‘We were there to honor them’: Co-op student identifies, lays to rest veterans’ remains

On a hot, sunny day in May, Justine Newman stood at Washington Crossing National Cemetery in Pennsylvania, observing a military funeral with honors she’d organized for seven local veterans.

She didn’t personally know any of the veterans being interred; in fact, no one there did. Their cremated remains were among the small percentage of remains that the Chester County Coroner’s Office—like so many coroners’ offices across the country—take responsibility for when next-of-kin can’t be located or decline to take them.

For Newman, BHS’20, the ceremony was the culmination of work that began five months prior, when she started a co-op at the Chester County Coroner’s Office to learn more about forensic pathology, her field of study.

Early on, Newman learned the ins and outs of a coroner’s job—from arriving at a scene, to collecting information about the deceased, to contacting the next-of-kin. “I learned so much more than I ever hoped to,” she said of the experience.

As she progressed, Newman encountered a new challenge: Identifying and laying to rest the cremated remains of those people, occasionally homeless, whose identities weren’t known, or whose next-of-kin declined responsibility for them.

I didn’t get to meet these people, I didn’t know them, but in that moment I felt the weight of what we were doing. These are people who served our country, and we were there to honor them.”

Justine Newman

BHS'20

“We had names for a few people, a date of birth for most, but social security numbers for almost none,” she said.

The Chester County Coroner’s Office had 65 such remains, and for each, Newman tracked down as much information as she could through a web of different channels. Dave Daugherty, chief deputy coroner, emphasized the importance of Newman’s work.

“Nobody should just be forgotten,” he said. “Each of these people lived a life and they deserve recognition.”

Using what little information she had, Newman traced back through the people’s lives—contacting former doctors, employers, and others—to get a sense of who they were. Through a complex process that involved long hours on the phone with various federal agencies, she discovered that nine of the remains belonged to military veterans. Seven of them were eligible to be buried in a national cemetery will full honors; the other two had been in the reserves, but not long enough to be eligible for the same burial.

With the knowledge in hand, Newman began to plan a ceremony for the seven veterans: Byron Martz, Joseph Houghton, and Allan Maloney of the U.S. Marine Corps; Monte Weneck and Arthur Stroman of the U.S. Army; and Robert M. Rowe and Robert Pieczonka of the U.S. Navy.

“We had names for a few people, a date of birth for most, but social security numbers for almost none,” Newman said of the cremated remains of people whose identities were unknown. Photo by Adam Glanzman/Northeastern University

Newman contacted military honors groups for each of the three branches in which the veterans served and coordinated with the Washington Crossing National Cemetery to have all seven veterans interred on the same day, May 17.

In doing so, Newman developed a policies and procedures guide for the office, Daugherty said. “She created a step-by-step guide for completing the process,” he said.

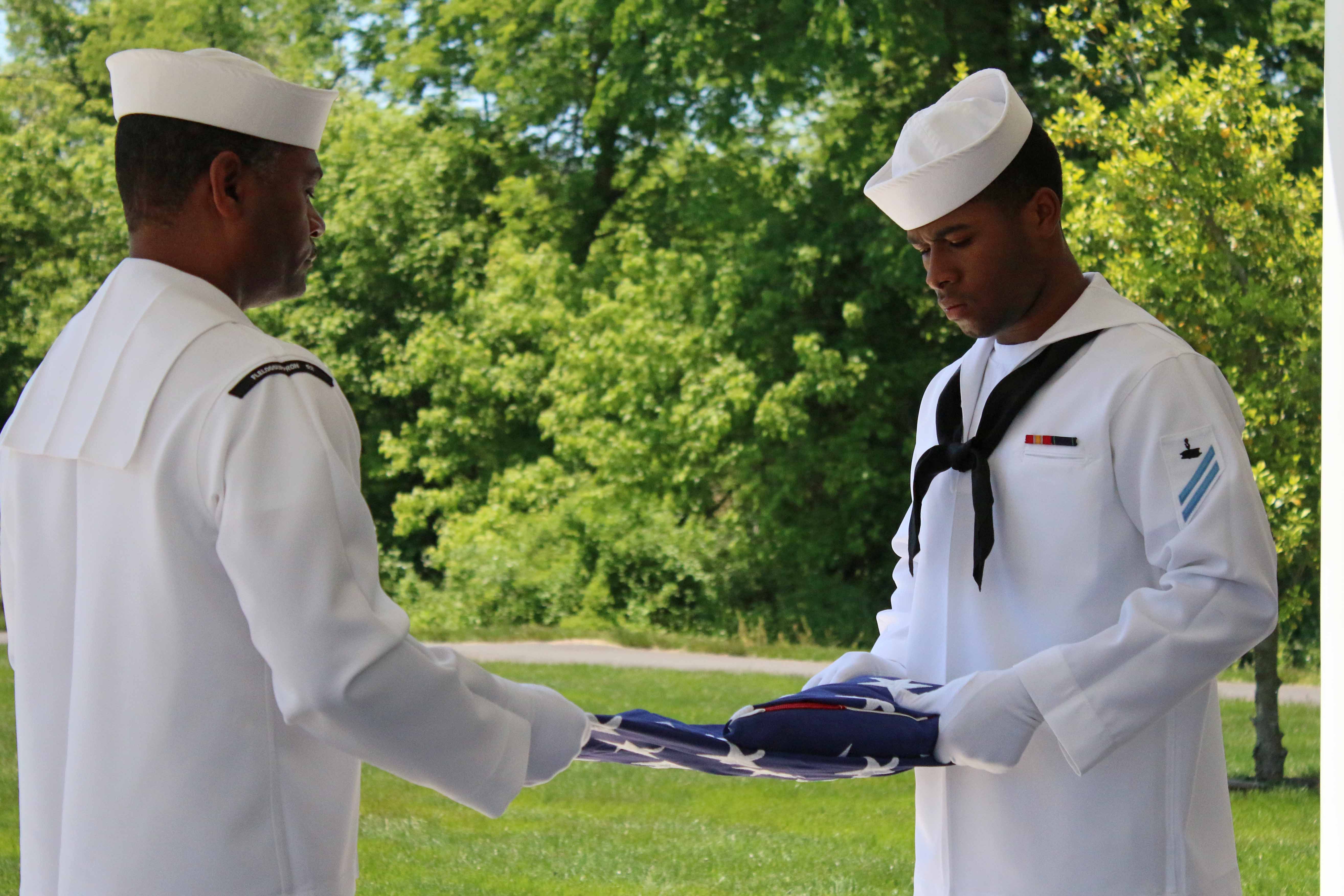

The veterans’ cremated remains were placed on a pedestal at the cemetery. The honor groups fired three volley shots at the start of the ceremony and played Taps before each branch folded a U.S. flag for the veterans. They presented flags to Anthony Wright, Newman’s co-worker at the coroner’s office, who donated them back to Washington Crossing to be flown over the cemetery. Then, the seven remains were placed in the same row in the cemetery’s columbarium, which was engraved with their names, rank, and branch of service.

“I didn’t get to meet these people, I didn’t know them, but in that moment I felt the weight of what we were doing,” Newman said, recalling the ceremony. “These are people who served our country, and we were there to honor them.”