Published on

After Trayvon Martin case, this attorney wanted ‘to make the world better’

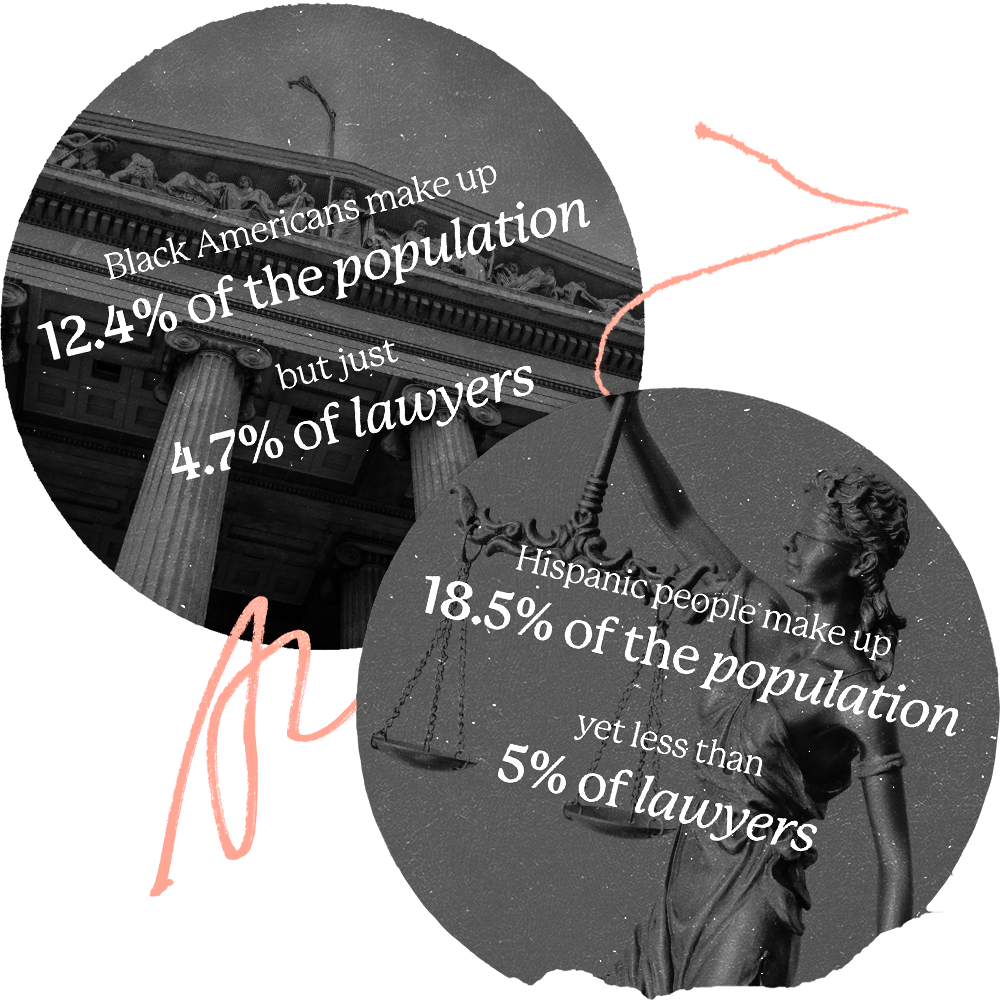

Northeastern University School of Law graduate Kellie Ware has dedicated her career to making the legal profession more diverse. Black Americans make up 12.4% of the population, but just 4.7% of lawyers.

For one little girl, Kellie Ware had to be seen to be believed.

After graduating from Northeastern School of Law in 2018, Ware took a job with Neighborhood Legal Services, representing residents facing eviction, homelessness or other housing issues in Pittsburgh, her hometown. While working with one client—a young Black woman like her—the client mentioned that “her 6-year-old did not believe her lawyer was a Black woman,” Ware remembers.

So Ware rescheduled their next appointment so the client could bring her daughter along. “She’s like, ‘Are you really my mommy’s lawyer?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I’m going to do my best,’” she says.

In the years since, the goal of Ware’s career has been dispelling that 6-year-old’s doubt on a broader scale. She’s working to increase diversity within the legal profession, by making a career as an attorney more accessible for a broader swath of the population, including people of color, those who have disabilities and people who identify as LGBTQ. “It’s really hard to be it if you haven’t seen it,” she says. “I want all kids to think they can do whatever they want at 6, at least.”

In pursuit of that, Ware, 38, has worked as a policy analyst in Pittsburgh’s city government and at the local chapter of the NAACP. She now serves as the director of diversity, equity and inclusion for the Allegheny County Bar Association, where she heads up programs to give law students from underrepresented backgrounds a boost at the start of their careers—through summer clerkships with local courts, trainings, affinity groups for attorneys of color, and social events.

“We want to give you a leg up,” Ware says, “because diverse law students, generally speaking, don’t know as many lawyers to get that first connection for that first job.”

This morning at her home, she’s getting ready to take a group of LGBTQ+ law students to a Pittsburgh Pirates game, part of the bar’s Pride Month celebrations. This is no stuffy networking event: she’s dressed for the occasion in a sky-blue T-shirt, a chunky magenta cardigan, thick-framed cat’s-eye glasses and rainbow chandelier earrings. Her dog, a chocolate-colored mutt named Barry (for Barry Allen, The Flash), putters around in the background.

