Will NFL protests be seen as moment ‘the tide turned’ on race, social justice?

When track and field athlete John Carlos bowed his head and raised his fist during the 1968 Summer Olympics in protest of racial and social injustices in America, he knew the significance of the moment.

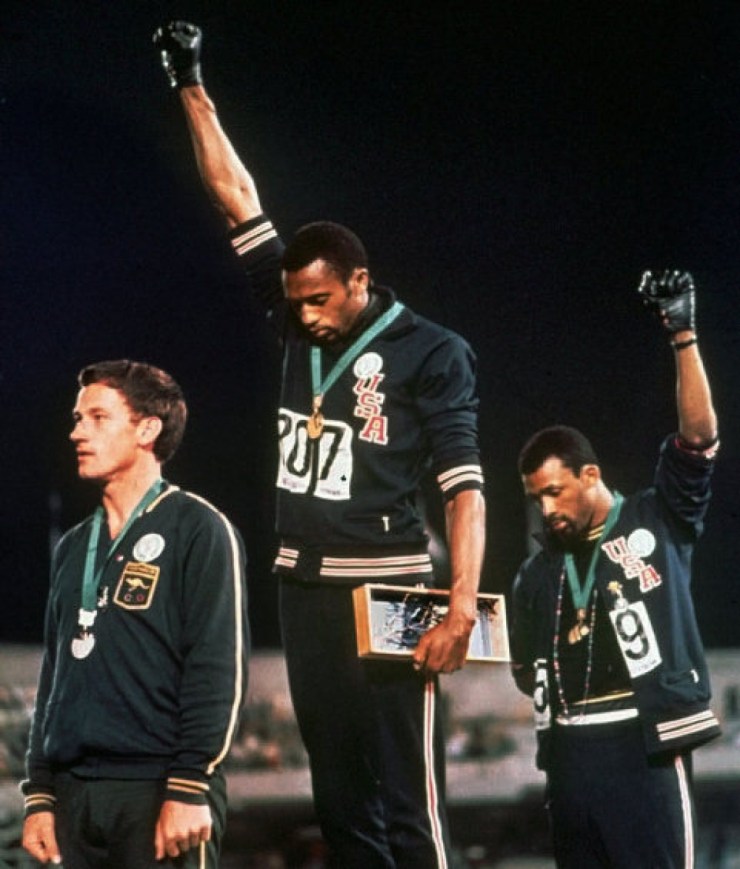

In this Oct. 16, 1968, file photo, United States athletes Tommie Smith, center, and John Carlos, right, extend their gloved fists skyward during the playing of the “Star-Spangled Banner” after Smith received the gold and Carlos the bronze for the 200-meter run at the Summer Olympic Games in Mexico City. (AP Photo/file) Creative Commons license applies.

“I had an understanding that this would be something enormous,” said Carlos, whose demonstration on the winners’ podium after placing third in the 200-meter race in Mexico City stirred up a political controversy. “The movement was like a mushroom afterward. As it grew taller it also grew wider.”

Just last week, the national spotlight turned again to a similar movement—one started a year ago by then-San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick—wherein players in the National Football League and other professional sports leagues take a knee during the national anthem.

The two protests are offshoots of the same source, Carlos said. “The protest is about the unfair treatment of black Americans. It’s about calling attention to the unfair playing field; about the atrocities that happen to black Americans on a daily basis without consequence. In that sense, 1968 never left. Fifty years ago, we were architects, we were agriculturalists; we planted the seeds and you see the fruits of our labor now.”

A carefully planned moment

Carlos, the bronze medalist in the 200-meter sprint, and Tommie Smith, the gold medalist in the same event, raised gloved fists during the medal ceremony at the 1968 Games. Peter Norman, an Australian sprinter who won silver in the race, stood in solidarity.

They would become some of the most iconic athletes of the 20th century, and their radical yet peaceful gesture would be seared into history.

Carlos said he and Smith had carefully planned the moment and had taken stock of the opportunity they had to stand up to racial discrimination in America.

Black celebrities are in a unique position when it comes to politics because they become spokespeople for the entire black population, whether they want to or not. That’s both a blessing and a curse.

Sarah J. Jackson

assistant professor of communication studies at Northeastern and a scholar of social movements

“Facing the flag and hearing the national anthem, I had to wonder, ‘Does that cover me?’ It’s a parallel situation to now,” he said. “The American flag is supposed to encompass all Americans. Mr. Kaepernick chose to make a statement relative to those issues. He’s not disrespecting the flag; he’s saying—like I was saying 50 years ago—that he wishes the flag would wrap its arms around him like it wraps its arms around other Americans.”

The ‘powerful platform’ of sport

Like Carlos, Kaepernick and other black athletes and celebrities often find themselves in a distinct situation when it comes to using their prominence to speak out, said Sarah J. Jackson, assistant professor of communication studies at Northeastern and a scholar of social movements.

