Published on

How has the sport of rowing evolved in 50 years?

Andrew Neils, a scientist at Northeastern University and a former U.S. National Rowing Team member, details the sport’s evolution, from lighter materials to advancements in blade design.

With origins dating to the B.C. era, few sports have as rich a history as rowing.

In ancient times, row boats were not used for sport, but out of necessity. They were major forms of transportation for many civilizations, including the Egyptians and Romans, and were instrumental in times of warfare.

But in the millennia that have followed, rowing has evolved into a globally recognized athletic activity, making its Olympic debut at the 1900 Paris Games.

Rowers will travel to Paris to take part in this year’s Olympic Games. Among the athletes participating is Northeastern graduate Jacob Pilhal, who will be competing in the men’s single scull event.

How has the sport evolved over the past 50 years?

Technologically speaking, Andrew Neils, a materials scientist at Northeastern’s Roux Institute and former U.S. National Rowing Team member, says the introduction of lighter materials, advancements in blade design and the proliferation of electronic devices outfitted with sensors have been key to the sport’s evolution.

Let’s start with the boats themselves. In the sport’s infancy, racing hulls were made of wood, he notes.

“If you think about the materials that we started with, generally wood is phenomenal,” he says. “It’s fairly lightweight. It’s buoyant.”

Featured Posts

Wooden hulls were a mainstay in competitions until around the 1970s, as composite materials began to be used in place of wood, Neils noted. For as good as wood was, composite materials offered a new way for boat makers to craft vessels that were both lighter and stronger than their wooden counterparts.

In the early days of that transition, hulls were made using fiberglass, he says. Carbon fiber then hit the scene with a number of advantages over fiberglass, offering increased strength while reducing the weight of the shell, Neils explains.

Carbon fiber was more expensive than fiberglass, but costs eventually went down and is now the primary material used to make shells.

“When I started rowing in college back in the early 2000s, I rowed in fiberglass,” Neils says. “Carbon fiber was available, but it was really expensive. Now, everybody is doing carbon fiber.”

That’s just on the materials front, he says.

“The design has probably changed even more than that,” he says, highlighting the evolution of blade designs.

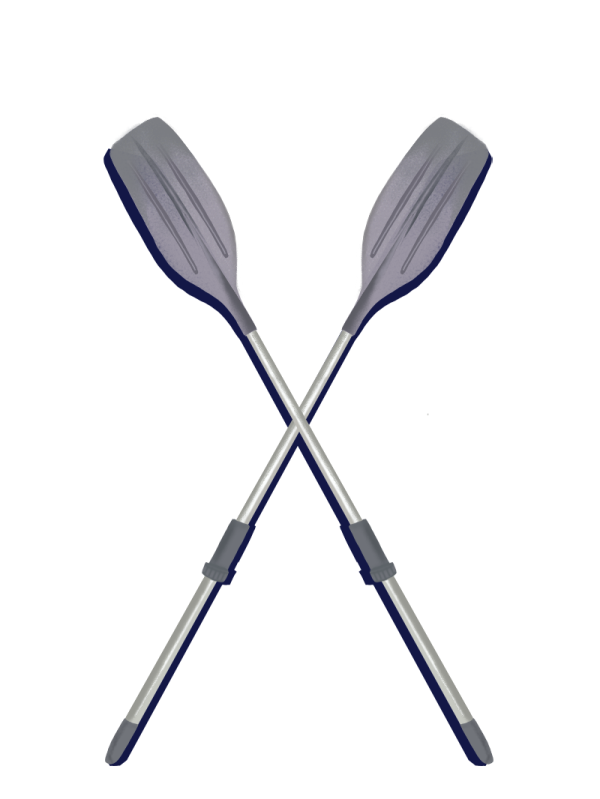

Oars used to feature tulip blades, a type of blade that featured large scoopers that allowed rowers to grip onto the water. But they weren’t the best, Neils explained.

“You don’t put as much load on them, so you don’t get as much grip in the water,” he says.

Since then, blades have gotten shorter and fatter, allowing for rowers to grip onto the water more easily, he says.

“There’s actually been computational fluid dynamics research that has shown that as blades get stockier, essentially, you get a better grip on the water and you get more efficient at rowing,” he says.

Concept2, a producer of rowing oars, has become one of the most dominant brands and designers in the space in the U.S. Three of its most notable blade designs include the “Big Blade,” the “Smoothie2” and its latest design, the “Fat2.”

But rowing isn’t a perfect science, and there are numerous variables athletes have to contend with when they are in the water, no matter how good the design of the oar is, Neils says.

“The analogy I like to give for rowing is that almost nobody ever takes a perfect stroke,” he says. “It’s almost like a golf swing, where, yes, you can connect on a ball and get an awesome swing.

“But you aren’t going to get a birdie every time you are out there. In a typical 2-kilometer rowing, which is the Olympics distance, I think you’re taking about 250 strokes,” he adds. “It’s very rare that all those would be good for all eight people who are on the boat. Any minute changes to the angle that you carry the blade or anything like that have severe consequences to the boat.”

The third key change is the use of sensors and the collection of data, a trend that rowing has only really gotten into in the past decade or so with the introduction of devices like NK Sports’ SpeedCoach GPS and Empower Oarlock, which allow for the easy capture of a boat’s speed, a rower’s stroke rate, distance traveled, overall time and more.

“[These devices] now tell everybody’s pitch angle, the angle of the oars, the depths they go in, the length of the oar as it goes through the water, the angle it comes out, the time it comes out. They can tell when somebody is off by just a little bit.”

Sensors are also being added to footplates to see how much pressure rowers are using when they are pushing off.

“I think that the most recent technological revolution — that it’s data driven,” he adds.

They haven’t gotten it all figured out yet, though, Neils explains.

Rowing equipment makers are still trying to wrap their heads around how to capture data on “boat feel.” Every rower is different, and data can only get you so far — at least for now.

“Now that there are sensors on everything, I don’t think anybody rows the same for us to figure out the perfect stroke,” he says. “More importantly, when you get in a boat with someone else, you have to be in sync, and I don’t know if data has been able to capture that yet. Maybe with AI, there’s something there.”

Cesareo Contreras is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at c.contreras@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter @cesareo_r and Threads @cesareor.