Published on

Pran Nath, Northeastern’s longest-tenured professor, pursues the beautiful mysteries of physics

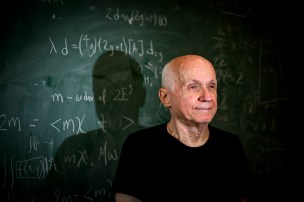

After 58 years, the world-renowned researcher continues to explore the secrets of the universe. His explorations are a mystery to most of us, conducted with a stream-of-consciousness array of mathematical symbols reinforced by terminology that sounds like English taken to the third power.

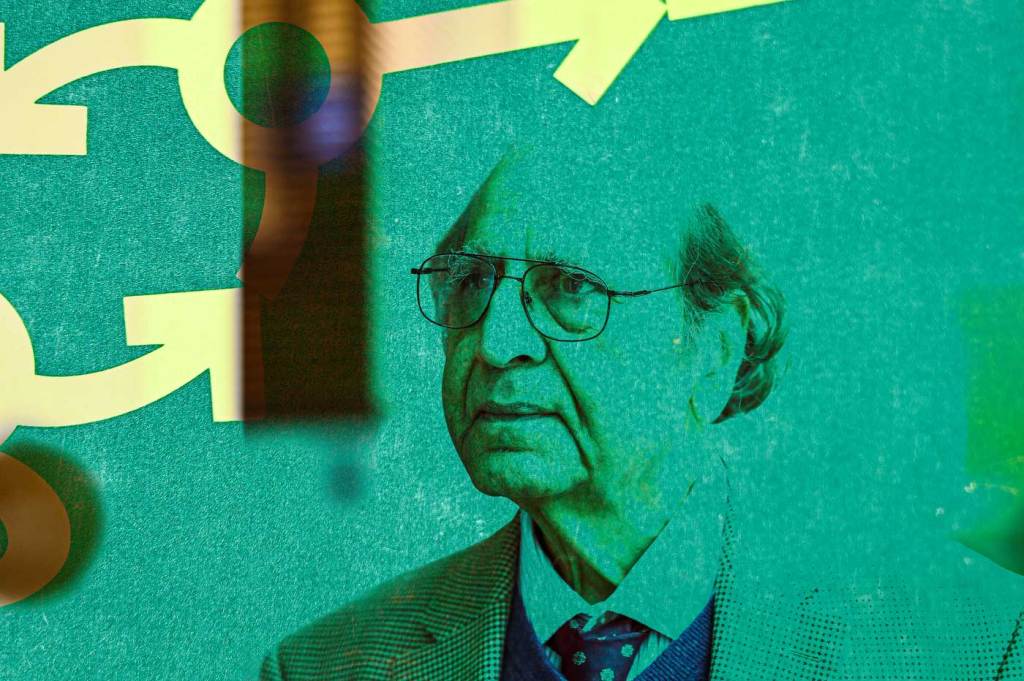

Pran Nath has a humble way of demystifying the secrets of the universe.

“What fascinates me about physics is not just that it is the source of all sciences,” says Nath, the Matthews Distinguished University Professor in physics at Northeastern. “It’s that we understand so little of it when it comes to the big physics question: Why does the universe exist? Of course we know sufficient physics to be able to do the everyday tasks — build bridges, buildings, make cars and electrical appliances and now even microchips.

“But the deeper you dig, the more beautiful physics gets — more intricate and more fascinating,” says Nath, who has lived in the U.S. since emigrating from his native India as a young graduate student. “And with that depth, you open up a vast new unknown and you begin to realize that you understand even less of the whole picture.”

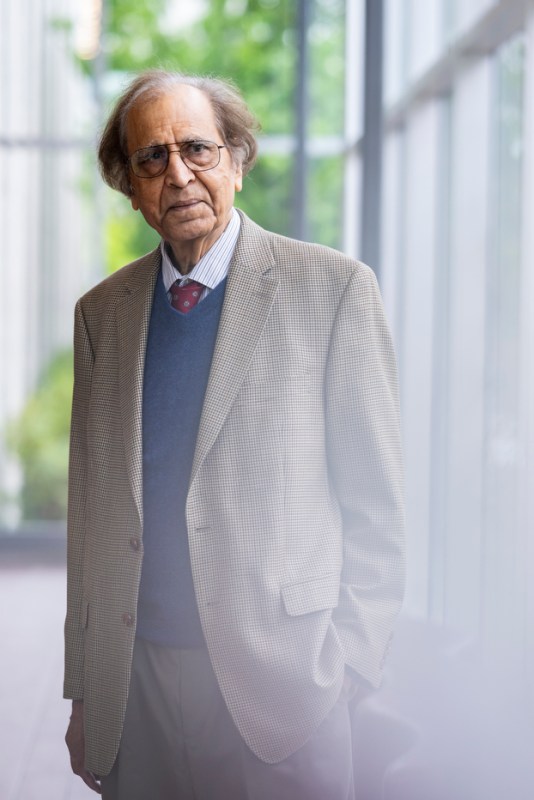

The paradox intrigues Nath. At 84 he continues to pursue research at Northeastern, where he has been working since 1966 as the university’s longest-tenured professor. His explorations are a mystery to most of us, conducted with a stream-of-consciousness array of mathematical symbols reinforced by terminology that sounds like English taken to the third power.

