Published on

The future of prosthetics is 3D-printed. This student has a hand in it

Isabela Castillo began building 3D-printed prosthetic hands as a high schooler in Mexico City. When she came to Northeastern University, she and her friends turned the project into an engineering club with big ambitions.

All universities work hard to attract students. But it’s difficult to imagine a more compelling sell than the one Northeastern University gave Isabela Castillo.

In the spring of 2021, Castillo had been accepted to Northeastern, but she was still deciding on a U.S. college when she and her parents visited campus from their home in Mexico City. “It was a last-minute decision to come, and we couldn’t get a tour,” Castillo remembers. “We were standing in ISEC alone, looking up at the building. And suddenly Joseph Aoun was there.”

The Northeastern president had been passing through the campus’s Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Complex, and he began peppering Castillo with questions. “‘What are you doing here?’ ‘Where are you from?’ ‘What do you study?’” she recalls. She said she was interested in bioengineering. Aoun grabbed his phone and called up Lee Makowski, the chair of the bioengineering department.

Before she knew it, Makowski was giving her a personal tour of the engineering school. “I was shocked,” she says. “Like, I have to come here.”

When she enrolled the following fall, Castillo brought along a project she had been tinkering with in Mexico. Stuck in her house during the COVID-19 pandemic — which closed Mexico’s schools for much longer than in the United States — she began building prosthetic hands.

In the two years since, the project she started alone in her childhood bedroom has grown into Give a Hand, an engineering club at Northeastern devoted to developing low-cost, custom prosthetic hands, primarily for children, using 3D-printed materials.

Castillo started the club after her freshman year with Valeria Solorzano, a high school friend and pre-law major, and Paul Maurin, who she met in one of her first engineering classes. At first, they worked on a donated 3D printer in the middle of Solorzano’s apartment floor. The club now has about 70 members and access to the makerspace in the EXP research complex on the Boston campus.

