3Qs: When true crime becomes a pop culture phenomenon

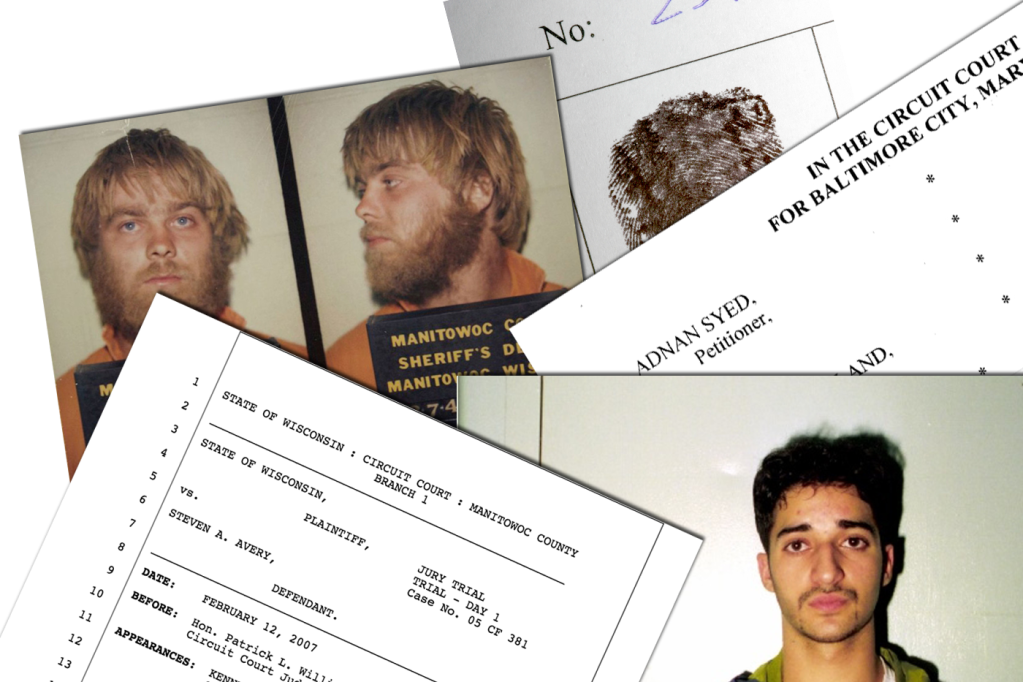

The first season of “Serial,” the hugely popular podcast that debuted in 2014 and has been downloaded 100 million times to date, focused on the case of Adnan Syed, who in 2000 was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. On Wednesday, Syed returns to court for a three-day post-conviction hearing granted by a Baltimore circuit court judge. “Serial,” along with other recent true crime stories such as Netflix’s Making a Murderer and HBO’s The Jinx, have become pop culture phenomena, leading to countless news articles, blogs, and chat room threads dedicated solely to these cases. We asked Northeastern University law professor Daniel Medwed, an expert in criminal law and wrongful convictions, to describe what post-conviction hearings are all about, the prospects for Syed’s hearing, and what has stood out to him most about “Serial” and Making a Murderer.

What are post-conviction hearings, how common are they, and what are the implications of these proceedings?

After a criminal defendant is convicted, the next step ordinarily involves filing a direct appeal with an appellate court—a targeted challenge to what occurred in the case in the lower court. Post-conviction remedies typically refer to other procedural mechanisms—beyond the direct appeal—that are available to defendants after conviction. Post-conviction challenges are often called “collateral” attacks because they tackle convictions from the side, rather than directly, back at the trial level by raising new issues that were not addressed originally. If a defendant raises a legitimate issue through a post-conviction filing, then a trial judge often grants an evidentiary hearing to evaluate the merits of the claim.

Defendants routinely file post-conviction petitions, but the chances of success are slim. In particular, post-conviction hearings are rare, in part, because it is hard for defendants to find compelling new evidence, or new issues, after trial and the direct appeal. There is no constitutional right to an attorney for a collateral action, so many inmates have to proceed on their own. And this, obviously, can be difficult, especially when the defendant remains behind bars. Depending on the nature of the post-conviction procedure, the consequence of a favorable decision is normally a new trial.

Adnan Syed’s post-conviction hearing will reportedly include evidence related to the reliability of cell tower data and a new witness offering an alibi for him. In your view, what are the prospects for Syed’s case?

The key in many cases, like Syed’s, is whether (a) the evidence qualifies as “newly discovered” and (b) whether it is sufficiently compelling to prompt a judge to believe it would have made a difference at trial. If the evidence is what I call “old and cold,” or not central to the case, then it ordinarily is not enough to spur a judge to order a new trial.

In theory, the alleged evidence seemingly supports Syed’s innocence. First, the case was premised on the dubious testimony of the main prosecution witness, Jay, who apparently offered inconsistent accounts about what he and Syed did on the day the victim went missing. Evidence related to the location of certain cellphone calls that day could shed light on the accuracy of Jay’s story. Second, the alibi evidence also calls the prosecution’s timeframe into question. One issue here, though, is whether any of this evidence qualifies as “new.” What did the trial lawyer know about this at the time? My recollection from listening to “Serial” is that Syed’s defense attorney challenged the cellphone data at trial. Has technology improved in the intervening years so that we now could have new insights into the location of those calls? The alibi evidence is tricky, too, if the trial lawyer was aware of it way back when, which means an alternative argument involves ineffective assistance of counsel. It is impossible to predict the odds of success for Syed, but there may very well be enough to warrant a new trial.

Both “Serial” and Making a Murderer have prompted questions of the primary subjects’ guilt. As an expert in wrongful convictions, what has stood out to you most about these two cases?

I must admit to having conflicted feelings. On the one hand, it heartens me that so many people are mesmerized by the topic of wrongful convictions, which has been my primary field of academic and advocacy interest for 15 years. On the other hand, I am dismayed by the manner of presentation in both “Serial” and Making a Murderer. Like many people, I feel manipulated—and this runs contrary to my approach to these cases. I ran the day-to-day operations as assistant director of an innocence project at Brooklyn Law School in New York from 2001 to 2004 and my mantra was to investigate the “paper trail” (read everything) and the “people trail” (talk to everyone) before deciding firmly on the legitimacy of an innocence claim. I tried to remain as objective and detached as possible in this assessment. The non-linear, and arguably manipulative, parceling out of information in these two shows simply rubbed me the wrong way.

That said, I think both “Serial” and Making a Murderer have done a major service by highlighting some of the chief flaws in our criminal justice system, particularly the problem of law enforcement “tunnel vision.” Police and prosecutors all too often latch onto a theory of a case, and beliefs about the identity of the perpetrator, quite rapidly. Once this theory takes hold, it is virtually impossible to convince law enforcement to reconsider their hypothesis, even if there is strong countervailing information. The phrase “first impressions are lasting impressions” is apt—and when it comes to criminal justice, this adage can be damaging indeed for an actually innocent defendant.