Published on

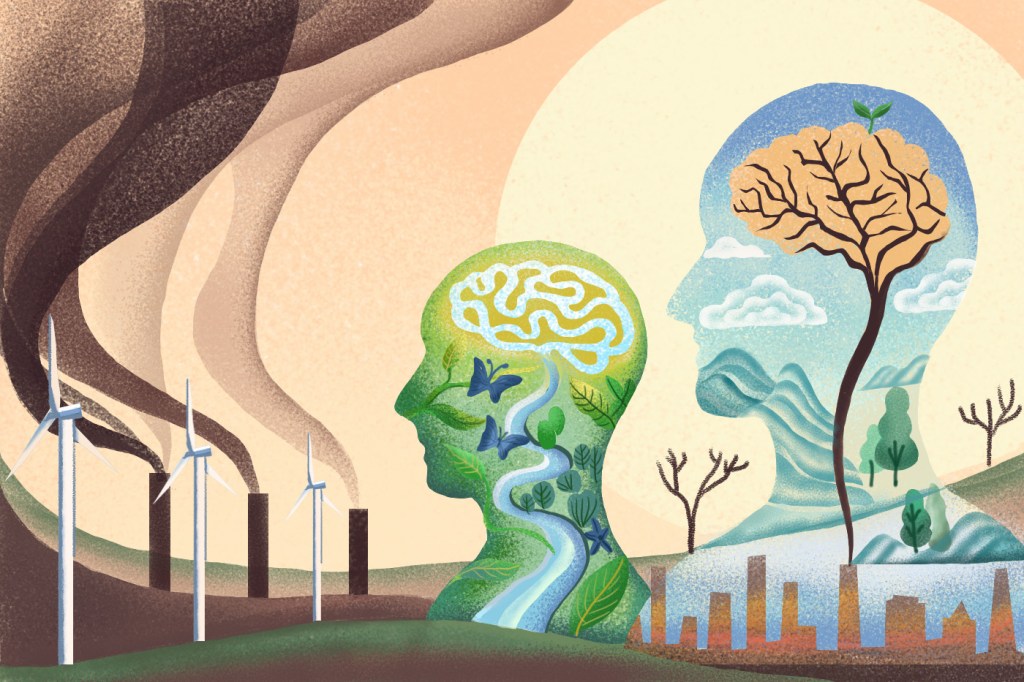

We can’t combat climate change without changing minds. This psychology class explores how.

PSYC-4660: Humans & Nature is part of a broader academic push at Northeastern to explore the intersection of environmental science and cognitive processing — and how it can lead to tangible changes.

When Northeastern professors John Coley and Brian Helmuth tell their students to “introduce themselves,” they really mean it.

It’s a clammy Monday afternoon in mid-January, and the 15 members of PSYC-4660 Humans & Nature: The Psychology of Social-Ecological Systems on Northeastern University’s Boston campus are taking turns in front of a projector. They’re going through detailed PowerPoint slides outlining their majors, family backgrounds, college resumes thus far, hobbies, dogs and cats. Some grew up going to grandparents’ farms and camping every weekend in rural New England; one works part time for a company that sells carbon credits. Eshna Kulshreshtha, born and raised in California, talks about the small arguments she and her Indian immigrant parents have about recycling.

“I’ve never had a class where we spent an hour just doing introductions,” says Kulshreshtha, a second-year marine science major, in an interview a few days later.

In another context it might be oversharing; here it has a point. The central argument of the class is that our personal backgrounds, behaviors and resulting worldviews may hold the key to saving the planet.

A new offering for the spring 2024 semester, PSYC-4660 is a seminar in cognition, a subset of psychology that covers how people encode, represent and process information from the environment in the brain, according to Coley, a psychology professor with a dual appointment in environmental science. Humans & Nature zeros in on how those things inform our interactions with the natural world, and the in-depth intros underscore just how different those can be from person to person based on their backgrounds.

Cataloged as an upper-level psychology class but available to any interested undergrad, the seminar is also part of a larger push at Northeastern to explore the relationship between brain and environmental sciences, including collaborative research papers and a new Ph.D. program currently accepting applicants for the coming fall.

“I have become more and more convinced that this is a critical component to getting people and, honestly, agencies and governments to act in a more sustainable way,” Coley says.

The human behavior side

A marine science professor based at Northeastern’s Nahant campus, Helmuth researches how climate change impacts coastal ecosystems. He has spent a large chunk of his career underwater, and more of it than he would like watching many of those ecosystems disappear. In his view, many solutions to issues affecting the planet are clear-cut; how to effectively implement them at scale is another story.

“In most environmental problems the issue is not the science,” he says a few days after the class meeting. “We’ve got a lot of solutions. It’s the human behavior side that’s hard to change. In policy, there’s a lot of experimentation, but it’s kind of trial and error.”

