Published on

Biochemist, author, art collector, Soviet émigré. How Vladimir Torchilin became a renowned scientist on both sides of the Iron Curtain

Vladimir Torchilin has lived many lives. The Northeastern University professor shares his story of growing up under Stalin, his meteoric rise as a brilliant young scientist, his journey to the U.S. and the pivotal role art has played throughout it all.

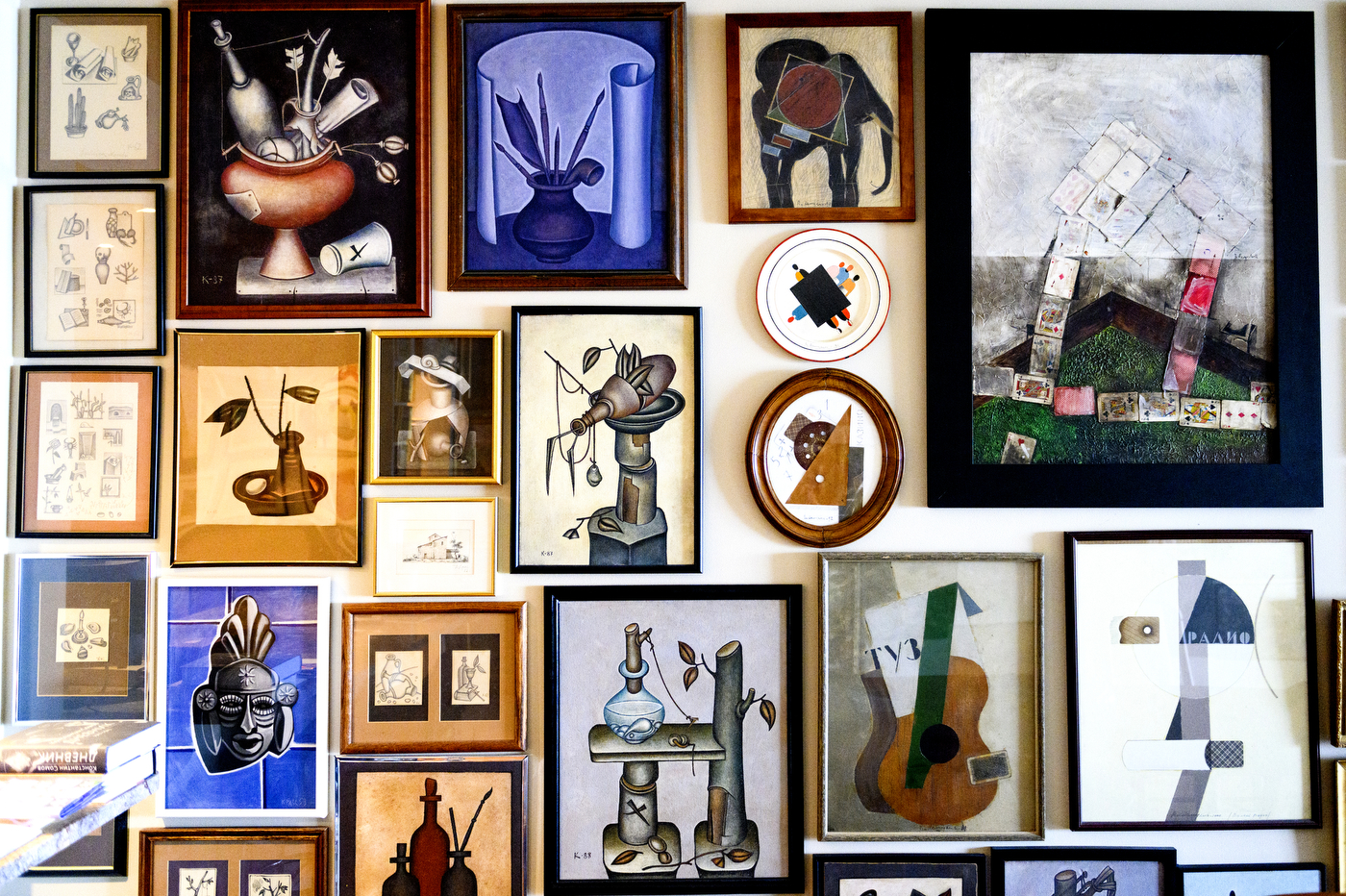

Every wall of Vladimir Torchilin’s Charlestown apartment has a story to tell.

