Will Electoral College add more drama to historic election?

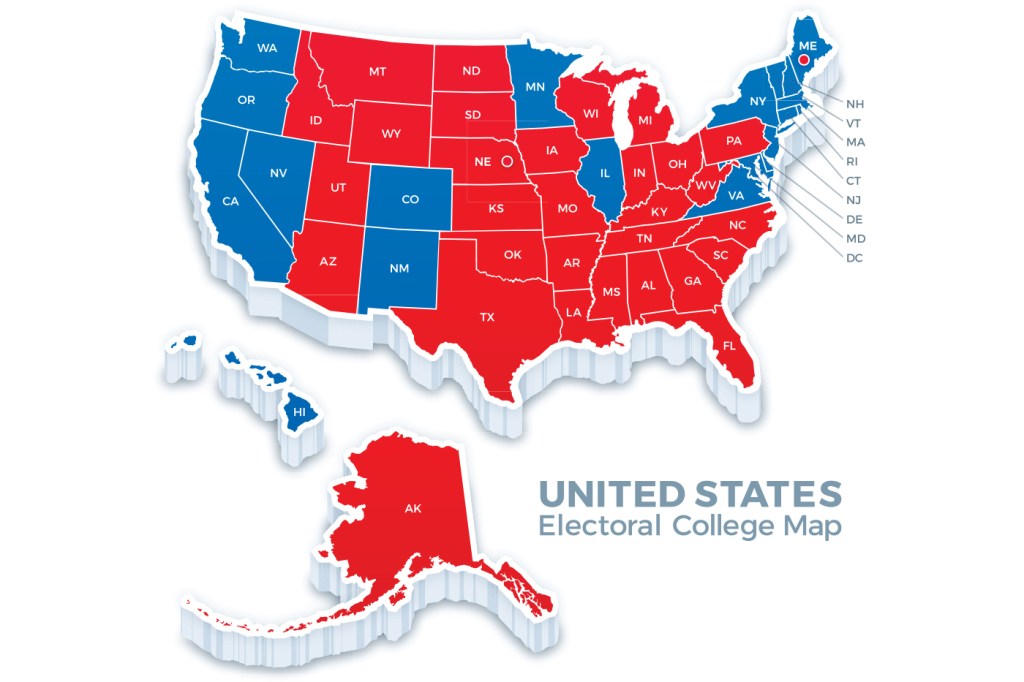

All 538 members of the Electoral College will gather in their respective state capitals on Monday to formally cast their votes in the presidential election. Many Democratic electors have been lobbying their Republican counterparts to vote against President-elect Donald Trump, but it is unlikely that they will be able to gin up enough support to deny Trump the 270 electoral votes needed for him to win the presidency.

If Democratic electors do convince enough Republican electors to disavow Trump—and neither Trump nor Hillary Clinton receives a majority of the electoral votes—the Republican-led House of Representatives will decide who becomes president.

We asked two faculty experts—William Crotty, elections specialist and professor emeritus of political science, and Dan Urman, assistant teaching professor and director of the undergraduate minor in law and public policy—to explain the mysteries behind the Electoral College and how Monday’s vote will likely unfold.

First of all, who are these 538 electors and how did they get picked to be electors?

Urman: Like so many aspects of American politics, our Constitution says very little about the Electoral College. Article II, Section I says that “no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.” That probably represented the founders’ desire to have federal elected officials avoid conflicts of interests—they would probably choose themselves. Instead of constitutional text, the process of choosing electors seems to be a product of norms, practices, and history.

The process of choosing electors involves two steps. First, before the election, each political party chooses their electors (this varies by state, and often takes place at a party convention or by party leaders). Electors range from party elites, elected officials, or individuals connected to the candidate. Second, on Election Day, voters cast their ballots for president. In doing so, the voters are choosing electors (some states even list the name of the electors on the ballot, but this is not the case in Massachusetts).

Approximately 30 states, by law, require electors to follow the election results, and even include modest penalties (fines, disqualification) for an elector voting for someone other than the party nominee. I am not aware of any prosecutors bringing charges against one of these so-called faithless electors; it is quite rare.

What happens after the electors cast their votes?

