Published on

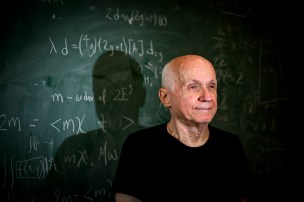

Math can be intimidating — unless your professor is Solomon Jekel

During a four-decade tenure, the Northeastern University mathematics professor has helped his department grow into a flexible, friendly place for students to take their love of numbers in many different directions.

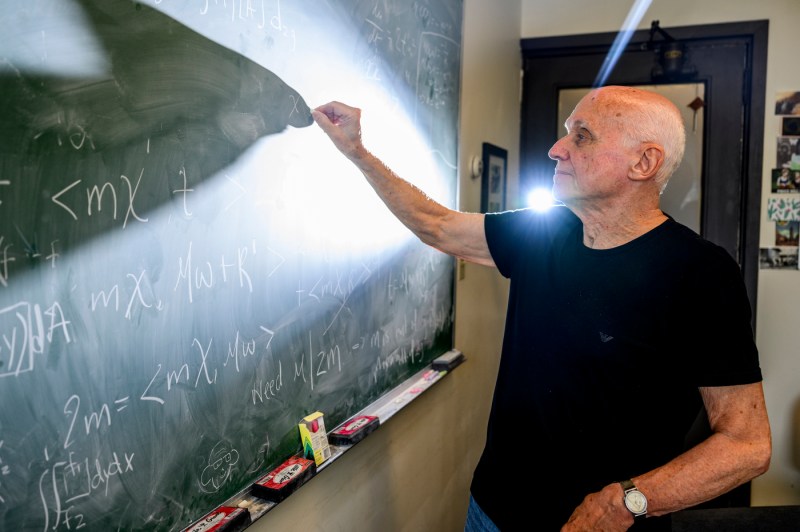

Solomon Jekel has been at Northeastern University for 44 years. There’s a problem he’s been working on even longer.

“It’s such a challenge,” says the longtime mathematics professor, sitting in jeans and sneakers on the couch in his sunlit Boston office in Lake Hall. “Everything I’ve done since then has been because that has been too hard.”

