Published on

Northeastern’s first Black fraternity celebrates 50 years — and looks to the future

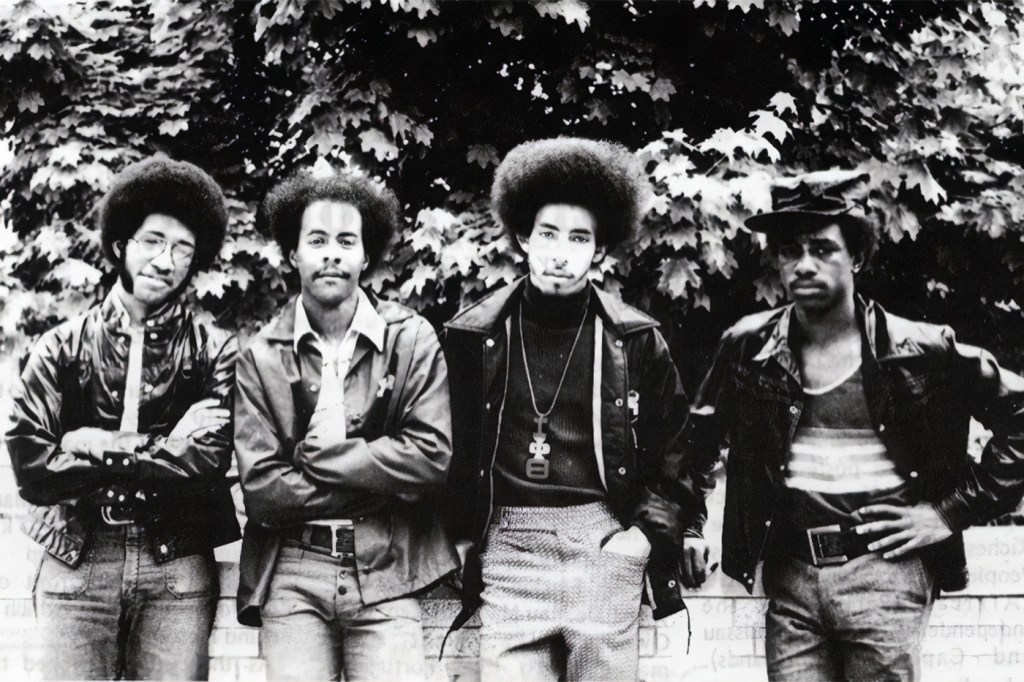

Forged in the unrest of the civil rights movement, Iota Phi Theta’s Omicron chapter helped the university’s Black students find purpose and community. Founders hope to extend that tradition to a new generation.

In the summer of 1974, Boston had reached a boiling point. A judge’s ruling compelling the school system to desegregate — busing Black students to majority white neighborhood schools and vice versa — was fueling riots across the city. Opponents of the plan besieged City Hall and neighborhoods impacted by the ruling, including Roxbury, near Northeastern’s Boston campus.

Amid the chaos, a newly formed band of brothers stepped in to help. Many escorted Black women attending the university back to their dorms against the backdrop of the violent protests elsewhere in the city. Another, the late John Glenn, was a part-time school bus driver in Southie, completing his routes as rocks shattered the windows and rioters swarmed the road. “It was a tumultuous time in Boston,” recalls Shelley Stewart, who graduated in 1975. “Organizing was important, for ourselves and the community.”

They were, and are, founding members of the Iota Phi Theta’s Omicron chapter — the first Black fraternity at Northeastern University. Forged in the social unrest of the civil rights movement of the 1960s and ’70s, the global fraternity is a storied institution in Black higher educational circles, with 300 chapters and 50,000 registered members across the U.S. and as far flung as Japan and South Korea. In its heyday, the Northeastern chapter counted some of the most illustrious members of the student body as “Iotas” — Division I athletes, activists, college radio DJs and members of student council.

