The value in news outlets moving to ‘reach across the political divide’

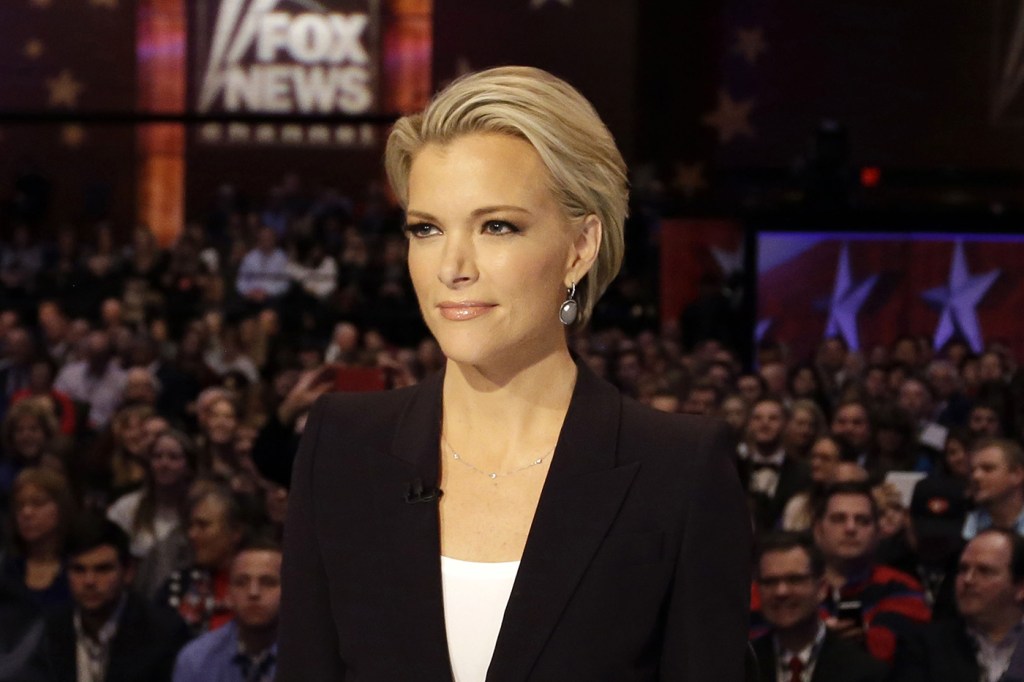

In January, prominent Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly announced she would be moving to MSNBC. And recently, The New York Times started highlighting the best partisan writing of the day, as well as hired conservative op-ed columnist Bret Stephens. What’s driving news organizations to more clearly feature voices associated with one side of the political aisle or the other? Is it a business move, to take advantage of competitors’ stumbles? Or is it a journalistic move, to feature a wider range of clearly defined political viewpoints?

We asked John Wihbey, assistant professor of journalism, about the phenomenon. “Most news executives are trying to figure out how to increase their depth of insight into the new administration,” he said. “They also want to grow their audiences amid a very fluid landscape, where many traditional, mainstream, center-right Republicans may be up for grabs and liberals are highly engaged with news.”

And while some efforts may work better than others, Wihbey added: “I applaud any efforts to reach across the political divide, whether it’s through web linking or hiring new voices. We have to try. There’s no choice.”

In a news environment where many outlets are unabashedly partisan, should news organizations strive for nonpartisan writing? Or is it better to offer a balanced menu of clearly partisan writing?

Clear, compelling, nonpartisan news stories have the best chance of reaching a broad audience and establishing a common set of agenda items and baseline facts that can facilitate informed citizenship and democratic self-rule. At the same time, commentary and argument are vital for the functioning of deliberative democracy as well—the pamphleteer and the partisan printer are core to our history and culture, after all—and we should expect value judgments to remain a big part of news.

A balanced menu of clearly partisan writing, as you say, would conform to our ideals in academia of rational argument and Socratic dialogue—it is worth a try, particularly in our hyper-partisan era, and it represents a good experiment. Some of our great political magazines have represented a version of this at various times. But in my view, it’s not reasonable for all news companies to conduct themselves along these lines, nor to expect all citizens to consume public affairs news in this way. Most people do not pay a lot of attention to civic or political issues. Most issues are not salient in their lives. They don’t have much time to weigh competing arguments. It is costly (in terms of time and effort) to wade through partisan arguments, especially for low-information voters and busy average citizens.

Increasingly, what social scientists are learning about how people make sense of information and form value judgments is that shared community narratives matter more than particular facts. If you are looking to change minds about issues, the best way is to provide straightforward, non-sensational accounts of fact patterns and use what are called “surprising validators” for context and interpretation where conclusions are reached. This might mean, for example, quoting a former oil executive who says the seas are rising and we need to address human-induced climate change, or a labor union leader who also sees the benefits of free trade for workers in developing nations.

