Published on

A Black soldier receives a full military funeral — 83 years after his death. Here is his story

Northeastern’s Civil Rights and Restorative Justice project re-examined a military police killing of a Black soldier in 1941. Eight decades later, the U.S. Army corrected the record to reflect that Pvt. Albert King was killed in the line of duty.

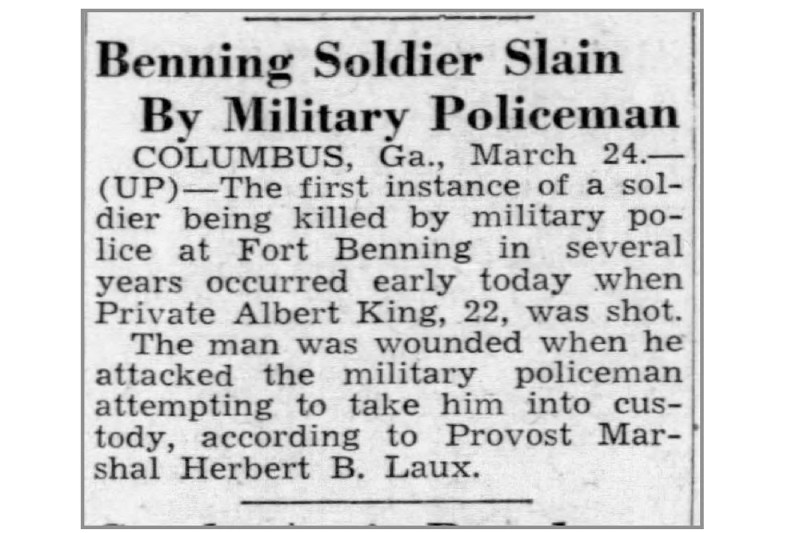

Pvt. Albert King was in his early twenties when he was gunned down by a white military officer in 1941 at Fort Benning, Georgia. For more than 80 years, official military records reflect one version of events: that King, who was Black, was killed as a result of his own misconduct.

That was official history for more than a half-century. That is, until a student and a faculty member with Northeastern University’s Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project (CRRJ) re-examined the case, finding that racism was at play during a confrontation between the Army sergeant and King all those years ago.

With help of several pro bono attorneys from Morgan Lewis, including a 2019 Northeastern School of Law graduate, the Northeastern team successfully petitioned military officials to correct the record, and on March 24, King received a full military funeral — 83 years after his death.

For Micah Q. Jones, a Northeastern law graduate now working in Morgan Lewis’ Boston office, it was a case that hit close to home. An Army captain turned lawyer, Jones had worked on numerous pro bono veterans cases since he started working for Morgan Lewis.

“But I had never advocated on behalf of a deceased client in a case that is 83 years old,” he says. “This is certainly a unique case.”

Jones would help draft the petition put to the Army Board for Correction of Military Records that highlighted the Army’s efforts to cover up the homicide, which was based on extensive research conducted by Northeastern graduate Alexa Mills into King and the circumstances of his death. The complete story became the subject of a magazine piece Mills wrote for the Washington Post.

“This case was full circle for me in many ways,” says Jones, who spent nearly two years at Fort Benning (now Fort Moore) while serving in the U.S. Army. Rose Zoltek-Jick, associate teaching professor and associate director of the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project at Northeastern, was a key player in overseeing Mills’ research, coordinating the legal work and consulting with King’s family. She says it was because of former CRRJ member Tasmin Din that she and Mills were able to tap into the firm’s resources.

But there remained a problem: locating King’s surviving family members. To do so, Zoltek-Jick and Mills turned to yet another Northeastern graduate: Noah Lapidus, a genealogist who works for Ancestry.

“We found Ms. Helen Russell in Detroit, and she agreed to be our petitioner,” Zoltek-Jick says.

Russell is King’s second cousin. When reached, Russell told Northeastern Global News that she was taken aback when Mills first contacted her about his story.

“I was like, oh my God, because I hadn’t known about [King] at all, period,” Russell says.

What followed, she says, was a three-year campaign to clear King’s name. Together, Jones and two other attorneys — in concert with Zoltek-Jick, Mills and Russell — asked the military board to change King’s death record to reflect an earlier determination that he had died in the line of duty.

The commanding general at Fort Benning at the time pushed base authorities to paper over the initial finding, replacing it with another: that King died “while resisting recapture and while attacking” a military officer, according to Mills’ research.

Following a sham court-martial trial — the details of which Mills illuminated in her reporting — the officer who killed King, Sgt. Robert Lummus, was exonerated and sent to a new post at Fort Knox, Kentucky.

When presented with the petition, the board simply reversed course in 2022, acknowledging the injustice and vowing to correct the record. There were no oral arguments throughout the process.

“We were all a little surprised by that,” Jones says. “The Army decided everything based on our briefing.”

In a statement, an Army spokesperson addressed the matter: “The Army puts a high priority on honoring the legacy of all our soldiers and their families, especially when there is an error or injustice, as there was in the case of Pvt. Albert King.”

“What I saw at the memorial ceremony and through my interactions with the Army was that they truly valued this case, and they truly appreciated the opportunity to correct the record,” Jones says. “Just the presence of the base commanding general and the garrison commanding officer at the memorial ceremony showed that the Army really did value this case.”

Mills, who worked on several Jim Crow-era cold cases during her time at Northeastern, learned about the King case while researching a lynching that also occurred at Fort Benning in 1941: the unsolved killing of Pvt. Felix Hall, which is believed to be the country’s first known lynching on a military base. That research was also conducted as part of her work with CRRJ.

In 2021, the Army installed a memorial for Hall.

A representative from the Army reached out to Russell directly to address the error.

“He called me and apologized, and I could feel his emotion,” she says.

“The board had done something it had never done before, and that is to correct the record from that long ago and, moreover, attribute it to racism,” Zoltek-Jick says. “And once the record was corrected, we decided that the next thing that we could or should do for Albert King was get him the full military funeral he never had.”

The vast majority of CRRJ’s archived cases are researched and developed by Northeastern students. The clinic first launched in 2007 under the direction of Margaret Burnham, a lifelong civil rights activist and university distinguished professor of law at Northeastern; the program grew over the years, inviting graduate-level journalism students to participate in case research in addition to law students, Zoltek-Jick says.

Between 50 and 60 cases are completed every year by law students, journalism students and co-op students, among others. Pro bono attorneys from various firms are often involved in cases as well.

Zoltek-Jick says justice wouldn’t have been possible without Mills’ “extraordinary commitment” to the cause.

“Alexa is extraordinary in her commitment to the material that lasted long past her graduation,” Zoltek-Jick says. “The reporting that Alexa did just shows the depth of factual investigation that is needed in order to bring a successful legal claim.”

During the military funeral, Russell was presented with a bronze medal and an American flag. A tombstone to King now reads: “For my beloved cousin, I fought the fight.”

“I was glad to be there, because I fought the fight for my cousin,” she says.

“He had no one really remembering his story,” Zoltek-Jick says.

Tanner Stening is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at t.stening@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter @tstening90.