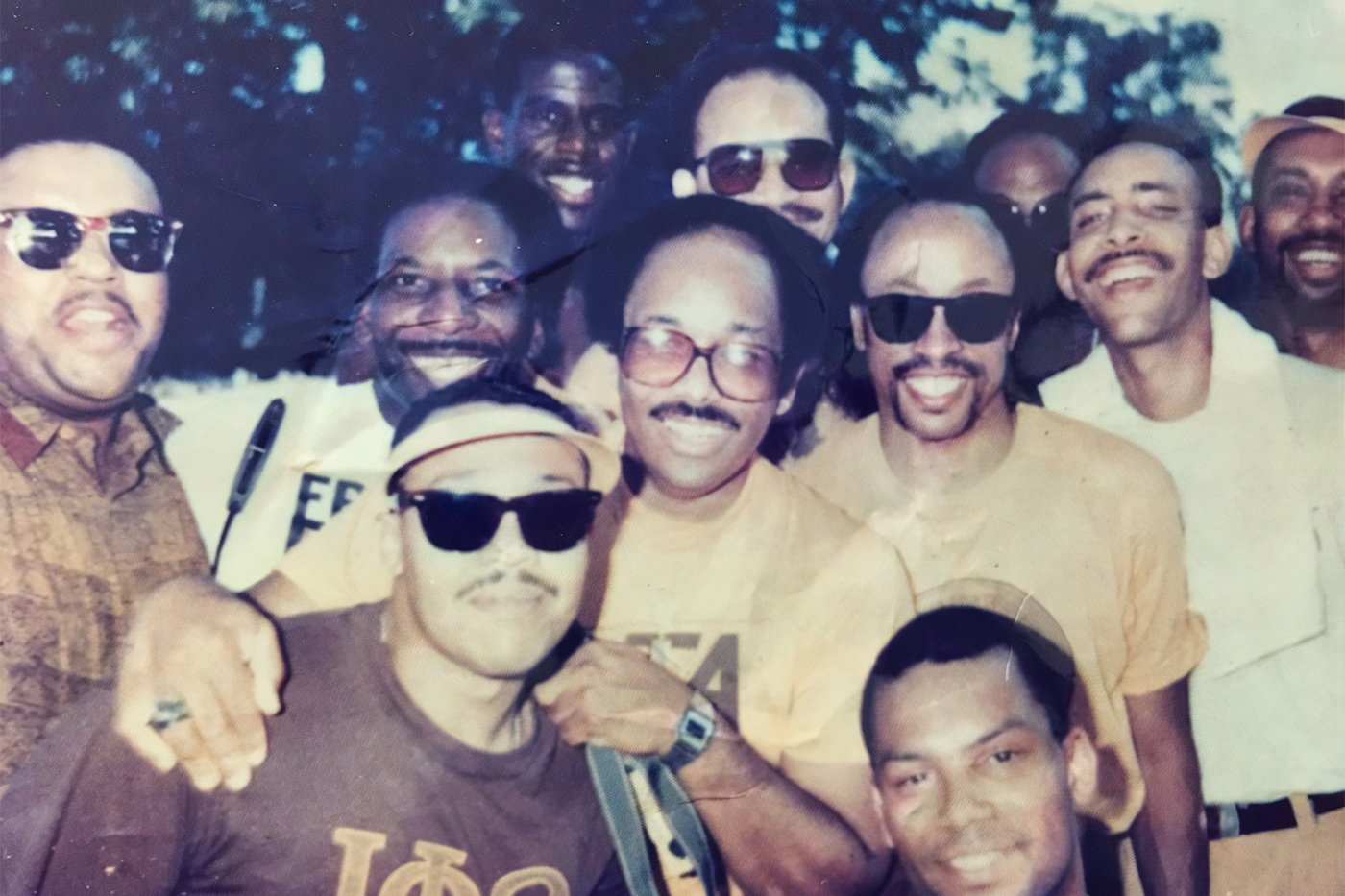

On Sept. 22, the Omicron chapter will kick off a weekend of celebrations for its 50th anniversary, with members from the past five decades coming to the John D. O’Bryant African American Institute on Northeastern’s Boston campus to reconnect and swap stories from their Iota days. They’re also hoping to revive the Omicron chapter. Thanks in large part to the COVID-19 pandemic hampering recruitment efforts, there have been no Iotas at Northeastern since 2019. But past members think there is a vital place for the fraternity in the university’s future.

“It’s a reclamation project for us,” says Keith Motley, a former president of the Omicron chapter. After graduating Northeastern, Motley went on to become the university’s dean of students in the 1980s and, later on, the first Black head chancellor of UMass Boston. He hopes that the anniversary celebrations will pique the interest of potential pledges. “We want to build enough capacity that we can have people go back to campus and help the organization thrive.”

More mature students

The first Iota Phi Theta chapter was founded in 1963 at Morgan State University in Maryland. It has roots in the militaristic strain of the civil rights movement. Many early members were involved in the Black Power and Pan Africanism movements; the organization credits Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael among its early influences.

From the beginning, Iota was more an extension of the surrounding Black community than a closed-circuit college brotherhood. Many founding members were older students, juggling families and jobs along with their studies. “Our organization was founded by men who were going to school at night,” Motley says. “They came into this notion of fraternity in a different way … they were more mature.”

That was true of Jimmy Martin, who graduated with an engineering degree in 1976 and was a part of the Omicron chapter’s second class. Before enrolling full time at Northeastern, Martin took night classes while working a job putting together electronic parts for a company in nearby Norwood. “At first I wasn’t interested in [joining],” he remembers. “I had just switched from working full time to school full time, and I was trying to focus myself.” But he had friends in the founding class, and the excited chatter about the new fraternity around campus was hard to ignore. Years later, he became a “grand Polaris” — top officer — of the national Iotas organization from 1984 to 1990.