Crotty: If the Electoral College cannot make a decision, the process moves to the House of Representatives. If no candidate receives a majority from the Electoral College, the House of Representatives chooses from among the top three vote-getters. Each state delegation has one vote. A quorum consists of two-thirds of the states present with a majority needed to decide the winner.

In 1824, the House, which had the power to make the decision, did not choose the popular vote winner, Gen. Andrew Jackson, a populist from the West who was distrusted by those in power. Jackson threatened an end to the Virginia-Massachusetts monopoly of the presidential office. The decision caused an uproar. Jackson ran again in 1828 and won both the popular vote and the Electoral College vote.

In 1876, in a bitterly contested and history-changing presidential vote, three southern states—South Carolina, Florida and Louisiana—submitted two conflicting official sets of results to the Electoral College. A special commission consisting of members of the House, Senate, and Supreme Court was established to decide the outcome. In a political solution, the majority vote winner, reformer and Democratic candidate Samuel Tilden of Illinois lost to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio when the three states’ electoral votes were given to Hayes. The states in question and the South more broadly negotiated a deal with Hayes, stipulating that if they gave him their votes, he would withdraw all federal troops from the post-Civil War South, thus ending reconstruction and with it the national government’s involvement in state concerns.

The states would be left to manage their own affairs as they saw fit—a promise some candidates made to southern states in response to the civil rights revolution almost 100 years later, in the 1960s. The consequence was violence and repression—lynchings, murders, beatings, government- and privately-enforced segregation and the economic and political subjugation of blacks, which entered its worst phases. It continued up to 1965 and the enactment of the Voting Rights Act by the Johnson administration.

The message is that fooling with the popular vote results as filtered through the institutional structure of the Electoral College is dangerous stuff and to be avoided. The outcome of a presidential election, whatever the electors’ personal views, needs to be honored. If the process is the problem, change it.

Many Republican electors—even some who don’t like Trump—have told The Associated Press that they “feel bound by history, duty, party loyalty, or the law to rubber-stamp their state’s results and make him president.” If that’s the case—“If this campaign reveals that electors by and large feel compelled to behave like ‘party lackeys and intellectual nonentities,’ as Columbia Law School professor David Pozen wrote in a New York Times editorial, quoting Justice Robert Jackson—then what’s the point of the Electoral College? On the other hand, wouldn’t an Electoral College revolt undermine the democratic norms that have governed presidential elections for centuries?

Urman: Norms matter. We saw them weaken several times this year, whether it involved a candidate refusing to release his tax returns, the president-elect having zero experience working in government, or the popular vote-getter winning by such a large margin (nearly 3 million votes). When I think about the rule of law, it means people agree, in advance, to a set of procedures and abiding by the results of that process. It cannot simply be heads I win, tails you lose. When electors ran on both parties’ tickets, they pledged to support the state winner. Similarly, the voters thought the electors would select the state’s popular vote winner (except for Nebraska and Maine).

This scenario is extremely unlikely to happen, because 37 electors would have to refuse to vote for Trump. Even if they did so, and it threw the process into complete chaos, the House of Representatives would ultimately select the president. Because of our norms, I believe the House of Representatives would choose Trump. I shudder to think about what he and his supporters would do if anyone else became president.

Hopefully, as professor Pozen suggests, this year’s election will inspire the country to reflect on the Electoral College. As noted, it currently functions as a rubberstamp for state election results. Constitutional originalists should be troubled by the fact that electors do not vote their conscience—as Alexander Hamilton had hoped—because the founders wanted electors to exercise discretion. We will not eliminate the Electoral College, mostly because the small states that benefit from it will not support a constitutional amendment. The National Popular Vote movement, also unlikely, is a slightly more plausible solution to our current system.

Trump is unpredictable. If the Electoral College stops him from becoming president, what do you think he will do?

Crotty: If Trump is denied his victory, we know what he will do. He will repeat his behavior in the campaign. There will be accusations of a “rigged election,” “crooked” politicians, a politics that ignores people, control by a Washington-based elite, and more. He will fill the TV screen, send endless tweets, introduce equally endless lawsuits—a winning strategy for Trump—and call for his supporters to take action. It would be ugly and what would come out of it all is far from clear.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated 1924 as the year the House did not choose popular vote winner Andrew Jackson. In fact, the year was 1824.