Every inch of the Northeastern University professor’s apartment is covered with paintings, prints, ceramics and lusciously illustrated, artfully bound books. They range in style, age and artist, but most of them are of Russian origin, just like Torchilin.

Each piece of Torchilin’s collection, which, split across his Charlestown apartment and house on Cape Cod, includes close to 2,000 items, has a memory attached to it. A section of his apartment features the work of Moscow underground artist Oscar Rabin, a good friend of Torchilin’s, alongside the work of Rabin’s wife, Valentina Kropivnitskaya, and son, Alexandre Rabin. A glass cabinet along one wall contains plates, ceramics, porcelain and Jewish artifacts that he brought with him when he left Russia with his wife in the 1990s.

“Those small items reflect everything,” says Torchilin, university distinguished professor and director of the Center for Pharmaceutical Biotechnology and Nanomedicine.

The homemade gallery that Torchilin, a renowned biochemist, nanomedicine expert and short story writer, has assembled is rich with history and full of stories. But no story is more interesting than the one Torchilin himself has to tell.

Torchilin recently sat down with NGN Magazine to talk about it all. From his upbringing and groundbreaking scientific discoveries in the Soviet Union to a cleverly executed escape to the U.S., Torchilin has lived a life as dramatic as the paintings that hang on his walls.

Back in the USSR

Torchilin was born in Moscow in 1946 to a pair of art-loving engineers. The Soviet Union and its people were still rebuilding after World War II.

Living under a communist regime came with a guaranteed, if barebones, level of support for every citizen, Torchilin says. Employment, housing and food were all provided by the state, although the quality of each was poor.

His parents were working enough to afford a nanny to help take care of him and his sister. They were not “naked and hungry,” but they were also not living in luxury. The state-provided apartment they received was two rooms, hardly enough for Torchilin, his father, mother, sister, grandmother and nanny. Still, it was better than what most Soviet citizens were used to, he says.

“It was considered to just be outstanding facilities because the sanitary norm for a person was five square meters, which is approximately 50 square feet,” Torchilin says. “You get everything pretty poor but free.”

Still, his parents made space for art and culture in their life, even if Soviet restrictions around certain works, like those of Fyodor Dostoyevsky, made it challenging to access.

“The house was full of books,” Torchilin recalls. “My father and mother were buying a lot of books, so I could read as much as I wanted, and I was crazy about reading.”

Torchilin still fondly remembers his mother taking him and his sister to the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts and Tretyakov Gallery, two of Moscow’s premier art museums. She would also take him to some of the city’s best theaters to see performances rendered by some of the 20th century’s most renowned actors.

In that way, Torchilin says there were many similarities between his early years in the Soviet Union and those of an American youngster being raised at the same time. But there was one overwhelming difference: “a very strong piece of ideology.”

“They talked about Grandpa Lenin,” Torchilin says. “The nation’s father Stalin is much more important than your own father and mother.”

Like every Soviet youth, Torchilin was required to join the Young Pioneers, the Soviet equivalent of the Boy Scouts, where he was taught about “revolution, war, Lenin, how bad capitalism is, how good socialism, how America will die within the next two years.”

“I couldn’t stand it,” Torchilin says.

As Russian Jews, Torchilin and his family faced added challenges in a country run by a secular state. Torchilin’s mother “was not a believer, but she was trying to follow Jewish traditions,” which meant observing certain important holidays like Passover.

In order to celebrate Passover, his mother needed to have matzah, an unleavened flatbread that is integral to the holiday. Given it was a religiously associated good, matzah was not available in state shops. In exchange for providing flour, Jews could get matzah from local synagogues, but it meant running the risk of exposing your faith.

“She couldn’t go there because if somebody would notice her going there, she could lose her job,” Torchilin says. “So, I was going there. Nobody would pay attention to a 9-, 10-, 12-year-old kid.”

He still doesn’t know why, but even from a young age Torchilin knew the propaganda he was being fed didn’t reflect the reality of his world.

When he was 10, Torchilin came home distraught from a Young Pioneer meeting. He told his mother, “I hate it all.”

“She told me, ‘Just don’t tell anybody else,’” Torchilin says. “‘Try to keep as many of those [meetings] as possible without being punished because if you start missing all of them, then you’ll get in trouble. And if you do have some negative feelings, tell them to me and we’ll discuss at home.’”