Coley is a developmental psychologist by training; early in his career, he researched how very young children categorize the natural world. “The first big study I did at Northeastern looked at kids from across Massachusetts — from inner-city Boston and Somerville to some very rural places in Western Massachusetts — and how [their] experiences led to differences in how kids think about relations among plants and animals,” he says. Further research examined how those backgrounds affected college kids’ learning in biology and other life science classes.

In most environmental problems the issue is not the science. We’ve got a lot of solutions. It’s the human behavior side that’s hard to change.

Brian Helmuth, professor of marine and environmental sciences

The two initially met through Nicole Betz, a graduate student in Coley’s lab. Last year, the three co-authored a paper on how human exceptionalism — the idea that humans are different and set apart from other organisms — can hinder sustainable behavior.

Humans & Nature is a further exploration of that type of academic research in a classroom setting with readings, lectures and a heavy emphasis on class discussions, all dealing with questions about how we think comes to bear on biodiversity preservation, food systems and climate change, according to the syllabus.

For the first few weeks, for example, the course content focuses on biodiversity conservation, or preserving the richness of species on Earth. An academic paper by sustainability scientist Thomas McShane explores the trade-offs between preserving biodiversity and human well-being; another, from 2019, explores possible links between a richer array of species and increased mental health in humans. Research from 2016 by a trio of ecologists in the academic journal “Global Environmental Change” focuses on urban biodiversity, outlining possible ways to marry development and conservation of natural environments in an economically equitable way.

The class is not proscriptive: “I don’t think there are specific misconceptions that we’re trying to puncture,” Helmuth says. “A lot of this is helping the students identify complexities” in their different worldviews as they relate to those topics. “I’d be very surprised, even with a class this size, if they were all at the same starting point.”

Featured Posts

Different attitudes

After introductions, the class breaks into small groups to discuss the assigned reading: a thin textbook called “Human Dependence on Nature: How to Help Solve the Environmental Crisis” by Haydn Washington. They talk together at length about collectivism and the sense of community in small, rural villages around the world and how it contrasts to the individualist, comparatively isolated routines of Western European and American societies.

“We can follow a behavior but not value it in the United States,” a student muses. “I think it’s harder. In other societies where [people are more immediately affected by] the general health of their community, it might be easier to implement a belief in sustainability and helping the world around you.”

The conversation isn’t just geopolitical. It’s a group in their early 20s, and millennials catch strays for being off-trend and having a collectively dire outlook on global warming. “I recently saw a video that was like ‘Stanley cups are over because the moms have gotten to it … now it’s not cool,’” one student says. “We’re getting sick of things a lot faster, and overconsumption speeds up.”

“There’s a shift in our younger generation that’s more inclined towards an understanding and appreciation for nature, which was lost on the millennial population because there was so much talk about climate change and overconsumption that everyone got overwhelmed,” says another.

Kulshreshtha has experienced these types of vast differences in attitude even within her family. She grew up frequently visiting relatives in New Delhi and Noida in India. There, she explains, sustainability and eco-friendliness aren’t talked about nearly as much as they are in the United States, but not because people don’t care about it. Rather, sustainable habits and practices are more baked into daily life.

“Especially now, in the United States, people constantly pushing you to think about, like, ‘Hey, make sure you’re recycling the right thing,’” she says. “That’s always on the forefront of your mind — is this thing I’m doing environmentally friendly?”

“With my extended family, it’s not something that they talk about, but they’re not being as harmful to the environment in their daily lives,” she continues. “My family in India still gets milk delivered every morning from the milkman, they put the bottles outside again every day. If you get groceries, you’re not getting individual plastic bags for your broccoli and carrots. The street food vendors use bowls made out of leaves and wooden utensils. All these things are already integrated into Indian culture, so it’s not like you have to be actively thinking about how much plastic you’re using every day.”

Further examination

Helmuth and Coley both think those types of insights can have direct impacts, particularly at a place like Northeastern. Environmental psychology with a focus on the natural world isn’t a totally new concept, but tying it directly to human behavior and policy in an academically rigorous way is a next step. The course dovetails with research the two men have collaborated on, with implications for real-world scenarios like science education curricula and aiding the federal government on more effective environmental messaging and policy (Helmuth was a co-author of the White House’s most recent National Climate Assessment, released in November).

In the fall, Northeastern will begin admission to a new Ph.D. program in Human Behavior and Sustainability Sciences that integrates traditional core requirements of psychology and environmental science graduate programs. The hope is that this sort of interdisciplinary training could lead to more collaborations like theirs. “Someone in psychology who [specializes in] decision-making and someone who studies salt marsh restoration could work together,” Coley says. “We want to provide Ph.D. students with structured opportunities to make those connections across fields.”

And they’re optimistic about the future possibilities those collaborations could lead to. “One advantage of teaching someplace like this is that these students are going to take over the world,” Helmuth says. “We already have a lot of students through co-ops working in the city of Boston, in state offices, at NASA. Anything we do in a classroom here is going to multiply itself.”

Schuyler Velasco is the campus & community editor for Northeastern Global News. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X/Twitter @Schuyler_V.