Redefining the ethics of social capital

Patricia Illingworth, an associate professor of philosophy at Northeastern University, says social capital should be understood as a moral good, one in which collaborating across conventional divisions of language, religion and ethnicity could help solve global problems such as war, terrorism and poverty.

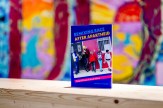

She outlined the argument in a new book, “Us Before Me: Ethics and Social Capital for Global Well-Being,” which was published in February by Palgrave Macmillan to considerable acclaim.

“All truly great leaders — in other words, those who care about people — will find the ideas in ‘Us Before Me’ central to how they frame their local and global responsibilities,” notes Nancy Dearman, CEO of Kotter International.

Illingworth touted the value of social capital at a pair of global conferences in July at Oxford University in London and Sorbonne University in Paris.

She compares her effort to push the moral component of social capital into the public domain to that of an environmentalist focused on promoting sustainability. “To not recycle is now thought of as a moral failure,” explains Illingworth, who holds joint appointments in the School of Law and the College of Business Administration. “We have to think the same way about social capital.”

Viewing social capital as a moral obligation that overrides self-interest, as opposed to a concept of social science, she says, would “lead to greater diversity and increase the likelihood of developing and cultivating the idea.”

And studies show, says Illingworth, that individuals and communities with greater social capital tend to be happier, healthier and safer, in part because of the role social ties play in overall well-being. As she puts it, “There are a lot of things you can do with networks of people that you cannot do on your own.”

But how do you build a diverse social network designed to alleviate suffering and promote global goodwill, tolerance and concern for humanity? For Illingworth, you must start with the individual.

“Social capital has obvious appeal because people are happier with other people,” she says. “Naming it and letting people know about it can have a bandwagon effect and help it slowly become part of the moral parlance.”