Published on

This music technology class takes students back through history — way, way back

In MUSC 2320: 40,000 Years of Music Technology, James Gutierrez traces innovations from Paleolithic-era bone flutes to theremins and AI. He encourages students to try them all.

Even in Northeastern University’s music department, where percussion rehearsals and string tune-ups emanate through the halls, you’d be hard pressed to find more sonic chaos than in Ryder 364 on a Monday afternoon.

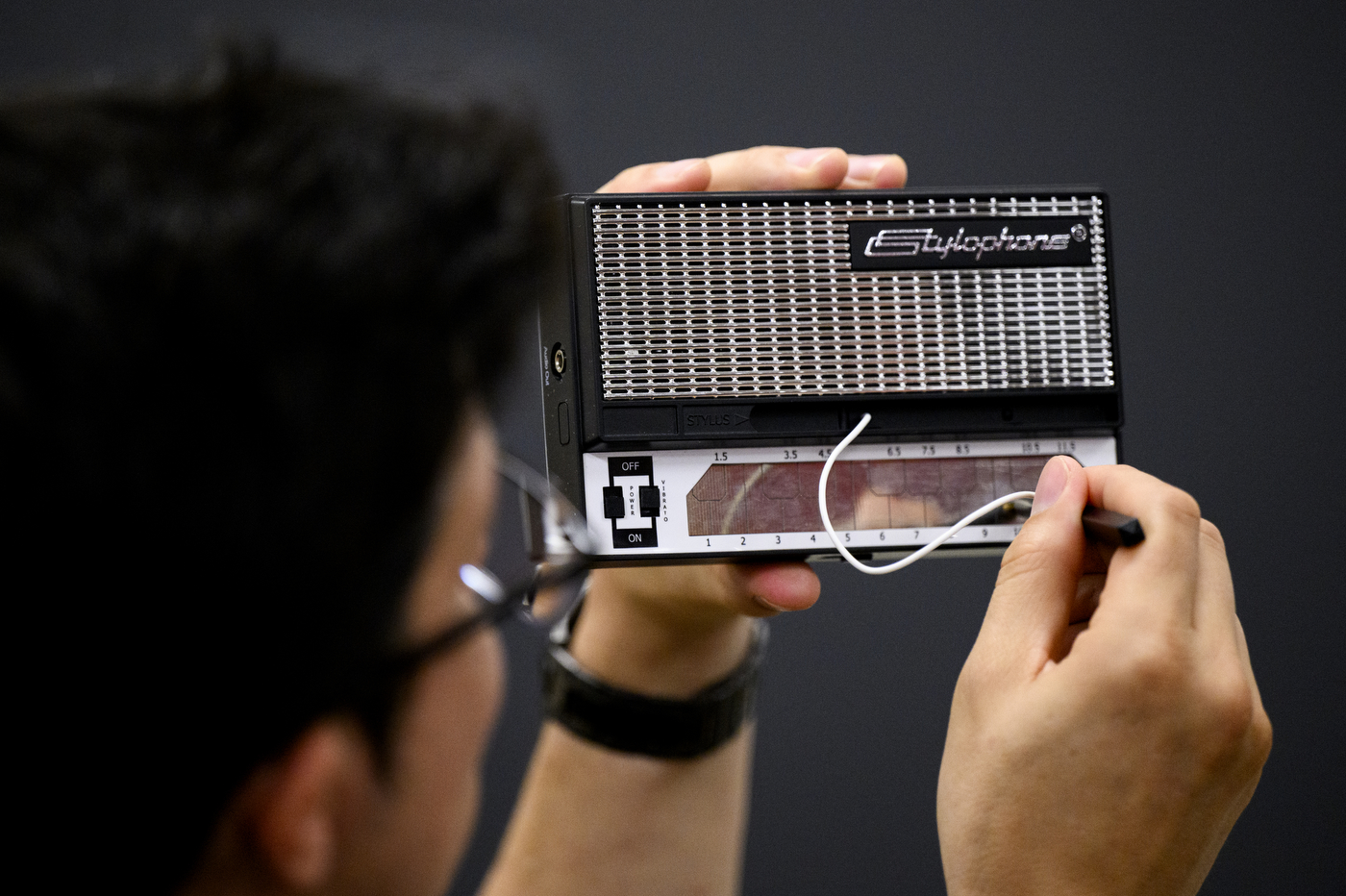

Inside the mid-sized rehearsal space, students in assistant teaching professor James Gutierrez’s class are taking turns trying out instruments. “Eclectic” doesn’t even begin to describe the assortment. On one table, a pocket-sized electronic synthesizer called a Stylophone sits next to a violin and two wine glasses half-filled with water; on another, there are 3D-printed replicas of bone flutes traced to ancient civilizations in Europe.

Daschel Knuff, a first-year music industry major, laughs as he struggles to sustain a vibration from a singing bowl, used throughout the world to encourage peaceful feelings during yoga, meditation and spiritual ceremonies.

“Did you have a corrupting thought?” Gutierrez jokes.

Perched like a challenge at the center of the room is a theremin, an electronic instrument that makes sound without being touched. If you’ve seen a 1950s sci-fi B-movie, you’ve heard its eerie, high-pitched wobble. Players manipulate the pitch by moving their hands near and away from a metal antenna, bending the soundwaves.

It’s as tricky as it sounds. After Gutierrez gives a capable demonstration, the students have varying levels of success wrangling coherent tones out of the temperamental device. (The world’s most famous theremin player, Clara Rockmore, once said she couldn’t “register any internal emotion at all” without affecting its pitch.)

This is the “hands-on” portion of MUSC 2320: 40,000 Years of Music Technology, a music department fixture since 2017. In the lecture beforehand, Gutierrez covered instrumental fads of old including a glass armonica (a Benjamin Franklin invention inspired by the sound a wet finger makes circling the rim of a glass), as well as the impact of electricity on music — hence the synthesizers.