“Black celebrities are in a unique position when it comes to politics because they become spokespeople for the entire black population, whether they want to or not,” she said. “That’s both a blessing and a curse. They have the opportunity to introduce political interventions, but they’re also held to a double standard to which other people in the public eye aren’t held.”

The platform athletes have to reach the general public, while similar in reach to that of other types of celebrities, is also unique to them, said Dan Lebowitz, executive director of Northeastern’s Center for the Study of Sport in Society. Sports in general are a unifying experience, he said, and athletes are the primary catalyst.

“Athletes have this powerful platform because of that common denominator of sport—it has the power to be a social justice change-maker.”

“Athletes have always been that beacon of social justice. You have heroes like John Carlos raising his fist in the air back in 1968,” Lebowitz said. “And now you’re seeing more athletes making powerful statements—they’re aware of the tremendous power they have.”

He added, “Sport is a medium that has vast potential to build common ground and to begin a conversation about conflict resolution. As such, these athletes have embraced that potential and the power of their collective voice to raise our national consciousness and start a long over-due conversation about the systemic racism that has caused untold inequity, exacted constant historical violence upon people of color, plagued our country and imperiled our future. This athlete activism is not about defamation of the flag, it is about the need for the civil discourse and the change that is needed and protected under it.”

‘The intensity on either side’

And yet for all the unifying qualities of sports, when athletes took a knee, not all fans were behind them. Nor, of course, were all politicians—namely President Donald J. Trump, who last week called out protesting athletes in derogatory terms.

It’s a complicated issue for people who conflate the flag and the national anthem with “honor, glory, sacrifice, and in many cases, their own loss,” said Northeastern’s Martin Blatt, professor of the practice in history and director of the university’s Public History program.

Blatt, whose research includes a study of the significance of historic monuments, referenced what Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto told The New York Times about the recent demonstrations. Peduto said, “If you’re a gold star mom, the idea of kneeling through the national anthem is beyond disgraceful and is a cause of emotional harm. But if you’re a mom who lost their child in the streets of America, the idea of kneeling is saying to you that your voice is being heard.”

Blatt said of Peduto, “He captures the intensity on either side. Many people equate the flag and the anthem with the fact that they’ve lost someone in the military. To those people, anyone who is disrespectful of that, who is denigrating the flag or the anthem, is disrespecting the memory of those who fought and died. It’s conflating a whole bunch of things together.”

Carlos said that for Smith, Kaepernick, himself, and others who have protested during the anthem, it’s not about disrespecting the country or the sacrifice so many have made. “It’s not that at all,” Carlos explained. “The flag just happens to be the medium by which we had this opportunity to bring about focus and draw attention to this uneven playing field where black Americans have been circled out.”

Jackson echoed Carlos’ explanation. “A lot of these narratives about patriotism and nationalism obscure the fact that what Colin Kaepernick—and many before him—wanted us to talk about were issues of race and inequality,” she said.

Women’s professional sports at the forefront of social justice advocacy

The first white professional athlete to take a knee during the national anthem wasn’t an NFL player, but rather U.S. Women’s Soccer League player Megan Rapinoe. In fact, women’s professional athletes have been at the forefront of advocating on social justice issues, though their actions haven’t produced the kind of front-page splash as have the NFL protests.

Part of the disparity, Jackson said, “is just plain cultural sexism.” But another part is that women’s professional sports are themselves the result of political activism.

“The tide has turned on this. This is going to continue to be a cultural struggle, especially in this really polarized cultural environment in which we find ourselves. This controversy may go on for some time, but when we look back in the history books, I think this will be the moment when it’s clear the tide turned.”

“Women’s professional sports exists because of activism,” Jackson said. “Women had to claim a space, a right to play, to have these programs funded, and so on. Title IX came about because of feminist activism. Thus, many people in women’s sports already have a more accepting view of activism, and of thinking critically about culture.”

The moment ‘the tide turned’

The demonstrations in athletic venues across the U.S. have sparked a national conversation. And according to Lebowitz and Jackson, it isn’t a conversation that’s going to end any time soon. “These athletes have created a necessary nexus toward building anti-racist resistance—toward building a sustainable movement,” Lebowitz said. “This is not a conversation that you can put back in its box.”

Jackson said, “The tide has turned on this. This is going to continue to be a cultural struggle, especially in this really polarized cultural environment in which we find ourselves. This controversy may go on for some time, but when we look back in the history books, I think this will be the moment when it’s clear the tide turned.”

“Look at it this way,” said Carlos, who has spent the past 50 years fighting the same fight, “a heavyweight boxing match is 15 rounds. The name of the game is, if you’re going to be successful, you have to go the distance.” He continued, “Because this isn’t for me, or even for Mr. Kaepernick—you do all this to make a better situation for your kids; to turn that stampede around for them.”

Thinking about it further, and with a sharp laugh, he added, “Me, Mr. Kaepernick, Tommie—we’re like that nasty medicine your mom used to make you take as a kid. It doesn’t have to taste good or look good or feel good for it to be good for you. But somewhere down the line, America is going to look and feel better because of us.”