our compassion, and one the law has yet to grapple with, he said.

What’s more, Hartzog’s fictional scenario isn’t so far afield.

“Home-care robots are going to be given a lot of access to our most intimate areas of life,” he said. “When robots get to the point where we trust them and we’re friends with them, what are the articulable boundaries for what a robot we’re emotionally invested in is allowed to do?”

Hartzog said that with the introduction of virtual assistants like Siri and Alexa, “we’re halfway there right now.”