Published on

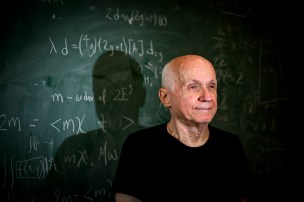

Wendy Parmet became a public health giant. In true Northeastern fashion, it started with a co-op

During her four-decade career, the distinguished law professor has emerged as a leading authority on disability and public health policy in the United States — from AIDS to COVID-19.

Wendy Parmet doesn’t like to talk about herself. She’ll talk about her dog, though.

“This is Noah, that was the name when we got him,” she says, holding up the white, 10-pound toy mix on her lap. “He’s about 8 years old, he’s very cute and he’s the stupidest dog there ever was. Untrainable.”

According to colleagues, Parmet has one of the most diligent, dazzling minds ever to grace the halls of Northeastern University’s law school, where her teaching has won devoted fans and prestigious national awards. Yet despite her best efforts, Noah is tenuously housebroken and never bothered to learn his own name. Last fall, he bolted out the front door of her house in Newton, Massachusetts, ran two miles to a major road, got hit by a car and ran two miles in the opposite direction. Thousands of dollars in veterinary bills later, he still tries to escape at every opportunity.

“There’s no learning there,” she sighs. “But how could you not love this face?”

Listening to the distinguished law school professor talk about her hopeless rescue dog isn’t just an entertaining sidebar; it offers telling evidence of the qualities others praise in Parmet, an accomplished attorney and one of the nation’s leading experts on U.S. public health and disability policy. Fellow faculty describe her as frank, keenly observant and exacting — but also generous, hardworking, modest and a delight to be around.

“I’ve never had more fun working with anyone,” says Jeremy Paul, a professor who served as NUSL’s dean from 2012 to 2018. “If we had more people like Wendy in the world, it would be a better place.”

Parmet has been at Northeastern nearly 40 years. From that perch, she’s become an essential practitioner at the intersection of public health, disability, ethics and the law. She’s worked on landmark cases, helping set legal precedents around AIDS and health insurance for immigrants. A prolific writer, she’s authored three books and dozens of articles in academic journals and mainstream news publications. She emerged as a highly sought media source during the COVID-19 pandemic, arguing for mask and vaccine mandates. As director of Northeastern’s Center for Health and Policy law, she’s helped turn NUSL into one of the nation’s top programs for that field.

“We have an extraordinary health faculty, and she basically built that,” Paul says.

It’s a vast, varied body of work guided by a central legal theory, Parmet says: the idea that improving and protecting health for the most individuals and groups possible should be “the essential goal of the law.”

“Northeastern has given me the ability to go in different directions at different times,” she says. “But this is always what I’ve wanted to do.”

‘My students were older than me’

Like countless Northeastern stories, Parmet’s journey to becoming a giant in the public health law field involves a co-op. But we’ll get to that later. First a quick biography:

She grew up an only child in Queens, New York; her father, Herbert, wrote presidential biographies. As a girl, Parmet loved reading historical fiction and was obsessed for a time with Mary, Queen of Scots. In high school, she co-wrote a rock opera based on Homer’s “Odyssey.” It was never staged.

In college at Williams and then Cornell in the 1970s, Parmet considered pre-med but majored in government. Still, “I remained interested in health policy and health law,” she says. Her senior thesis was on abortion (which “seemed at least a little bit settled,” at the time) and she did two summer internships in Washington, D.C. — one at the U.S. Public Health Service and one with a congressman working on health insurance legislation.

“This was the period between the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid and the announcement of the Affordable Care Act,” she recalls. “The question at that time was [whether] the government was going to expand Medicaid into something like universal health insurance. That was very much in the air.”

After graduating from Harvard Law School in 1982, Parmet worked briefly in corporate law. “I was working on construction litigation, and I found it the most boring thing in the world.” When she joined the law school faculty, she was just 28.

“I don’t know why they hired me this young,” she says. “When I started teaching a lot of my students were older than me.”

At Northeastern, she made her first inroads to specializing in public health and disability law — teaching courses and researching the legal history of epidemics for law review journals.

I’ve never had more fun working with anyone. If we had more people like Wendy in the world, it would be a better place.

Jeremy Paul, professor and former dean, Northeastern University School of Law

‘They change people’s lives’

But her public health work really took off during the AIDS epidemic; as mentioned, it was thanks, in part, to a co-op. In 1995, Parmet took on a young law student named Dan Jackson as a research assistant.