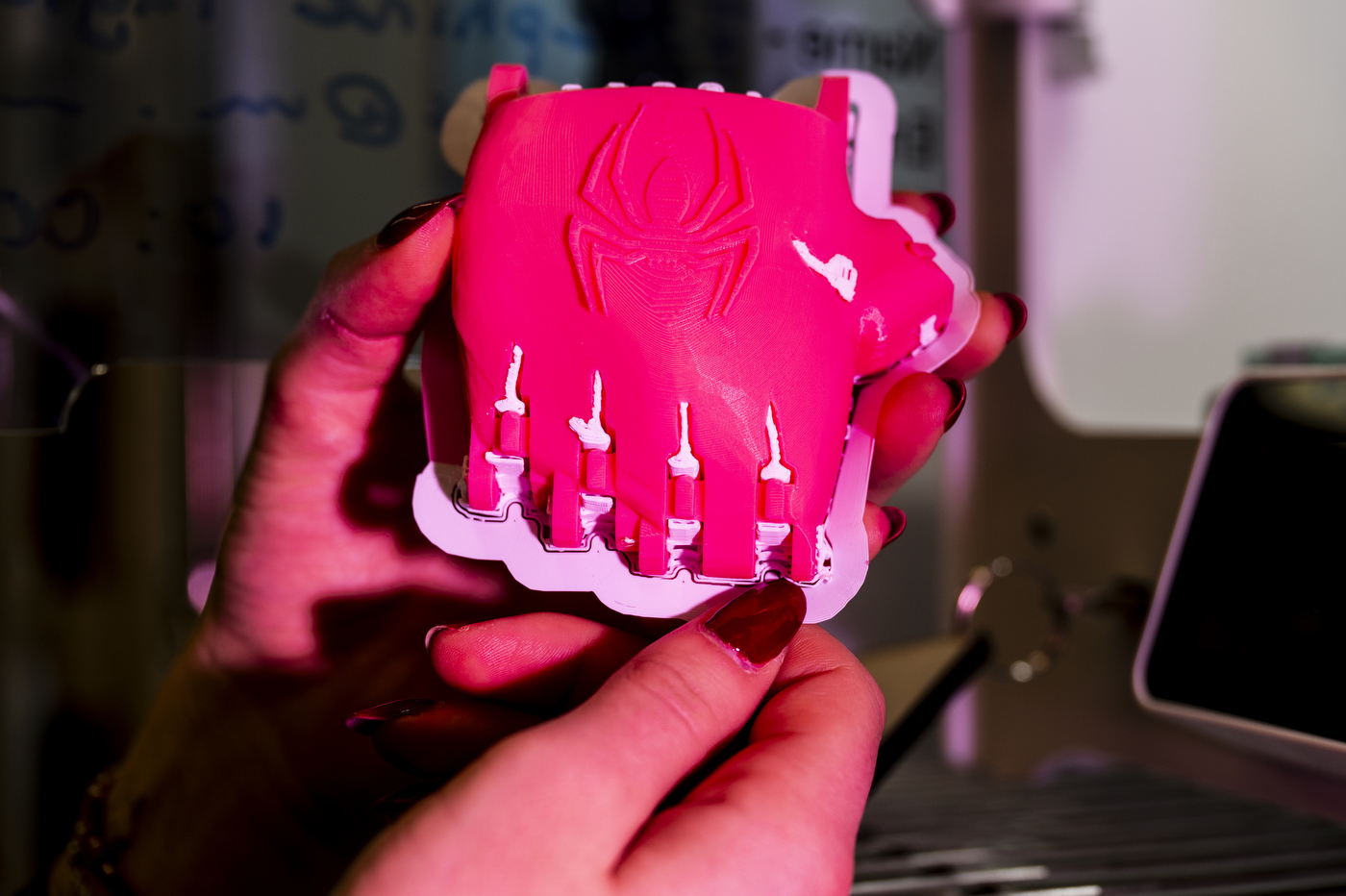

There, in between wrapping up her last week of classes in December, Castillo demos a prototype hand that fits over the wrist. It’s pink and purple, sized for a child in mid-elementary school; a Spider-Man design is etched on the back of the palm. The wrist attachment, palm, articulated fingers and joints are fresh from one of the printers in a dedicated room in the makerspace.