Do not be intimidated by these forbidding appearances, he insists. At the heart of Nath’s lifelong desire to grasp the great beyond is an appreciation for humanity’s limitations.

“Right now we have the standard model of physics, which explains particle physics,” Nath says. “And there is a standard model of cosmology, which is the general theory of relativity by Einstein.

“We put these two together and that explains the bulk of physics and cosmology,” he says. “But there remain important missing pieces to be filled.”

Which is to say — after 58 years at Northeastern — that the work is just beginning.

“But then there are those missing pieces which we don’t understand,” he continues. “They contain the secret of what is next.

“Finding them would open up a door,” he says, enframing his vision with the grin of an enduring optimist. “And once you get in, you will find a whole new world view of what the universe is made of.”

‘Almost a revolution’

The world-renowned professor was born in 1939 in Harappa, an archaeological site in Punjab province that became part of newly formed Pakistan amid India’s 1947 independence from Britain. By then Nath’s family had moved to Delhi, the capital territory of India, where his father served as curator of what is now known as the National Museum in New Delhi.

“We lived in a tent on the premises of the museum,” says Nath, noting that the living arrangements were not unusual for archaeologists like his father. “The museum was in a very central place between the India Gate and the government house where the union ministers and the governor-general lived. I saw these leaders of India’s independence movement in the neighborhood all the time.”

The exception was Mahatma Gandhi, the leader of India’s drive for independence who was assassinated in 1948. Nath’s older brother attended a public event featuring Gandhi. “But I was too young to go,” Nath says.

Nath is grateful to have been raised in an academic environment. His children have benefited in the same way — his son is a mathematician in the City University of New York System (CUNY) and his daughter is a professor at the University of Toronto.

His wife, Shashi Nath, is also an academic who received her Ph.D. from Panjab University in Chandigarh and taught for over 20 years at Northeastern. ”I attribute whatever success or notoriety I have achieved to her toleration of my postdoc-like work habits and standing by me over the years,” Nath says.

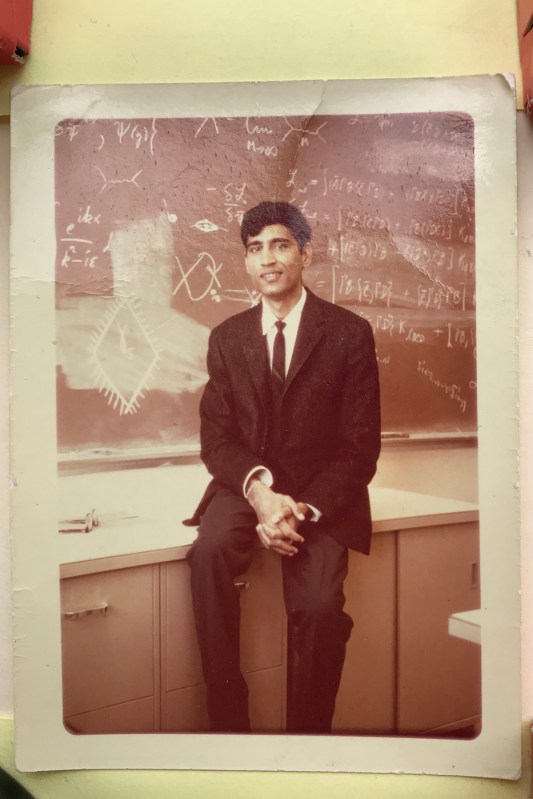

As a young man he moved to the U.S. to attend Stanford, where he earned a Ph.D. in 1964. Northeastern recruited Nath as a professor in 1966, launching a career that is measured by the old-school row of filing cabinets lining the long wall of his office in the Dana Research Center.

“I became a distinguished professor in 1992 — but that’s not why I got this larger office,” says Nath, who entered the new millennium with more paper than his old quarters could handle. “I brought the chairman into my previous office and I said, ‘Look, I have no place to sit.’”

His first impressions of the U.S. were of a country brimming with cars and hospitality. “The Americans were wonderful to me,” Nath says.

He reviews his career with similar wonder.

“It is almost a revolution if you compare what we knew in 1960 versus what we know now in terms of physics,” Nath says. “They are two different worlds.”

