Top-ranked Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu fighter reflects on his success

Injuries be damned.

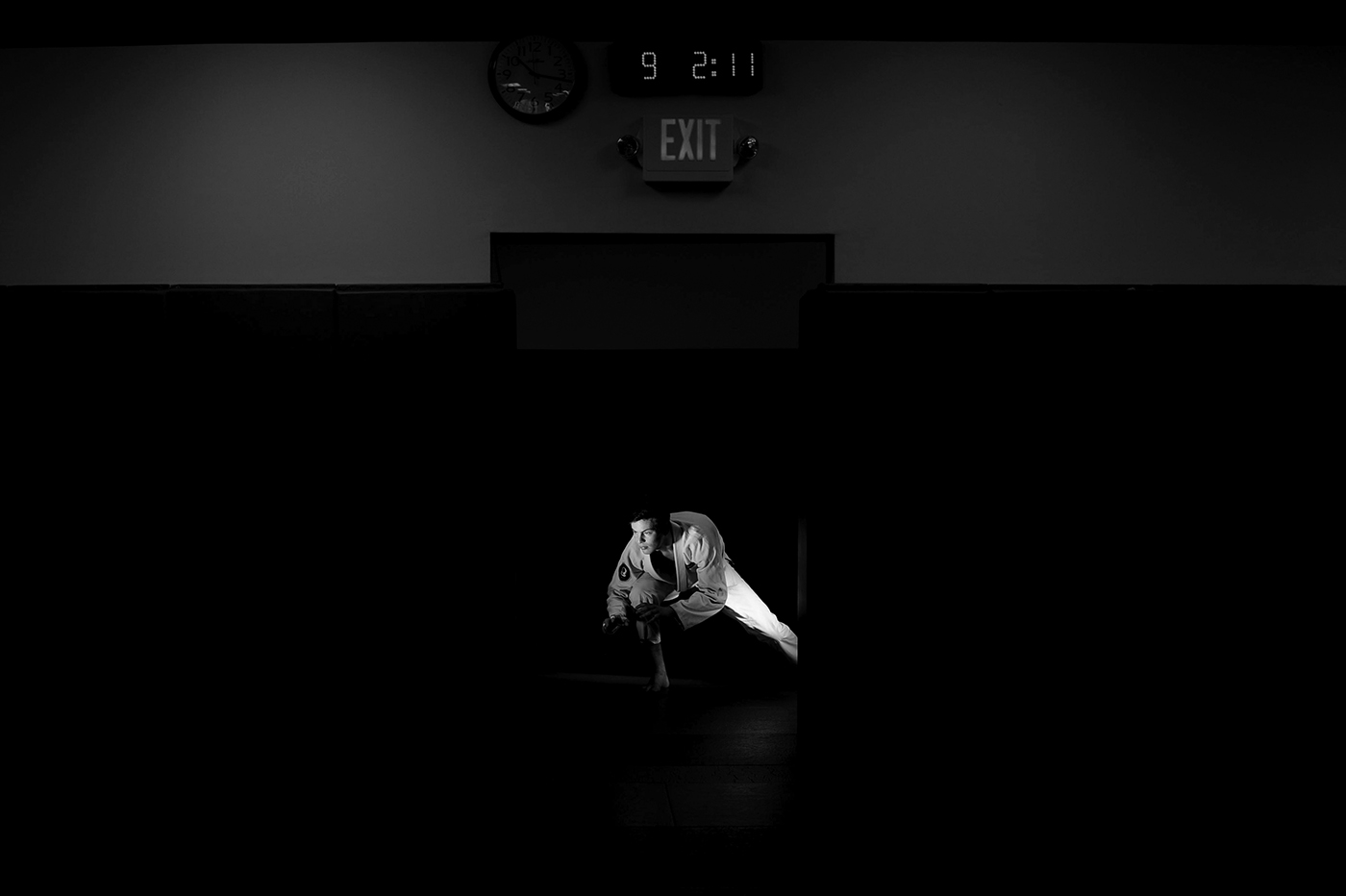

Henry Edson, the No. 1 fighter in the International Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Federation’s white belt heavyweight division, will do whatever it takes to win—even if it means training with broken fingers or fractured feet.

“Just tape it up,” says Edson, SSH’19/MS’20, a second-year student at Northeastern University. “When you get to the top of the podium, you realize that all the sacrifices you made have been worth it.”

Edson has only been training for 18 months, but he’s already won 12 gold medals in competitions across the country. His latest victory, in the 2017 Pan Jiu-Jitsu IBJJF Championship, held in March in Irvine, California, was perhaps his most impressive.

He defeated all three of his competitors in a combined total of 4 minutes, 20 seconds, far less than the five-minute time limit for one white belt match. The gold medal fight lasted all of 9 seconds, the quickest match of the entire tournament.

“I’m very fast and very aggressive,” says Edson, who, at 6-feet-5-inches, 202 pounds, is taller and leaner than the vast majority of his opponents. “If I think I can end the fight soon after it starts, I’m going to do it.”

For Edson, the victory was particularly special, the icing on the proverbial cake. “Before the tournament, I told myself that I had already won,” he explains. “I had been training three times per day through injuries that most people would be on crutches for.”

‘I was jealous of professional hockey players’

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu is a modern martial art, created in Brazil in the 1920s by national sports hero Helio Gracie. The aim of a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu practitioner, known as a jiujiterio, is to score points by throwing his opponent to the ground and immobilizing him or forcing him to submit with chokes, strangles, and joint locks.

Edson trains at Kimura Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, a popular studio in Watertown, Massachusetts. He is currently working out twice a day, sparring and drilling 45 minutes at a time, but he’ll soon begin training three times per day in preparation for the World IBJJF Jiu-Jitsu Championship in June.

His father is a black belt in karate, but his decision to take up Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu stemmed from his desire to learn self-defense as well as his longstanding interest in the art of fighting. He grew up in Newton, Massachusetts, playing high school lacrosse. He was good—he planned to compete at the Division 1 level in college—but he often got injured and lamented the fact that fighting was illegal in his favorite sport. “I was jealous of professional hockey players,” he quips.

In 2015, he found his calling, taking a free class at the the Watertown studio and never looking back. “I love how personalized the sport can be,” says Edson, who is sponsored by the Chaos & Order apparel line and is looking for additional sponsors to cover travel costs for out-of-state tournaments. “You can develop your own style and use virtually every part of your opponent’s body as a target, from their neck to their knees.”

‘For the love of the art’

Edson’s athletic accomplishments are impressive. But they’re even more spectacular when you consider that he studies as hard as he trains, earning a near perfect 3.95 GPA in the fall semester.

How does he balance school and sport? “I bring my homework to the gym and study in the locker room,” he explains, noting that he hits the books immediately after teaching a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu class for kids. “Once you figure out how you learn best, everything else is easy.”

If all goes according to plan, Edson will earn his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in international affairs by spring 2020. He says his courses have helped him develop a strong understanding of different cultures while honing his ability to work with people from all walks of life—two skills that have made it easy for him to form tight bonds with his teammates.

His master, Jean Kleber de Freitas, one of the sport’s top instructors, believes that he can be a world champion at the highest level. “Obviously that’s kind of a big deal,” says Edson, “but it also comes with a lot of pressure.”

For now, he’s focused on finishing the spring semester on a high note and preparing for the world championship in June. When he graduates, some three years for now, he fully expects to carve out two careers—one, in international affairs, to pay the bills, and the other, in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, for the sheer love of the sport. “Unlike mixed martial arts or boxing, there’s no money in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu,” he says. “I do it for the love of the art.”