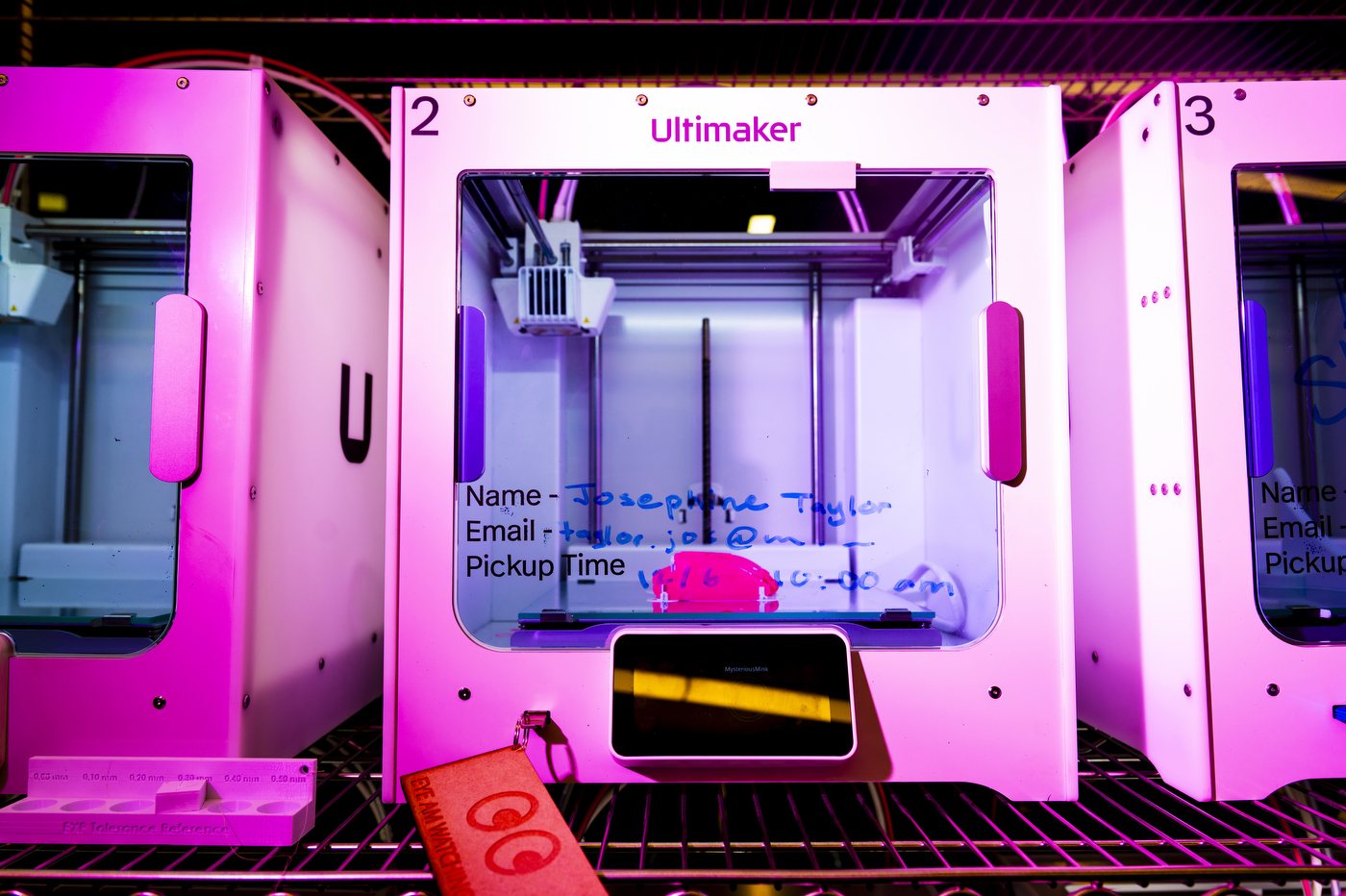

The printers, which look like small farm incubators, are stacked on metal shelving, humming away at projects labeled in dry-erase marker on their glass doors. Working off a computer blueprint, a 3D printer can manufacture a hand’s component parts from plastic filament in about 3 to 8 hours’ time, depending on the design. Castillo then puts them together manually, using metal screws and hand-sewn wire.

On the current market, the cost for a base model fitted prosthetic hand (without any electronics or mechanical capabilities) starts at several thousand dollars. This prototype can be made for $50.

Give a Hand has already made prosthetics for a few children using open-source blueprints from e-NABLE, an online network for creating 3D-printed hands. But the club’s mission is more about proof of concept — developing the hands themselves, but also figuring out how to get them to patients at scale with the buy-in of the broader medical community.

And though that is still a long-range prospect, the club puts Castillo and her clubmates at the forefront of what Makowski — a faculty adviser for Give a Hand — calls “absolutely the future” of biomedical devices. With 3D printing, it’s possible to make precise, custom tools for a range of medical uses, from mobility aids to instruments for complex surgeries, for a fraction of the cost.

“It’s very easy with the computational tools we have now to design for the anatomy of each individual person,” Makowski says. “We’re all different shapes, and to be able to customize is great.”

A change of plans

Castillo first saw a 3D-printed prosthetic hand on display at the London Museum of Design during a family vacation. She was so fascinated by it that she decided to build one for a school project, using an e-NABLE plan. A family friend who was a physician put Castillo in touch with the recipient of the first hand she built, a 5-year-old in Mexico City named Paola. “She’s still using it,” Castillo says.