The class takes its name from carbon dating of Paleolithic-era flutes discovered in the caves of Northern France — the earliest known instruments. From there, Gutierrez charts a comprehensive history through the lens of key innovations, from ancient Greece and the early American colonies to the advent of electricity and AI, which represents the same thorny inflection point for music as it does for many other fields.

“It was a seminal course in my education,” says Gregory Gold, a 2023 music graduate and aspiring composer. “It expanded my perspective on the creative process and the value of experimentation.”

Gutierrez thinks the class framing gives students a more comprehensive understanding of the role music plays in society than the traditional music history curricula in many university programs.

“It’s more useful than ‘composers who existed between 1200 and 1900’ as the primary focus, especially for those in our music technology and industry programs,” Gutierrez says. “Even DJs today creating music with AI, they share goals with human beings making music 100 years ago, 500 years ago, 5,000 years ago.”

Dierdre Loughridge, a music professor and associate dean who designed the course and taught it until 2021, says it’s useful for students pursuing careers in music to recognize how structures we take for granted — like a piano’s 12-note scale — grew out of technological developments, as well as how such innovations have been adopted and discussed throughout the centuries.

“There is a lot of polarized and uncritical thinking around technology,” she says. “Either the newest is always the best, or the new tech is destroying what we hold dear. Really, every tool has affordances and constraints. Rather than ‘tech good’ or ‘tech bad,’ we have to think through these trade-offs to make good decisions about them.”

Bone flute to autotune to…

As the class syllabus makes clear, worries over how new tech will impact music are timeless. When Loughridge conceived of the class affectionately nicknamed “40K Music” in the early 2010s, there was a lot of handwringing over autotune, the sound processor that adjusts pitch in vocals and instrumentals.

“I initially called it ‘Music & Technology: From Bone Flute to Autotune,’” she says. But by the time she brought the class to Northeastern, autotune was neither controversial nor new. “As ‘40,000 Years of Music Technology,’ it’s an open-ended class that brings a long historical perspective to today’s technological changes.”

Even DJs today creating music with AI, they share goals with human beings making music 100 years ago, 500 years ago, 5,000 years ago.

James Gutierrez, assistant teaching professor of music.

