Sniffing out a mystery of the brain

A couple weeks ago I attended the pharmaceutical sciences research expo, where, as you might imagine, a bunch of pharmaceutical scientists got together to present their current work. Among a slew of other cool things I learned, I discovered that we have something called the Center for Translational Neuro-Imaging on campus. If you want to get some little creature’s brain imaged for scientific pursuits, Craig Ferris is your go-to guy at Northeastern.

A couple weeks ago I attended the pharmaceutical sciences research expo, where, as you might imagine, a bunch of pharmaceutical scientists got together to present their current work. Among a slew of other cool things I learned, I discovered that we have something called the Center for Translational Neuro-Imaging on campus. If you want to get some little creature’s brain imaged for scientific pursuits, Craig Ferris is your go-to guy at Northeastern.

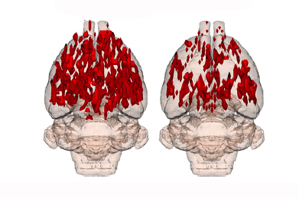

Earlier this year Ferris put out a paper in the journal Behavioural Brain Research about evolutionarily conserved olfactory triggers in rats. His team exposed awake rats to six different smells: almond, banana, rose, citrus, peanut, and “standard rat chow” (doesn’t that sound appetizing?) while scanning their little brains with functional MRI.

They found the results rather surprising. Despite never having been exposed to any kind of nut before (rat chow contains no nuts), their brains lit up like Christmas trees when they smelled either peanuts or almonds and much less when they smelled the other odorants, which aren’t significant sources of calories.

“The finding suggest that the ‘odorant code’ for almond extends beyond the olfactory bulb to include hardwired neural networks conserved over evolution to reinforce adaptive behavior critical for survival,” Ferris and his team write in the article. The hippocampus, which is critical for spatial learning, is activated upon almond sniffing, they write, suggesting that the neural network could allow rats to find food buried or hidden in the environment.

The work has implications for humans and our “innate” love of sweet foods, which are often high in calories and seem to be deeply connected to emotional experiences for some. It would be next to impossible to test the true innateness of our sugar love, says Ferris, because from the moment we take our first sip of milk, we are exposed to carbohydrates. This work shows that in theory a novel odor can activate a neural network in the brain distinct from the olfactory system without ever having learned to love it, indirectly supporting the “sweet literature.”

Anyway, it’s twenty to five and the vending machine on the first floor is faintly calling my name. I must resist.