“I had classical separation of identities, one identity for close friends and family and another identity for school and university,” Torchilin says.

Better living through chemistry

From a young age, Torchilin was attracted to chemistry and the sciences: It was one of the few respites from Soviet ideology.

He was one of the winners of the Union Chemical Olympics, the national high school competition for young chemists, and studied chemistry, with a focus in inorganic chemistry, at Moscow State University. When he arrived in the 1960s, the topic du jour was polymers and the groundbreaking ultra high molecular weight materials that had been created over the last few decades, like nylon and teflon.

“I went to the department of polymer chemists and asked them to accept me,” he says. “I was a second-year student. They didn’t like to accept minors, but I insisted.”

Soon enough he was working on mimicking the properties of natural polymers, proteins, which is where he started entering the realm of biopolymers, including pharmaceuticals and drugs. He graduated summa cum laude –– with a reputation for being a bit of a troublemaker.

After finishing graduate school in 1968, he went to work at the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences under Yevgeniy Chazov, a renowned cardiologist and former minister of health for the Soviet Union. Chazov was also the personal physician for Soviet leaders like Leonid Brezhnev and Yuri Andropov. Chazov’s goal at the time was to build a top-tier cardiological institute in Russia, the National Center of Cardiology, and to do so he was given his choice of location and staff.

“Being a member of the National Academy of Sciences, he made a lot of contacts with academics representing other fields, and he asked them to recommend some young people who he could take and build a network of his own,” Torchilin says.

Torchilin was one of the young luminaries selected by Chazov for the Institute of Experimental Cardiology. Joining the Institute was one of the best decisions Torchilin ever made, he says. He was able to work on creating new methods of thrombolytic therapy, which would go a long way toward helping patients with cardiovascular diseases.

More importantly, Chazov helped Torchilin come to the U.S. for the first time as part of an exchange program for Soviet and American scientists. His life would never be the same.

An American sojourn

In 1977, Torchilin arrived in the U.S. for what became the first of many months-long stints at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The time he spent at Mass General was transformative, Torchilin says.

He developed close relationships with scientists at Mass General, including research physician Edgar Haber. And although he wasn’t blown over by the cultural differences between the U.S. and Soviet Union, the difference between American and Soviet institutions was night and day.

Torchilin was used to the highly centralized bureaucracy of Soviet operations where getting a single chemical reagent could take months. In comparison, everything in the U.S. seemed to move at lightspeed.

“Within three months of staying here, I could do more than at home with the same equipment during a year or year and a half,” Torchilin says.

His work at Mass General was focused on combating thrombotic diseases using thrombolytic enzymes, which, at the time, were known to trigger strong negative responses in patients. Torchilin and his colleagues discovered new ways to modify those enzymes so that they maintained their therapeutic qualities but were devoid of their negative cardiogenic effects. In the process, he and his collaborators at Mass General created new drug delivery systems that could also be used for diagnosing patients, including those with cancer.

“When I started working here on a temporary basis, I understood that I just had to leave [the Soviet Union] because I can do much more as a scientist,” Torchilin.

However, his American excursions came at a cost. His wife and daughter couldn’t travel with him; they “stayed as hostages” to ensure Torchilin, a decorated Soviet scientist, didn’t defect.

After a few trips to the U.S., Torchilin started proactively looking into ways that he and his wife could immigrate to America, a dicey prospect in the Soviet Union.

One visit to the immigration office still stands out in Torchilin’s mind. He expected to face the disdain from immigration officers that had become the norm for Soviet citizens. Instead, the immigration official told him “very frankly, unofficially” to leave with his papers and never come back otherwise he would be in “big trouble.” Torchilin was shocked.

“She said, ‘You have a Lenin Prize, which is the highest national award, and we have the very strict recommendation to under no circumstances allow people with the highest national award to emigrate because it’s a very bad image,’” Torchilin remembers. “She said, ‘They wouldn’t allow you to go anyway, but they will fire you from your job so just stay.’”

Instead, Torchilin decided to bide his time and find the right moment to make his move.

During an exchange trip in the early 1980s, Torchilin discussed the prospect of seeking political asylum with a lawyer he had found. Instead, his lawyer told him to look for asylum as “a life of outstanding abilities,” given his CV and accolades. Later, Torchilin followed his lawyer’s advice and within no time got his green card. But there was still the question of how he would get his wife out of the Soviet Union.