As such, the course material expands periodically on the back end. This semester, Gutierrez delves a bit into neural prosthetics, which some speculate could allow users in some not-too-distant future to control multiple instruments with their minds. One week, he had students create a song using Suno AI, imputing lyrics, genre and artists whose styles they wanted to imitate to generate a new composition.

“These are going to be the leaders in music tech tomorrow, and they will have to make decisions about what an ethical use of AI is in their field,” he says. “It’s important that they develop a sense of what it offers as a tool.”

Chronologically, there’s a lot to cover before that. Too much, in fact — the syllabus is heavy on the bookends. “I spend the first half within 40,000 to 5,000 years ago, and the second half is mostly from 1800 on,” Gutierrez says. “There’s a lot in the middle that’s important, but I’m trying to draw the longest thread from the most ancient and stable patterns to the present day.”

The lectures outline the ways technology has altered the destinies of some of today’s most ubiquitous instruments. In Renaissance Europe, for instance, the violin — today’s leader of the orchestra — was a lower-class folk instrument. High society players preferred its larger counterpart, the viol. That changed in 1600s-era Italy, when musical performances became important displays of wealth for prominent families.

“The instruments that were louder and able to project in a large concert hall were more often selected,” Gutierrez says. Thanks to a few timely tweaks, the violin fit the bill. “Overnight, we have an acceptance of the violin as the new higher-class instrument, replacing the viol.”

It’s electric

In many cases, those tech-impacted trajectories are wholly unpredictable. During a June lecture, Gutierrez zeroed in on the electric guitar. The first guitars equipped with electric amplification systems came out in the 1930s and were marketed as classical instruments — traditional Spanish-style guitars are too soft to be heard above a full orchestra. Blues and rock and roll changed that; the instrument’s status as a signifier of virile masculinity had fully taken hold by the mid-1950s, persisting for decades.

But the guitar’s story is far from over, Gutierrez points out. In recent years, there has been a surge of women taking up the instrument — after decades in the vast minority, girls are signing up for guitar lessons at exponentially higher rates than boys, according to guitar studios. The reason? Taylor Swift.

“It’s interesting to see how certain tech was used in ways it wasn’t necessarily created for,” says Zoe Mumford, who took 40K Music last fall and cites the guitar lecture as one of her favorites. A third-year music tech major with a minor in ethnomusicology, Mumford is currently on co-op at Eighth Day Sound Systems, which coordinates sound systems for major musical tours for stars including Olivia Rodrigo, Blink-182 and Swift.

For students like Mumford, who is training to become a professional roadie, the class offers valuable industry perspective before they enter the workforce, along with technical knowledge and hands-on practice with cutting-edge tools.

It also allows them to further explore topics of interest, and “go down some really interesting rabbit holes,” Mumford says. For her final project, she researched “music made with rocks,” a surprisingly fertile subject with case studies ranging from ancient cave dwellers to the experimental Icelandic band Sigur Rós.

“Understanding the origins of certain industry standards has been really helpful,” Mumford says. “Some technologies go back further in time than I would have thought.”

For Gutierrez, teaching 40K Music is a valuable opportunity to impart the idea that music, at its core, isn’t fundamentally made up of its structures and tools, but rather a process borne of humans’ universal need to seek it out. A self-taught jazz pianist, he didn’t learn to read music until college. So he’s supremely aware that things like notation are byproducts of music — not music itself.

“The earliest example we have is from around 1200 BC, which means there are at least 35,000 years of music making before notation,” he says. “It’s a useful tool, but it’s not the first thing you should learn or think of about human music making.”

His academic research focuses on music and embodied cognition, or the way that people integrate tools into how they think and use their bodies. Loughridge says that insight, combined with a keen interest in learning about new instruments (and expanding the music department’s collection of them), make Gutierrez a perfect fit for 40K Music.

“I’ve always considered music to be an integrated phenomenon, rather than just a discrete ‘follow these prompts and you will do music’ process,” Gutierrez says. “So this class is obviously my favorite that I’ve taught.”

Schuyler Velasco is a Northeastern Global News Magazine senior writer. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X/Twitter @Schuyler_V.