3Qs: How to tame the Twitter haters

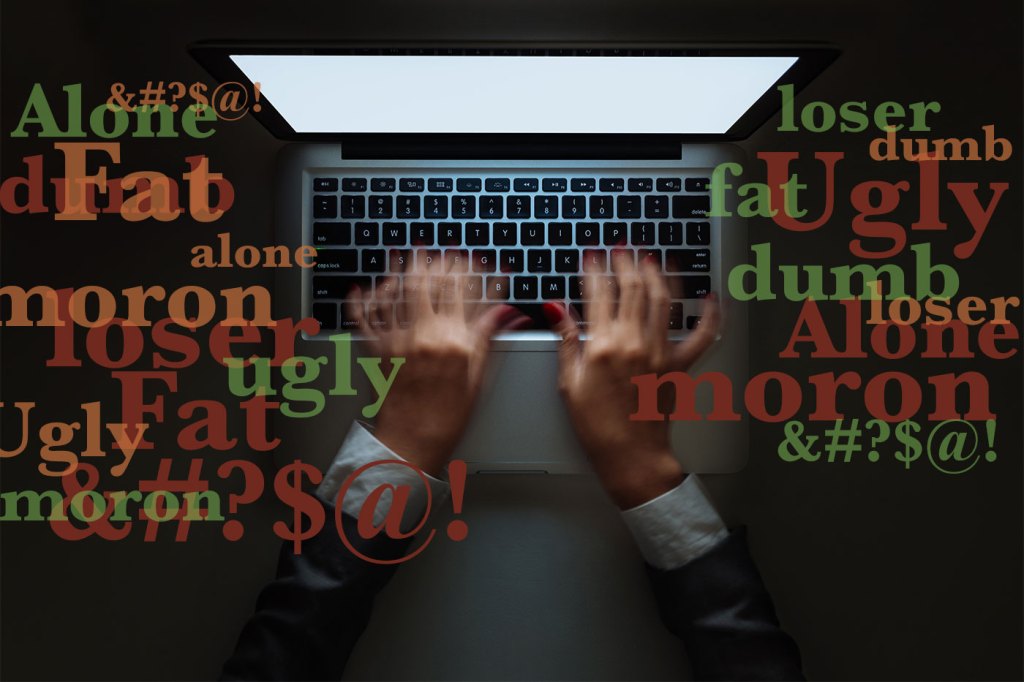

A score of Twitter users were banned by the social media service last week for hurling a spate of racist and misogynistic remarks at Ghostbusters star Leslie Jones. The most prominent user to be barred from Twitter was Milo Yiannopoulos, a technology editor for Breitbart who encouraged his followers to bombard the actress with hateful tweets, but he was far from the only internet troll to get the boot from the microblogging site.

How does online anonymity affect the way people act toward each other in the virtual world, what could social media sites like Twitter do to curb targeted attacks, and when does free speech cross the line from harmless banter to abuse?  We asked Joseph Reagle, assistant professor of communication studies, expert on internet trolling, and author of the 2015 book Reading the Comments: Likers, Haters, and Manipulations at the Bottom of the Web.

We asked Joseph Reagle, assistant professor of communication studies, expert on internet trolling, and author of the 2015 book Reading the Comments: Likers, Haters, and Manipulations at the Bottom of the Web.

In a 2014 interview on the topic of web culture, you noted that there has “long been this suspicion that if we’re anonymous, we lose accountability and are most likely to act horribly.” But you also acknowledged that “people say horrible things on Twitter all the time under their own names.” In the final analysis, what role does online anonymity play in the internet’s culture of aggression, mockery, and hate?

It’s a part of the puzzle, but today’s harassment is a blended phenomenon. Yiannopoulos’ behavior parallels a case I discussed in Reading the Comments where prominent people created a “free speech” forum within which they insulted a woman while anonymous trolls and haters did much worse. I called this a trollplex: an attack by a spectrum of people, from identified to anonymous, exhibiting varied behavior—from jokes to insults to threats—but who share a target, culture, and venue for attack. It’s not possible to lay the blame at one person’s feet, but the target of the harassment suffers nonetheless.

In response to the harassment campaign against Jones, Twitter released a statement, saying, in part, “We know many people believe we have not done enough to curb this type of behavior on Twitter. We agree.” Based on your research, what tools and strategies could social media sites like Twitter employ to combat trolls and limit abuse on a large scale?

Twitter is in a tight spot when it comes to scale. A number of folks noted that when non-celebrities are harassed, Twitter rarely acts upon those reports. Similarly, Yiannopoulos did not tweet much that was explicitly, personally hateful himself. As a celebrity, he could play the part of a trollplex ringleader, directing insults and attention to Jones while playing the innocent and complaining of censorship. So Twitter’s early de-verification and current banning is a symbolic act in a larger struggle, with celebrities as a proxy. But I don’t know what it will mean for the thousands of folks who aren’t celebrities.

Once you have a toxic subculture on a platform, it can be hard to remove it. If Twitter introduced a mechanism to moderate behavior, cabals would quickly create voting blocks to suppress and harass others. I suspect Twitter will continue to increase its policing of harassment, increase ease with which the user can block others, and will perhaps move to algorithmic curation at some point, like Facebook’s feed.

Yiannopoulos censured Twitter’s decision to ban him, saying that “anyone who cares about free speech has been sent a clear message: you’re not welcome on Twitter.” As an author who’s considered the way online comments affect self-esteem and well-being, how do you reconcile the right of internet users to voice their opinions with the emotional damage those opinions might inflict on others?

People also have a right of association. If a platform provider or community decides that it doesn’t want to associate with jerks or tolerate certain behavior, they can refuse to do so. Yiannopoulos can still speak; he’ll still be writing at Breitbart. Twitter’s problem is that this type of curation doesn’t scale well or inexpensively in an open, anyone-to-anyone model. It needs as many users as possible while being a palatable site for advertising. Old broadcasters could do this because they controlled the content they published. Facebook is based on groups and curates by way of its algorithm—the algorithm raises other concerns, but feasibility and profitability is not one of them.