Last dance with Mary Jane

They call it “getting high” for a reason. The tetrahydrocannabinoid molecule, or THC, contained in marijuana gives its users a legitimate feeling of bliss. In addition to its recreational use, 20 states have legalized the sale of medicinal marijuana, with advocates citing its ability to alleviate pain in cancer patients and bring comfort to veterans suffering from PTSD.

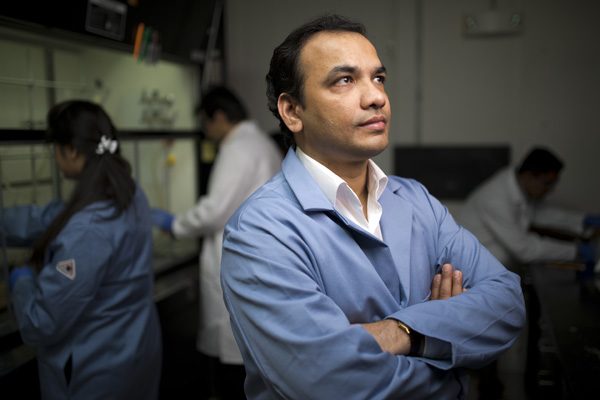

Still, health professionals are quick to note that marijuana has plenty of drawbacks, including its addictive qualities, its capacity to cloud your memory, and its association with binge eating. That’s why Northeastern assistant professor of pharmacy Ganesh Thakur wants to create alternative compounds that have the same medicinal benefits as THC without these associated side effects.

THC, or cannabis, lends its name to the receptors on which it acts. Discovered in the 1980s, the cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2 are located on complex proteins embedded in the cell membranes of some parts of the brain and other organs. When the receptors are bound, the protein changes shape, allowing pleasure-inducing neurotransmitters such as dopamine to pass through.

THC is just one member in a large class of molecules that trigger this phenomenon. There are at least 80 more “endocannabinoids” that naturally occur in the body. Many researchers have focused on developing synthetic cannabinoids that either stimulate or repress the response. But, as Thakur pointed out, synthetic cannabinoids bring with them the same negative side effects as marijuana.

“My laboratory is trying to develop effective and safer medications for treatment of diseases that represent unmet medical needs,” Thakur said. “We work on targets that are validated for certain diseases but drug development hasn’t succeeded because of the side effects.”

While CB1 and CB2 are the receptors through which pot produces its medical and psychotropic activity, the complex proteins mentioned earlier also sport a number of other receptors. These so-called “allosteric” receptors get their name from the Greek words “allos” and “stereos,” which, Thakur said, roughly translate to “other sites.”

When allosteric receptors are bound, he explained, the primary cannabinoid receptors change shape, thereby increasing or decreasing their activity with the naturally occurring cannabinoids.

Thakur said the approach could be applied in a variety of ways. He envisioned the development of a drug that treats anorexia by increasing food-related pleasure without the side effect of addiction. Another potential drug could treat obesity by curbing that desire without causing suicidal tendencies—the main problem with similar drugs that bind CB1 and CB2 directly.

Thakur is also applying his approach to create safer, more effective pharmaceuticals that have the cognition-enhancing effects of nicotine without its addictive properties.

“These are targets that have been validated but have had no success in pharmaceutical programs because of the side effects,” Thakur said. “We’re trying to think of different ways of taking the same target and tuning it to be selective and safe.”