“All I knew about Wendy at the time was she was one of the toughest graders in the school,” says Jackson, now an NUSL professor and executive director of the NuLawLab. “She put students into a sort of combination of revelry and terror.”

As a law student, Jackson’s first co-op was with Boston’s Gay Legal Advocates and Defenders (GLAD) organization, working on the group’s AIDS law project. There, he was assigned to work on Abbott v. Bragdon, a case pitting a dentist in Maine, Randon Bragdon, against a patient, Sydney Abbott, for whom he had denied care because of her HIV+ status. Abbott sued on the grounds that the refusal was in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Parmet, meanwhile, had been researching the emerging intersection of AIDS and disability law and taken over teaching public health law classes. After discussing Abbott v. Bragdon with Jackson, he connected her with his supervisor at the AIDS law project. She joined Abbott’s legal counsel when the case was still making its way through the lower courts.

Eventually, it reached the U.S. Supreme Court, where Abbott’s team successfully argued that the dentist’s refusal amounted to discrimination. It was a landmark case, marking a shift in a collective understanding of the disease and setting a precedent for AIDS victims to be treated as a protected class under the law.

“Abbott” was one of two vital cases on health care accessibility in which Parmet has been involved. The other, Finch v. Commonwealth Health Insurance Connector, ensured access to Massachusetts’ health insurance marketplace for legal immigrants.

Parmet cites those cases as the proudest moments of her career. “They change people’s lives,” she says.

Around the same time, she collaborated with Jackson on a hugely influential article in the American Journal of Law titled “No Longer Disabled: The Legal Impact of the New Social Construction of HIV.” It documented the shifting legal language around HIV and AIDS, which, thanks to treatment breakthroughs, were evolving from certain death sentences into manageable chronic conditions.

“There aren’t a lot of academics out there who invite their students to coauthor journal articles,” Jackson says. “The smartest person in the building was treating me as an equal, which is a really unusual experience in academia.”

Some of his favorite law school memories are of sitting on the floor of Parmet’s office in a sea of case printouts, writing together. “She is hands down the most impactful person in my legal career,” he says.

Editor’s Picks

Salus Populi

Paul says that at times, Parmet’s understanding of the issues facing society has been so clear it verges on the clairvoyant. His favorite example: In 2017 — three years before COVID-19 upended the world — Parmet put on a health law conference at Northeastern called “Between Complacency and Panic: Legal, Ethical & Policy Response to Emerging Infectious Diseases,” focused on pandemics. The keynote speaker was Anthony Fauci.

“It would be hard to predict anything as well as that,” Paul says.

Since those first major contributions to the legal landscape around AIDS in the 1990s, Parmet has brought her sharp understanding and instincts to three decades of shifting public health policy. Her 2009 book, “Populations, Public Health, and the Law,” is considered a seminal text in the field; it argues that courts have a vital role in protecting public health and proposes a population-based approach for legal policy decisions.

Last year, after emerging as a sought-after expert on public policy during COVID — appearing frequently on TV and penning pieces in news outlets including the New York Times and The Atlantic — she published “Constitutional Contagion,” a book making the case that Supreme Court rulings related to COVID have eroded lawmakers’ power to make sensible, science-based regulations during epidemics. It’s an issue she’s tackling off the page, as well. In 2023, she served as faculty co-director of “Salus Populi,” a Northeastern training program to help judges better understand the broad societal factors that affect public health.

“Wendy is willing to say things that other people might be scared to, but she does it delicately and respectfully,” Paul says.

From Parmet’s deeply knowledgeable vantage point, the public health challenges facing both the United States and the world writ large are only growing. Climate change poses huge societal health risks. In her view, the COVID-19 pandemic put regulations like vaccine laws on shakier legal ground — a concerning development, since she also thinks another pandemic is on the near horizon. At times, such challenges seem so daunting that she doesn’t know “whether I will keep going or just go off to my garden and play with my dog,” Parmet says.

Knowing her well, Paul has his doubts. “She really dives into every challenge to try and figure out how we can make things better,” he says. He points out that salus populi, the Latin slogan from which Parmet’s judge training program derives its name, means “the good of the people is the highest law.”

“That sums up all of her commitments over many, many years,” Paul says. “I hope she stays [at Northeastern] for years to come.”

Schuyler Velasco is the campus & community editor for Northeastern Global News. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X/Twitter @Schuyler_V.