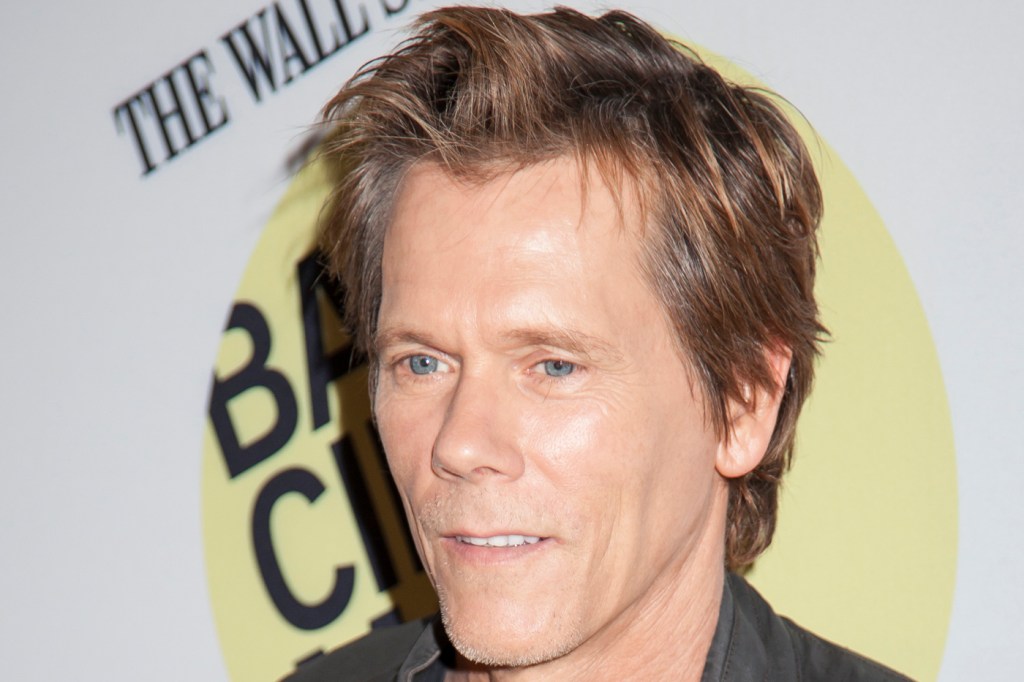

Is ‘Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon’ still valid?

Six degrees of separation. We’ve all heard of the phenomenon. John Guare coined the phrase with his eponymous 1990 play. The theory holds that, on average, each of us is at most six connections away from anyone else in the world. Movie buffs revel in the concept—known in academic circles as the small-world phenomenon—with the trivia game “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon,” wherein players aim to link any Hollywood actor to Bacon through six films or fewer.

But what if the number we’ve all been touting—that neat half-dozen—turned out to be wrong?

According to Albert-László Barabási, Robert Gray Dodge Professor of Network Science at Northeastern, it is and always has been, and no network scientists care.

“Nobody ever thought that the number was accurate,” says Barabási, who heads Northeastern’s Center for Complex Network Research. “But it doesn’t really matter—it could be four, five, six, or even 19. The precise number is a tossup, depending on how dense the network is. What matters is that the number is very small compared to the size of the system.”

The “system” Barabási refers to is any “scale free” network—that is, a network in which the “nodes,” or points of connection, are capable of linking to any number of other nodes. Such networks abound: They characterize everything from the Internet to co-authors of mathematics papers, from Twitter to chemical reactions between the molecules in a cell.

Barabási and his colleagues discovered the rules governing scale-free networks while mapping the World Wide Web in 1999. They found that the Web’s pages, despite the immense scope of cyberspace, exhibited a mere 19 degrees of separation. “Any document is on average only 19 clicks away from any other,” he wrote in his remarkably accessible book Linked: The New Science of Networks. He called the links between the pages “the stitches that keep the fabric of our modern information society together.”

A timeline of papers published on the small-world phenomenon in scale-free networks. The networks characterize everything from the Internet to academic citations, from Twitter to chemical reactions between the molecules in a cell. From Network Science by Albert-László Barabási

My interest in the topic was piqued a week ago when I met with associate professor Dmitri Krioukov to discuss his new paper in Nature Communications, which reveals that the human brain has an almost ideal network of connections over which information zings from one brain region to another.

As a preface to our talk, Krioukov launched into the history of network science.

Hungarian fiction writer Frigyes Karinthy first posited the x-degrees insight (five degrees was his guess) in 1929. But American social psychologist Stanley Milgram brought the concept into the zeitgeist with a 1960s experiment involving person-to-person dispatches of letters from locations in the heartland to two Boston-area residents, one of whom lived, coincidentally (or maybe not—small world, remember), in a suburb south of the city that Krioukov himself calls home. The median number of hands the letters passed through before arriving was 5.5, which rounds up to that ubiquitous six.

However, the latest studies of social networks report an even smaller number—just four degrees—reflecting our terrifically expanding circles of influence. Conducted by Facebook in collaboration with researchers at the Università degli Studi di Milano, the two-part global analysis, which came out in 2011, looked at 721 million active Facebook users boasting a total of 69 billion friends.

Yet despite the shifting landscape (and number of connections within it), Barabási has only praise for Milgram, whom he calls a “pioneer.”

“The importance of the Milgram paper is not the accuracy of its numbers but that this was the first time anyone attempted to do a measurement of this kind,” he says. “He did as decent a job as he could back then. You can’t hold him to the standards of 40 years later, when we know so much more. Everything that has been reported since then is hairsplitting, as far as I’m concerned. The concept is there.”