Nath helped create the new understanding by teaming in 1975 with Northeastern colleague Richard Arnowitt to develop the original theory of supergravity, which created a new perspective on how subatomic particles are influenced by gravity and other actions of matter. It led to more groundbreaking discoveries.

“Pran is the founder of supergravity unification, a theory unifying gravitational interactions with the standard model of particle physics,” says Tomasz Taylor, a physics professor at Northeastern. “Formulated in 1982, it is still the leading candidate for a theory describing elementary particle physics beyond the standard model. Pran not only invented this theory together with Arnowitt and [Northeastern professor Ali] Chamseddine [currently at American Beirut University], but for many years he worked on its experimental consequences.”

Nath’s unification theory is being tested at the Large Hadron Collider, the world’s most powerful particle accelerator, 100 meters underground near Geneva on the France-Switzerland border.

His research has inspired and been inspired by Nobel laureates.

“The way this world works is that people who come at the very end and put it all together, they basically get all the credit,” Nath says. “But they stand on the work of many, many others.”

This was a lesson he learned initially from his father, who failed to receive proper credit for an archaeological discovery of the 1930s. A half-century later, when Nath was in the midst of his own breakthroughs, Abdus Salam, who shared the 1979 Nobel Prize with Sheldon Glashow and Steven Weinberg for their work on the electroweak theory, advised him that it would be necessary to publicize his work to ensure that he and his colleagues received the proper credit.

“I was complaining, ‘Why do I have to do that? Isn’t it sufficient to do the research? Why must I also proselytize it?’” Nath says, smiling at the memory. “And he says, ‘Well, even Newton had to do that.’ So it is an interesting thing that in every stage of your life you have to do both. It is not sufficient to do the original work, whichever field you are in. There is also the issue of disseminating your findings.”

What good is the work if no one understands it?

“Exactly,” Nath says. “And that actually can be as tough as the work, and sometimes even tougher.”

Communicating with Stephen Hawking

But his love for the science prevails. Nath often volunteers to be interviewed when Northeastern receives media requests for comment on scientific issues, says Mark Williams, chair and professor of the university’s physics department.

“In addition to being a top researcher, Pran has been a wonderful colleague who clearly loves his job as a researcher, faculty member and mentor to students,” Williams says.

“Pran is a very generous person with his time, with his students and with his research ideas,” adds James Halverson, an associate professor of physics at Northeastern. “Speak with Pran for a few minutes and it’ll be clear how much he loves physics, which carries over into his research and collaborations.”

Nath initiated the Conferences on Supersymmetry and Unification of Fundamental Interactions (SUSY), which was held recently in Madrid for the 31st time.

“SUSY is considered one of the most important elementary particle physics conferences,” Taylor says. “Pran is a role model for the next generations of theoretical physicists. He is also well known for his service contributions to the international physics community, in particular for organizing conferences.”

Nath was responsible not only for starting the Particles, Strings and Cosmology (Pascos) conference, but also for inviting to the inaugural 1990 event the famed English theoretical physicist, cosmologist and author Stephen Hawking.

“He came twice,” Nath says. “The second time he invited himself.”

Hawking suffered from a slow-progressing, paralyzing form of motor neurone disease that forced his reliance on a speech-generating device.

“I went with my wife to receive him at the airport,” Nath says. “We were waiting and then suddenly I turned around and he’s there. I couldn’t communicate with him because I didn’t know how to talk to him. His entourage hadn’t told me what is the communication method.

Featured Posts

“Then a passerby recognized him and said, ‘Mr. Hawking, how are you?’ And that’s when I learned that I had to read what he was writing on the screen of the computer connected to his chair.”

In 2019, instead of throwing Nath a grand party when he turned 80, his colleagues gave him a birthday present he would enjoy: a scientific conference devoted to his research into particle physics and cosmology that continues to this day. Nath often wakes up at night to realize he has solved a difficult puzzle in his sleep.

“Nature has some logic by which it does things at an infinite amount of speed,” Nath says. “If you look at the whole universe, how many particles are there? And nature is computing their motion with infinite precision at every moment — and all of it effortlessly.

“The most fascinating thing I find is that our equations have something to do with the actual dynamics of nature. We are using paper and pencil — or computers — for equations which are simulating phenomena in the real world.

“What we have found is that the deeper we go into physics, the more beautiful it gets and the simpler it gets — but that simplicity comes at a certain level which is much more sophisticated.”

He and his colleagues are continuing to dig at the deeper truths, he says.

“The question is, should we ever get to the bottom of it?” Nath says. “Will we ever be able to understand all of physics — including the origin?”

Ian Thomsen is a Northeastern Global News features writer. Email him at i.thomsen@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter @IanatNU.