Her plan growing up had been to go to medical school in Mexico. But building hands piqued her interest in bioengineering, and she started applying to programs in the U.S. At Northeastern, she has found an environment that has lived up to that first auspicious meeting with Aoun and Makowski in ISEC.

“Northeastern gives you what you ask for,” she says. “You just need to ask. I told one of my engineering professors I needed a 3D printer. ‘OK. There’s one we’re not using, here you go.’ And not a basic one, a pretty expensive one. I don’t know that that’s the case at other universities.”

Most of Give a Hand’s members are engineering and science majors focused on research and development. They’re working on projects including a bionic hand with sensors and a 3D filament made from recycled plastic bottles. Another group, led by Solorzano, focuses on the club’s business operations: seeking out funding from the university, attracting new members and finding ways to connect with potential patients.

“We want to reach out to doctors and hospitals, but we want to be recognized in the U.S. first,” Castillo says. Give a Hand is now verified as the Boston chapter of e-NABLE and has had one recipient: a 5-year-old girl in Rhode Island with a congenital hand malformation.

“We’ve made her a couple so far,” says Maurin, who leads the development projects. Maurin thinks that kids (starting around age 5) and low-cost prosthetics are a perfect fit, so to speak. As any parent who’s tried to keep up with a child’s shoe size knows, they grow quickly, making buying typical prostheses a potentially daunting financial prospect. Plus, “kids destroy the hands very often,” Maurin says. “It’s normal; they’re running everywhere, or putting the hands in places where they shouldn’t be. They don’t understand the concept of money.”

Makowski thinks even beyond children, a proven method of producing low-cost prosthetics has the potential to have a huge global impact. “I’m sad to say there’s going to be a lot of need for it,” he says, noting the civilian toll of wars in the Middle East and Ukraine. “With some of the photographs I’ve seen, there are a lot of people who can utilize this right away, and I think it can be done without much technological advance.”

The biggest challenge for a group like Give a Hand, he notes, might be scaling up enough to meet the demand that already exists.

There are a lot of people who can utilize this right away, and I think it can be done without much technological advance.

Lee Makowski, professor of bioengineering at Northeastern University, on 3D-printed prosthetics

‘Absolutely the future’

In many ways, the hands Castillo’s group are developing are emblematic of the broader possibilities offered by 3D printing, which has exploded in both ubiquity and accessibility over the past decade and a half. Though used in specialized industries since the early 1980s, 3D printers first became commercially accessible around 2009; they’ve become gradually more affordable and easy to use ever since.

“It provides the ability to make custom geometries in a much cheaper way than you could before,” says Joshua Hertz, a teaching professor in the engineering school and Give A Hand’s faculty sponsor. “It’s perfect for what this group is trying to do. Without handcrafting the item, you can still create parts that are geometrically unique to the particular shape and needs of one person’s body, from a desktop.”

“For the past 100 years, it’s been cheap to manufacture lots of things if they’re the exact same geometry — that’s the factory mentality,” he continues. “And it was possible to create individualized things with a person crafting it, but there was never anything in the middle.”

There are still kinks to work out before the hands can be a mainstream medical option. They break easily, so the club spends a lot of time manufacturing replacements. One of the development teams is working on ways to make the existing hand blueprint from e-NABLE sturdier.

Castillo says they would like to perfect that prototype, as well as others in the works — including a bionic hand with movement capabilities, a more sustainable 3D filament, and attachments that can allow users to hold tools like forks and pencils — before pitching the devices to U.S. doctors and hospitals. In particular, she thinks if they can develop a low-cost bionic hand for under $1,000, they’d be in prime position to launch a startup.

And Makowski, for one, thinks Castillo and Give a Hand are more than up to the challenge. Students like her, he says, hardly need much advising. “With someone like Isabela, the best thing you can do is to stay out of her way.”

Schuyler Velasco is a Northeastern Global News Magazine senior writer. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X/Twitter @Schuyler_V.