“It was like a chess match,” Torchilin says.

The first move was understanding the peculiarities of how international trips were monitored by the KGB. Torchilin and his wife learned that different departments of the Soviet intelligence agency handled business and private trips, creating an opening for their next move. Torchilin had some of his American friends invite his wife for a private visit.

Then came the third and most complicated move: paperwork.

“If she would write ‘My spouse is currently in the U.S.’ they would never let her go,” Torchilin says. “So, she submitted her paperwork when I already knew I was going to the U.S. [for a conference], but I still was in Moscow, so she wrote, ‘My husband is in Moscow.’ It was absolutely honest paperwork.”

Torchilin flew to his conference while his wife received her passport and took the first available flight to meet him stateside.

By 1991, a year after he and his wife had made their escape to the U.S., Torchilin had started as an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and deputy director and chief of chemistry at the Center for Imaging and Pharmaceutical Research in the radiology department at Mass General.

But seven years later, he made another move. It wasn’t as dangerous or as long as his international elopement, but it was just as significant for his career.

In the late 1990s, former Northeastern President Richard Freeland started contacting Torchilin with an unexpectedly familiar proposition.

“He did kind of the same as Chazov did in the Soviet Union,” Torchilin says. “He went around to places like MIT, Harvard Medical, B.U. and asked young [faculty] if they would like to come [to Northeastern]. … You can see it really worked. Within 20 years, the university completely changed.”

Torchilin joined Northeastern in 1998, where he started working on experimental cancer immunology research through his Center for Translational Cancer Nanomedicine. His work helped Northeastern become the first non-Ivy League school to receive a Center for Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence grant.

“I didn’t regret that I joined the Institute [of Experimental Cardiology], and I didn’t regret that I joined Northeastern,” Torchilin says.

Most recently, Torchilin was recognized as a 2023 Clarivate Citation Laureate, an annual list of likely Nobel Prize winners.

A Renaissance man

Torchilin’s journey has spanned continents and outlasted the Soviet Union. And, like his parents, it’s gone beyond the science that defined his professional life.

On top of his work in biotechnology, nanomedicine and cancer research, Torchilin is also a published author of fiction. He has published nine books, primarily short story collections and novellas, with his first English language book set to publish at the end of this year. His work is inspired by his own experiences as an immigrant but also crosses over into what he describes as “strange stories” (the title of his first book) akin to the work of writers like Edgar Allan Poe.

For Torchilin, his writing is as much of a compulsion –– an itch he needs to scratch –– as his art collecting or research.

“A thought comes to my mind and feels like a shadow,” he says. “Then you start thinking it, and it completely occupies your mind. Just to get rid of it and to allow yourself to do something else, you have to write it down.”

But outside his work as a biochemist, Torchilin is most well-known for his art collection, which has been featured in exhibitions.

His collection started with one elegant, illustrated copy of “Don Quixote,” a volume published by the famous Russian publishing house Academia in the 1920s and 30s. Before he left Russia, Torchilin was one of only a few people in the nation to own the complete collection of Academia’s published books, close to 1,100 volumes. The illustrations in those books were a portal into the art world, which eventually led him to Moscow underground artists like Rabin and the beginning of his collection.

Torchilin says he is not a “real collector” by the standards of some. Unlike most collectors, he doesn’t have a “central axis” for his collection; his walls are covered in a mosaic of art ranging from classic Russian icons to Moscow underground work to paintings from Russian Jews.

“If you are collecting books, for example, from the publishing house of Alkonost, you have to buy all let’s say 30 books they published; I have only 27,” Torchilin says. “[Collectors] ask me, ‘Why don’t you buy the other three?’ I said, ‘I’m not interested.’ Why? Just to put it on a shelf?”

Torchilin’s collection is not defined by any one thing, other than what inspires him and his wife. Torchilin has worn many hats and lived many lives, but at the end of the day, when he settles into the couch at his Charlestown apartment, his floor to ceiling assemblage of paintings towering over him, Torchilin is a collector. He’s a collector of art, certainly, but also a collector of knowledge, history and memories.

“Sometimes when my wife goes to sleep, I just walk around and enjoy this stuff,” Torchilin says.

Cody Mello-Klein is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at c.mello-klein@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @Proelectioneer.