It’s Ware’s professional prerogative to make people feel comfortable, and to dispel the notion of lawyers as some inaccessible, rarified group. She’s also working to upend it as a statistical reality. In the broader push for a more equitable U.S. justice system, increasing the ranks of attorneys who look like their clients—and share their experiences—is a crucial yet often overlooked piece of the puzzle. According to the American Bar Association, Black Americans make up 12.4% of the population, but just 4.7% of lawyers. Hispanic people are about 18.5% of Americans, yet less than 5% of lawyers.

“And think about the greater number of touches that people of color have with the judicial system,” Ware says. “Thirty-three percent of incarcerated folks are Black. Even if 12% of lawyers were Black, that still means most are not being represented or prosecuted by somebody that looks like them.”

Ware was primed for a law career early, and for working in public service practically from birth. Her mom was an elementary school teacher, and her dad left a career as an executive at AT&T to become a pastor. Her older brother, an artist in New York, hosts walking tours of sites in Manhattan that played key roles in Black history, including the Colonial-era slave trade. “I never really thought about being corporate,” she says.

A big fan of TV courtroom dramas like “Law and Order” and “The Practice” while growing up, Ware was a theater kid in high school and excelled in mock trial competitions. “In Pennsylvania, at least, we had our mock trials actually in the courtrooms, judged by attorneys, and it was a really cool experience,” she says. “It planted this seed that this is something I’d be good at; the preparation was not that different than preparing a monologue for a play.”

Diverse law students, generally speaking, don’t know as many lawyers to get that first connection for that first job.

Kellie Ware, a Northeastern graduate and the director of diversity, equity and inclusion for the Allegheny County Bar Association

Seven more years of school, however, felt daunting. So after graduating college in 2006, she took a job in community economic development, eventually working as a judicial assistant for a family court judge in Pittsburgh. She had two children. Then, in 2013, George Zimmerman was acquitted of murder in the killing of Trayvon Martin, and she felt like she had to do more. “At that time, my son was 5, and I felt that I hadn’t done everything I could to make the world better for him. Two years later I was at Northeastern.”

Allison Wolfson, with whom Ware worked in Pittsburgh, was an NUSL alum and recommended she check it out. “Everyone hated law school, but I didn’t,” Ware recalls Wolfson telling her. “I had a kindergartner and a second grader, so I didn’t want to have a miserable experience,” Ware says.

While visiting campus, Ware was drawn to the co-op program, the slightly older average age of the law students she met “and the idea of being surrounded by other social justice-oriented folks. Obviously, it’s not everybody, but it’s significantly more than you find at your average law school.” When she spotted coffee mugs scattered around the building that read “Make Love, Not Partner,” it sealed the deal.

Once there, she found NUSL more than lived up to that first impression.

The atmosphere was a perfect fit, but also a welcome training ground for Ware to hone the skills needed for a career in bringing different groups together. She did four co-ops, including stints at the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project and the Immigrant Justice Clinic, led by professor Hemanth Gundavaram. “We had projects where not everyone would get along, and not everyone would be on the same page,” Gundavaram says. “[Kellie] did a really wonderful job of being a leader and making sure everybody felt like they were part of the team, but still productive. She’s also just funny, and that helps break tension and make people feel comfortable.”

Ware needs all of those skills and experience for her diversity, equity and inclusion work with the Allegheny Bar. There are myriad obstacles in the way of a more diverse legal workforce — some big and obvious, others small and sneaky, all constantly on her mind.

“It’s baked in at every level,” she says. “In addition to even being able to bear a six-figure debt to become an attorney, bar associations can check out sealed criminal or juvenile records. As part of character and fitness requirements, they’re looking at your credit, outstanding parking tickets, collection accounts. They’re reviewing any criminal history you may have.” This process, she says, is stacked against candidates of color from low-income backgrounds. “We know who’s overly policed, who’s overly prosecuted.”

She adds that in the United States, with its history of slavery and institutional racism, law school can be emotionally difficult for people of color. “You’re discussing things like why you were considered three-fifths of a person when the Constitution was enacted. You have to power through that.”

She thinks a few steps could help. On the policy level, programs that encourage would-be attorneys to work for nonprofits and the public sector in exchange for student debt relief may lessen financial burdens and drive more law students of color to represent their communities. Lowering the high fees for LSATs and bar exams could help, as well as altering the requirement for bar exams to be taken in person. Onerous character and fitness requirements—where old, low-level offenses can be enough to disqualify a person from becoming an attorney—could be more intentional and specific. “What are we trying to figure out by looking at the juvenile background of a potential lawyer?” she asks.

At the Bar Association, Ware’s office serves as a networking outlet for lawyers working on local causes to connect with others who share their backgrounds and life experiences. That sort of identification is vital for attorneys from diverse backgrounds to succeed. Her long-term goal is that the law profession will be open enough that it truly looks like the country it represents.

“I would like to work myself out of this particular job,” Ware says.

Schuyler Velasco is a Northeastern Global News Magazine reporter. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on Twitter @Schuyler_V.