For Martin, membership in the fraternity doubled as a history course. He went to a predominantly white technical high school in Boston, where he says he “wasn’t necessarily taught a lot about Black history,” and the turbulence of the civil rights movement in the South was seldom discussed. “I learned more about that at Northeastern.”

The university’s African American Institute, which served as a home base for the Iotas before and after the fraternity’s formation, “had loads of that information,” he says.

Through the fraternity, he also became connected to Iotas in the South and at several HBCUs, where Greek organizations were — and remain — a big part of Black university life. “They are a staple of the Black community,” says C. Hawkins, the director of student engagement and advancement in Northeastern’s alumni office. “Outside of the church, the Black Greek organizations are next.” Iota Phi Theta is a member of “The Divine Nine” — a storied group of fraternities and sororities that counts luminaries including Vice President Kamala Harris among its ranks.

Hawkins, who is working with founding members to plan the anniversary celebrations, says that many Black students who attend predominantly white universities get scholarship support from the Black Greek community. When he arrived on campus as a freshman at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, they were among the first to greet him. For Black first-generation college students, he says, Greek organizations offer “a guaranteed niche of people who understand what that’s like.” Plus, “they throw the best parties on campus.”

The Omicron chapter was part of a larger push to bring those benefits to students in the northeastern United States, and founding members devoted a lot of time and energy to expanding the fraternity to other campuses. On the weekends, Martin says, they would pile into Glenn’s school bus for road trips, recruiting and going to events at schools in several states. Within a year and a half of the Omicron chapter’s formation at Northeastern, Boston College and American International College in Springfield, Massachusetts, had their own Iota chapters. Omicron’s first pledge class in 1973, called the “Lost Colony” line, had 33 pledges, including five students from Boston University (Pi Chapter). A second round of pledges had Omicron up to 73 members by the end of the academic year.

Irving Bell, a civil engineering graduate in 1977, was part of that second group. “At the end of my freshman year, I recognized something was missing in my social life at Northeastern,” he remembers. The Iotas “provided a great social outlet,” and financial aid through the fraternity “allowed me to focus on my studies without the constant pursuit of fellowship opportunities,” he says.

The Iotas’ expansion coincided with a relative surge of Black enrollment in the university system, thanks to affirmative action. Motley and Stewart were a part of that influx. Stewart, from Long Island, was a Martin Luther King scholarship student, the first of his family to go to college. Motley was a highly-touted basketball recruit out of Pittsburgh, just 17 when he stepped onto campus. In 1968, Northeastern had about 100 Black students; by 1970, it had grown to 500.

At Northeastern, the Iota ethos remained one of engagement with that wider Black community. “Most of us were already active on campus,” Stewart says. The Lost Colony line contained football stars, a sizable portion of the basketball team, student government officers, and several students who worked at Northeastern’s college radio station, WRBB. Martin co-hosted a programming block called “Souls’ Place,” which featured music and discussions with Bostonians and local officials about issues affecting the Black community. Stewart had a DJ slot from 7 to 9 p.m. on weekdays, playing music as “Sly from the City.”

‘Natural organizing mechanism’

The Iotas didn’t have a residence on campus — Stewart lived in White Hall during the first few years of undergrad, and Motley lived in Smith. But they say they more or less lived at the African American Institute, founded a few years before.

“The history of the Institute was one of student activism, and the Greek organizations were a big part of that,” says Richard O’Bryant, the Institute’s director. “There was a natural organizing mechanism, so when we had student protests trying to get an issue addressed,” like the divestment from apartheid-era South Africa in the 1980s, “it was Greek organizations that were at the helm.”

Today, the Institute is also the steward of the Brutus “Skip” Wright scholarship fund, named after an Iota who drowned the summer after the fraternity’s founding. Funded in part by Stewart and his wife, Anne, as well as other members and the fraternity’s national office, the fund has given out close to 30 financial awards to Black Northeastern students with good academic records and demonstrated community involvement. For Stewart and his fraternity brothers, it’s a way to give back to the university and brotherhood that shaped the trajectories of their lives. Stewart graduated from Northeastern with a bachelor’s and a master’s in criminology, and went on to a successful career as a supply chain executive; he’s now an active donor and graduate. As an engineer, Martin worked overseas for major defense contractors including Northrop Grumman. Motley is an iconic figure in Boston higher education circles; this past spring UMass Boston renamed a residence hall after him. He’s also in Northeastern’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

In celebrating the fraternity’s origins, the three men hope they can extend its benefits — the network, financial support, and lessons in basic adult skills like organizing events and conducting meetings — to a new generation of Huskies.

“It’s a core part of my college experience,” Stewart says. Not to mention, he met Anne (a charter member of Alpha Kappa Alpha, the first Black sorority at Northeastern) while in the fraternity. They’ve been married 41 years. “The people I met during those times have become lifelong friends — since I was 19 years old.”

Schuyler Velasco is a Northeastern Global News Magazine senior writer. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X (formerly Twitter) @Schuyler_V.