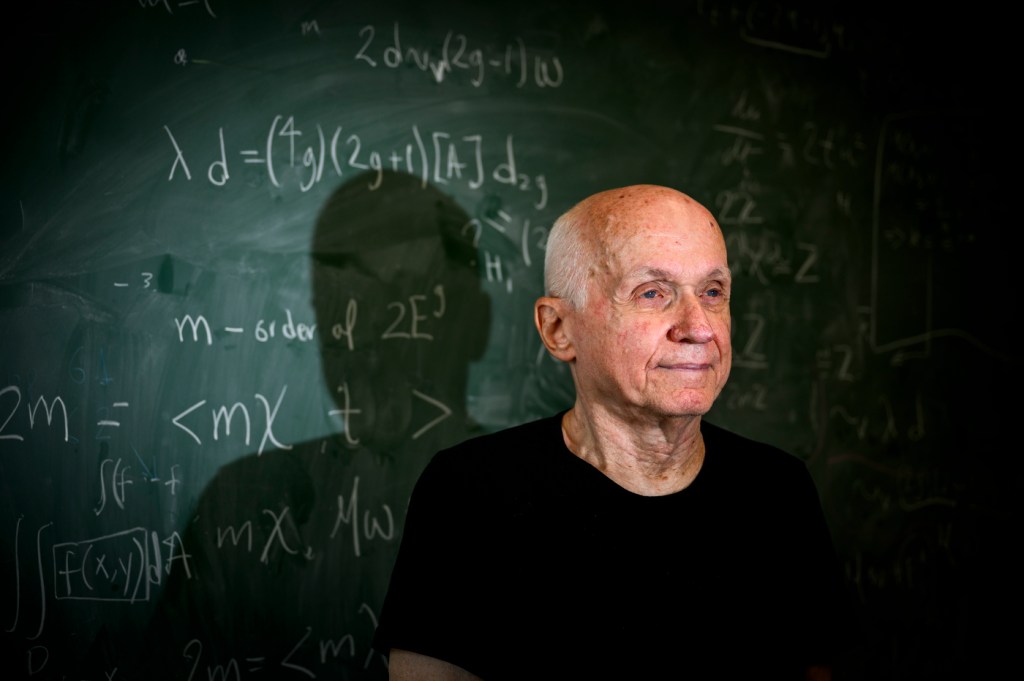

Jekel’s academic specialty is differential topology. For a near half-century, he’s studied the dynamics of moving objects on three-dimensional surfaces. In pure math, these dynamics are called foliations, expressed through differential equations. Jekel’s earliest breakthrough, part of his Ph.D. work at Dartmouth College in the 1970s, involved using algebra (rather than geometry) to understand certain foliations. The findings were a big deal at the time, and published in the American Journal of Mathematics. As is typical of math, however, they led to even more questions.

“One of the problems that arose is the one I’m always working on in the background,” he says. “I still hope to crack that nut. Mathematics evolves that way because mathematicians aren’t just interested in solutions — they’re interested in problems, maybe even more. That’s what keeps us alive.”

Jekel has had plenty going on in the meantime. He’s a respected topologist, with collaborators across the world and visiting professorships in Mexico and in the Netherlands. At Northeastern, as a student adviser in the College of Science, he’s watched the math department grow leaps and bounds — both in terms of its size and flexibility to students’ needs.

“Fifteen years ago, there were 50 math majors,” he says. “Now there are 800. Six hundred fifty of those are combined majors, and I think that’s a real strength of our program. Students who love math can [also] study business, and neither really obstructs the other.”

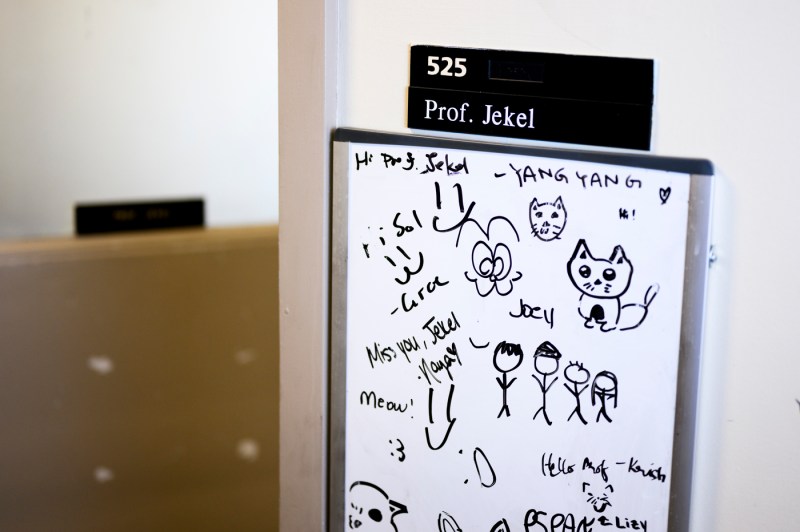

Along the way, students say he’s been an invaluable sounding board and a driving force in cultivating a singularly welcoming campus atmosphere for students who love math.

“He doesn’t take math seriously, and I don’t mean that in a bad way,” says Kimi Nguyen, a fifth-year applied math major. “There are a lot of math departments where it’s very cutthroat, very gatekeeping — people don’t want to allow you to say you’re a mathematician. At Northeastern, I’m very lucky. It’s a community here.”

Jekel chose to spend his life in mathematics not out of any career considerations, but for the perpetual difficulty of it. Growing up in Philadelphia, he thought he might study languages — Jekel’s father was a German immigrant, and he grew up speaking and reading German. His Romanian mother could pick up “a language in a day or two.”

“She went down to Mexico to visit me once and she didn’t know any Spanish, but because Romanian is a Romance language, she just started to talk to people,” he laughs.

