Published on

96-year-old senior center resident shocks Northeastern Hillel volunteers with an astounding story — her father donated their building to the university

Fay Wilgoren’s father, a 1925 graduate, helped build Northeastern University’s Boston campus. Now, his daughter is sharing his story with a new generation of students.

Julius Abrams was quiet. Unless his alma mater came up.

“He wasn’t antisocial,” Fay Wilgoren, his daughter, remembers. Nonetheless, during boisterous family gatherings she’d often find her late father tucked in a corner, his nose in a historical biography or trade journal. But “things he was interested in — that’s when he talked. And when he talked about Northeastern, his face lit up,” she says. “He was so proud of the campus and being able to go to college. He never thought he’d have an education.”

The son of Lithuanian immigrants, Abrams was a successful developer in Boston and one of the earliest Husky alumni. He graduated with an engineering degree in 1925, when Northeastern University mostly operated out of a YMCA building on Huntington Avenue.

Wilgoren, 96, is telling Abrams’ story from her cozy apartment in Hebrew SeniorLife, an independent living facility in nearby Brookline. Gabrielle Bailey, a Northeastern pre-med student who will graduate a century after Wilgoren’s father, sits next to her, listening.

About a year ago, Bailey and a small group from Northeastern Hillel, the center of Jewish life on campus, began volunteering regularly at the residence. Students attend weekly Shabbat dinners, throw holiday parties and dances and pay social calls. “It’s really special,” Bailey says. “A lot of the older residents don’t interact with young people very often. You see both groups really coming out of their shells, and it shows people in a different light.”

Talking with Wilgoren, a soft yet deliberately spoken woman with wiry gray hair and a sharp memory, volunteers slowly discovered the vast depth of her family’s Northeastern connection. It’s a story that hasn’t been known fully even within NU Hillel itself — until now.

Literally and figuratively, Julius Abrams helped build Northeastern, serving as a cornerstone of Jewish life on campus along the way. As a founding member of NU Hillel in 1962, he bought and donated its first building years later, an abandoned teardown that cost him $1.

When he talked about Northeastern, his face lit up. He was so proud of the campus and being able to go to college. He never thought he’d have an education.

Fay Wilgoren about her father, Julius Abrams

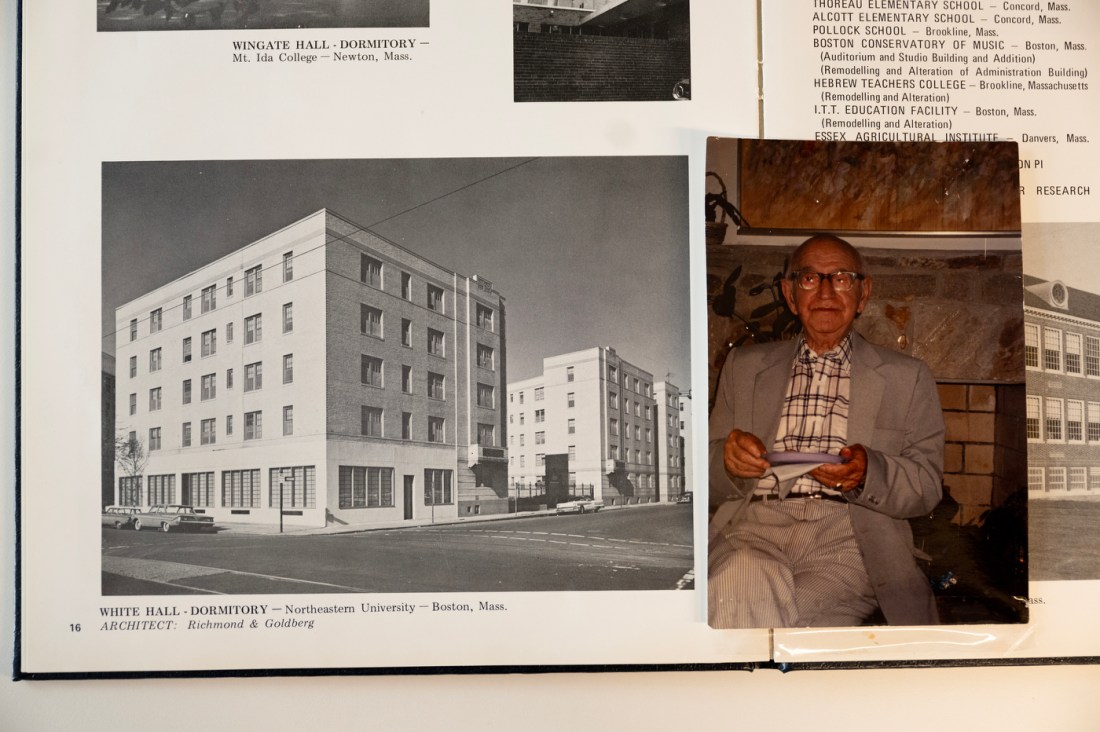

For those familiar with current Boston property values, that’s a story in itself. But as far as Abrams and Northeastern goes, it’s just a tidbit. His footprint is still visible on the Boston campus and beyond — Abrams’ construction company, The Poley-Abrams Corporation, built the White Hall dormitory, the Mugar Life Sciences building and the complete campuses in Nahant and Burlington, Massachusetts, to name a few.

Wilgoren wasn’t a Husky herself (“girls didn’t go to college then” she sighs) but her husband and two of three children were. Her daughter, Natalie, was in the nursing school’s first-ever graduating class in 1964.

Northeastern Hillel rabbi Sara Paasche-Orlow was delighted to learn Wilgoren’s family story. Since she arrived at Northeastern in December (her last position was with Hebrew Senior life, yet another cosmic-seeming connection), Paasche-Orlow has been compiling and unearthing disparate fragments of information from NU Hillel’s early days, slowly building a narrative of its rich history.

