Building a ‘thriving civic data ecosystem’ in Boston

Last month, about 20 researchers and community stakeholders convened at Northeastern to talk data—specifically, newly published data from surveys with Boston residents on topics ranging from demographics to perceptions of community safety.

The Boston Area Research Initiative, or BARI—which is based at Northeastern’s School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs—led the meeting, which was designed to demonstrate how community organizations can use a variety of online tools BARI has developed to learn more about the neighborhoods they serve and promote informed advocacy on their behalf.

“We are focused on trying to build a thriving civic data ecosystem in Boston,” said BARI co-director Daniel T. O’Brien, assistant professor with joint appointments in the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs and the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Northeastern.

Launched in 2011, BARI is an interuniversity research partnership between Northeastern and Harvard University, in conjunction with the city of Boston. It focuses on spurring cutting-edge research in the Boston area that advances both scholarship and public policy.

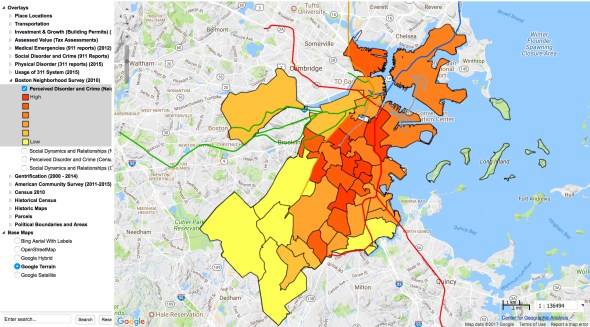

One of BARI’s primary projects is the Boston Data Portal, a National Science Foundation-funded infrastructure that harvests and publishes a variety of data related to Boston and its neighborhoods—from census and social media data, to city building records and 311 calls. The portal includes an interactive map that allows users to better understand the social dynamics across Boston’s neighborhoods. For example, they can view and compare by neighborhood everything from the age of buildings to incidences of 311 and 911 reports.

The results of the Boston Neighborhood Survey from 2010 on topics such how residents perceive disorder and crime in their neighborhoods were recently added to the portal’s map, and at the meeting last month BARI program coordinator Samantha Levy showed participants how to access this data and compare it alongside other neighborhood dynamics—such as the locations of schools and community centers.

Click the image above to explore the interactive map.

Click the image above to explore the interactive map.

“We think the Boston Data Portal can be used for many different things,” Levy said. “There are a lot of data-related demands nowadays on nonprofits, and the portal is useful for nonprofits to learn more about the communities they’re serving to enhance their advocacy goals and evaluate their internal operations.”

Few city-university collaborations have data infrastructure that is making research-quality data readily available to the public nor are they doing much to engage nonprofits and grassroots community groups, O’Brien said. “We saw major opportunities for researchers and policymakers to work together,” he noted. Not only does BARI run community-based trainings, but the researchers like O’Brien who are involved also use them as teaching tools in the classroom for their students.

O’Brien explained that BARI’s work and his Northeastern research are intertwined. In his research, which focuses primarily on Boston, he uses large, administrative data sets—i.e., Big Data—in conjunction with traditional methodologies to explore the behavioral and social dynamics of urban neighborhoods.

One particular area of focus is the “broken windows theory”—that acts of public disorder in neighborhoods lead to future crime. He just wrapped up a five-year research project studying “custodianship,” or how people take care of their neighborhoods.

“In all these different things,” he said, “the common theme is they all leverage modern digital data to ask interesting questions with scholarly and practical implications.”