Partisan newspapers were the norm in America until the 1950s, when new federal regulations went into effect and helped shape journalistic neutrality. Do you see the recent wave of explicitly partisan reporting as the beginning of a return to formative journalism in the U.S.?

It is true that broadcast regulations such as the Fairness Doctrine and equal time provisions help moderate overt partisanship—although periods like the late 1960s saw major partisan divisions. But another reason that the journalistic professional norm of objectivity and neutrality prevailed to a large degree is that it provided a lot of space, a big tent of sorts, in which to invite advertisers of all kinds. Now that the ad-supported model is failing, particularly for newspapers, the business motivation to stay impartial and fair is eroding. That may be worrisome over the long run. Everyone in media has seen over the past decade or so that going heavily partisan can work in terms of assembling an audience, especially on cable and the web. It will be a big temptation for everyone. I do think we are returning to an older tradition in some respects, but the structure of society is different now, so I don’t want to conclude that everything will be fine.

The ideal of the “news bundle”—the broad mix of straight news, commentary, sports, weather, etc.—that we saw embodied in the nightly news program or the metropolitan newspaper of the mid- to late-20th century is something as close to ideal as could be imagined in a democracy. It was enabled by limited media choice. We are now testing whether a complex, modern democracy can work in a highly partisan environment where news consumption is increasingly defined by personalization or selective exposure. As you suggest, the press in the 19th century—indeed all the way back to the country’s founding—was highly partisan until the post-war period, ending with the rise of cable and the internet. Yet the world was a less complex place in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.

One thing that I worry about is that our era not only features increasing partisanship reporting but also a relentless denigration of nonpartisan reporting and news by leaders. The phenomena that most erode public trust in news are tabloidization, which is a “self-inflicted wound” by news media themselves, and criticism by elites such as political leaders. There is short-term gain politically to bashing news media, but over time it will prove nearly impossible to govern and pass legislation that addresses pressing issues if there is no broad public consensus of what’s important or factual. The Pew Research Center’s latest survey findings in this regard are truly frightening, with a historic partisan gap relating to the value of news media in our democracy.

All of that said, some of the political science literature relating to this indicates that partisan-driven media can also motivate quality civic engagement of various kinds. Partisan activism is not a totally negative trend, even if it feels rancorous in style, and I think we all value “activism” in a democracy, which is closely associated with partisanship. So, it’s complicated. The era of three TV networks and homogenous media, with limited choice, also suppressed many diverse voices and issues.

How do you think the 2016 election has changed newsrooms and news coverage?

It has certainly emboldened news organizations in some cases to become more assertive and aggressive about their watchdog mission, symbolized in part by The Washington Post’s promotion of its new motto, “Democracy Dies in Darkness.” A number of organizations have seen increased ratings and subscriptions, particularly from left-leaning audiences. This has generated some amount of hope for a sustainable business model, for an industry that has seen one of the most rapid declines of any sector in U.S. history. (About half of the entire commercial editorial labor force has evaporated over the past two decades.) Some of the emerging nonprofit news organizations have seen a lot of money flowing in. Great news organizations such as the investigative nonprofit news outlet ProPublica have talked about some new operating procedures in this era—more journalistic transparency, collaboration, creativity, and flexibility.

Do you think the addition of conservative voices in fairly liberal organizations is more of a news judgment or a business decision?

Having commentators of different political persuasions is, in the abstract, a good thing. Newspapers had a lot of success with this model for a long time, with dueling columnists. As new presidential administrations come in with a left or right tilt, news organizations typically try to respond. This can be for cynical reasons (like pandering to audiences) but it can also be for the best reasons: Getting well-sourced, experienced commentators who have deep knowledge of communities on the political left or right. Most news executives right now are trying to figure out how to increase their depth of insight into the new administration. They also want to grow their audiences amid a very fluid landscape, where many traditional, mainstream, center-right Republicans may be up for grabs and liberals are highly engaged with news.

There is a basic tension playing out in the media world right now, what you might think of as “brand vs. tribe.” In the past, media could use the power of their brand to bring in diverse, conflicting voices and build an audience composed of many partisan stripes. It is not clear how that can be done in an era of nearly infinite media choice and personalization of information. You may be much more likely to go with your political tribe and its house organ news outlet. A centrist, “mainstream” media brand may lack the convening power, as technological and economic forces pull apart the big tent and the branded bundle. Still, I applaud any efforts to reach across the political divide, whether it’s through web linking or hiring new voices. We have to try. There’s no choice.