“Hillel has this fabulous old double brownstone stuffed with filing cabinets full of documents,” she says. “We desperately need to get more of this history together.”

The timing happens to be ideal. As part of its 100th anniversary celebrations this year, Hillel International — the organizing body for campus Hillel chapters — has been putting out calls for stories from graduates. As a result, Paashe-Orlow has met a who’s who of Jewish Huskies from decades past, including the family of NU Hillel’s first student president and members from the early 1970s.

“People keep coming out of the woodwork,” she says. “I love being the recipient of all these stories.”

Lifelong Husky

Julius Abrams was born in 1902; his family immigrated to Boston when he was a baby, settling just across the Charles River in Malden. His father was a hat maker who designed fur Papahkas for the Cossacks in Lithuania, then uniform caps for sanitation workers stateside. Abrams attended a high school that also operated out of the Huntington Avenue YMCA, then ended up studying civil engineering at Northeastern. As a student, he joined the Kappa Epsilon Phi fraternity and performed in parody shows, sometimes in drag. “I don’t have a picture. I wish I did!” Wilgoren says.

Through the then-nascent co-op program, Abrams worked as a civil engineer in Wellesley when Fay was a baby. He helped design several public works structures still in operation in metro Boston today, including highway overpasses on Route 9 in Chestnut Hill. During the Great Depression, the family moved frequently around the city while Abrams pursued work. As a teenager during World War II, Fay sold war bonds outside the city’s Symphony building, usually sticking around afterward to eat a hot fudge sundae and catch a movie.

In 1945, Abrams founded a construction firm with his partner, Abraham Poley, who Fay called “Uncle Chick.” The company specialized in commercial and educational buildings; its projects, from elementary schools to hospitals, still dot the landscape all around Greater Boston. Some of Northeastern’s most storied buildings — White Hall, the Marine Science Center and the Mugar Life Sciences building — are the work of Poley-Abrams. In 1975, the university awarded Abrams an honorary doctorate in engineering for his contributions.

Along the way, Fay’s father became an energetic Northeastern booster with connections that ran deep. He was close with Asa Knowles, the university’s president from 1959 to 1975; the two even traveled to Israel together. He became a friendly face around campus, too. “He’d walk into the admissions office and try to get relatives’ kids in,” Wilgoren says of her dad.

Listening to the story, Bailey laughs. “I wish I could do that!”

In the early 1960s, decades after he graduated, Abrams brought together a small group of Jewish graduates, floating the idea of sponsoring a campus Hillel. The group incorporated in 1962.

In 1978, he bought a rundown building, 456 Parker St., from the city of Boston for $1. At the time, parts of the city were in serious disrepair, and the local government would routinely take possession of condemned properties, passing them along to developers for a nominal sum. Abram’s company then renovated the building with some financial help from the university. When it was completed, Wilgoren attended the dedication with her grown children. The building was NU Hillel’s home until 2001, when it moved to its current location on St. Stephen’s Street.

Northeastern comes calling

Wilgoren hasn’t visited campus much in the 50 years since. Her father died in 1996; her husband, Louis (another Northeastern engineering graduate) in 2015. But the university would be back in her life before long.

Bailey began volunteering at Hebrew SeniorLife in 2023 as part of requirements for a pre-med application. “But once I started, I really liked it, and that took me by surprise,” she says. “It has changed my perspective about why I want to go into medicine. I like the science and I have always been drawn to that, but this is about how I can serve others and really take care of people.”

She began as part of a weekly nail-painting program, giving out manicures and chatting with residents every Sunday. Gradually, she brought more and more friends from Hillel along to regular gatherings, like Friday night Shabbat dinners, and they started planning more ambitious events.

A highlight has been intergenerational dances, where seniors and college students dress in their best and let loose. In February, the group held a Valentine’s Day dance, decking out the building’s reception hall in pink and red paper decorations and bringing in a live band made up of Northeastern students. By the end of the evening, undergraduates and nonagenarians alike were shaking it on the dance floor.

Deborah Milbauer, a professor in the Bouvé College of Health Sciences, was there with her 93-year-old mother, who also lives at Hebrew SeniorLife. During regular visits to Shabbat dinner and temple services, she also has struck up a rapport with Wilgoren, who, like her father, is always happy to talk about Northeastern.

“I couldn’t believe the connection,” Milbauer says. “She has so many amazing stories going back decades.”

For Bailey, her visits to Hebrew SeniorLife, and becoming close with residents like Wilgoren, have made her college experience simultaneously broader and more intimate. “Since I started volunteering there, I feel intrinsically linked to the city, to the people in the city and to the city’s history,” she says. “I really feel like a part of the community.” One of the relationships she’s forged is with a resident named Rachel, a 106-year-old Yugoslavian immigrant who survived the Holocaust.

Those types of connections represent a fleeting opportunity to gather stories on the verge of being lost to history — unless, as in this particular case, someone is there to hear them. Paasche-Orlow says that is certainly true for NU Hillel, whose youngest founding members are now in their 80s. “We are actively looking to bring together alumni from different periods and begin to create community through that,” she says.

She’s become close with the family of the late Norman Gulko, Northeastern Hillel’s first student president, and had coffee chats with the daughter of Al Frager, a former trustee and the namesake of the Frager House, NU Hillel’s current building.“It’s an age [during which] people are reflecting back on their lives and finding meaning,” Paasche-Orlow says. “They’re seeing this as something important that they did.”

Schuyler Velasco is a Northeastern Global News Magazine senior writer. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X/Twitter @Schuyler_V.