But math won out. “The decision was based on what I thought would provide the greatest challenge moving forward and keep me going,” he says. “And it turned out to be true. I’m 76 years old, and I don’t think there’s been one day I didn’t think about math.”

After undergrad at Temple University in his hometown, he earned a Ph.D. from Dartmouth. His thesis adviser, however, was at Harvard, and he fell in love with the Boston area during trips down from New Hampshire to collaborate. After postdoctoral study at MIT and a detour teaching at the Politecnico in northern Mexico, he signed on at Northeastern.

Mathematicians aren’t just interested in solutions — they’re interested in problems, maybe even more. That’s what keeps us alive.

Solomon Jekel, Northeastern University associate professor of mathematics

In the decades since, what it means to pursue a math career has taken on a more flexible definition. Traditionally, Jekel says, math majors have been separated into pure math or applied math tracks — the former pursuing academia, the latter going on to careers in finance and business. But the rise of data analytics and artificial intelligence in virtually every field has blurred those distinctions.

“They’re both important,” Jekel says. “In terms of advising, we encourage students who are not sure to follow both directions — you’ll give yourself more resources looking to the future, and every course will be valuable. [Industries] need sophisticated techniques to deal with [problems] creatively.”

This dimension of math is often overlooked, he thinks. “AI is doing a lot. But what you lose in AI is the creative aspect — trying different approaches to a problem, taking leaps of faith and making mistakes. That process is going to take on increasing importance. It’s not just answers, it’s how you get there.”

The possible interdisciplinary applications, he says, are endless.

“Some [combined majors] are really increasing, like biology and math. I think that’s going to have a very successful future in environmental science. There’s such a future for anybody who wants to work with climate change, for example.”

Featured Posts

As the math department’s faculty adviser, Jekel helps students parse how, exactly, math will fit into their academic and working lives. Nguyen first met him her junior year, when she was trying to find a way to avoid taking a required course that didn’t play to her strengths. “I was trying to get out of Real Analysis. It’s pure math and I hate pure math,” she recalls.

Jekel gently told her she had to take it in order to complete her degree. “I was really upset,” she remembers. “But he said, ‘You know, I believe in you. I see you working in the math lounge, and I know you can do it.’”

He’s been a steady source of support for her ever since — they have tea together in his office every Friday. She’s cried in his office — not the first or last student to do so. With Jekel’s guidance, Nguyen embarked on Northeastern’s Plus One program, earning credits toward a master’s degree in applied math alongside her undergraduate coursework. Both as an adviser and a teacher, Nguyen says, one of Jekel’s big strengths is an ability to make math seem simple.

“The way I learn from him is very easy,” she says. In class, “he’s kind of slow, very quiet. He tells you what you need to know, then if he still sees confused faces, he’ll explain again.”

This summer, Ihunaya Eluwa, a third-year combined math and business administration major, has been in California interning as a financial analyst for Microsoft. But she and Jekel are still in touch. “I haven’t taken a class with him in a while, but I still keep in contact with him,” she says. “He’s reached out during my internship to see how I am.”

Eluwa says Jekel was instrumental in her decision to pursue math as part of her major, crafting a degree track through the College of Science that would allow her to find a place for her love of numbers in the corporate world.

“He’s been a sounding board for me to talk through my ideas,” she says. “His door is always open on Tuesdays and Fridays, so during the semester I’d make it a point to just go in and talk. He’s definitely a safe place for me at Northeastern to talk about things outside of math, outside of college.”

Though he’s still an active and sought-after researcher, Jekel says those student relationships are what keeps him going well past retirement age.

There are a lot of people who are retired and still doing research and conferences, but teaching is like sipping from the fountain of youth, he says. “Students think I’m teaching them, but they’re teaching me. I don’t just look at their grades or how they do on quizzes. I watch how they react to me, how they react to my lectures, how they interact with each other, so I can adapt accordingly.”

Outside the classroom, there’s still that pesky 50-year-old problem to solve. “I’m closer,” Jekel says. “I think I’m going to get it.”

Schuyler Velasco is the campus & community editor for Northeastern Global News. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X/Twitter @Schuyler_V.