Published on

Pompey was elected a Colonial-era ‘king.’ Did researchers find the foundation of his home outside Boston?

“It gives us renewed appreciation for King Pompey and the celebration electing Black kings and governors in New England,” says Kabria Baumgartner, a dean’s associate professor of history and Africana studies at Northeastern.

SAUGUS, Mass. — At first glance, it may not look like much more than a hole.

But the 4-foot deep excavation of a rock foundation behind a chain-link-fenced backyard transports Northeastern University historian Kabria Baumgartner back 275 years — to a unique colonial New England tradition in which a formerly enslaved Black man named Pompey was elected “king.”

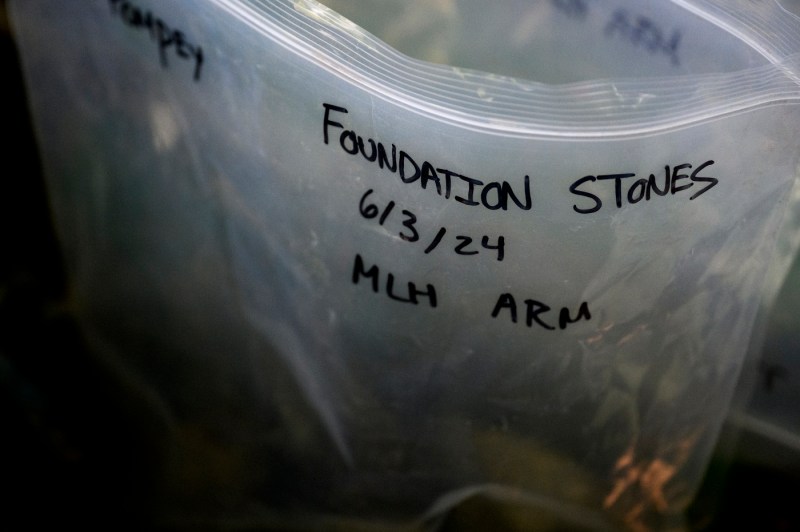

On the shores of the Saugus River about 10 miles north of Boston, she is surrounded by small, smooth stones — unearthed by a team of archeologists — believed to be the remains of Pompey’s former home.

“It really comes to life,” says Baumgartner, a dean’s associate professor of history and Africana studies at Northeastern. “I spend a lot of time in archives looking at written materials. It feels different to come to a site.”

Between about 1750 and 1850, New England had at least 31 elected Black kings and governors, most of whom were enslaved, according to the New England Historical Society. Black kings were elected in colonies such as Massachusetts and New Hampshire where the white governor was appointed; Black governors were elected in colonies where the white governor was elected.

The elections on “Negro’s Hallowday,” as colonist Benjamin Lynde Jr. called it, or “Negro Election Day” were the most important day of the year for Black people, and were held on the same day white men in New England gathered to vote for their leaders, according to NEHS.

“It was kind of a very lively, joyful celebration,” Baumgartner says, noting accounts of Black Election Days in other colonies. “We know that there was talking, dancing, and singing and drumming, which relates to west African tradition.”

But Baumgartner sees the celebrations as more than mimicking elections held by white colonials.

“It was absolutely an assertion of civic rights,” Baumgartner continues. “That (the Black community) too had a voice, that they too had opinions about the government and how it was run. And this was their opportunity to voice it.”

The celebrations continue today at an annual event in Salem, and Negro Election Day is commemorated in Massachusetts on the third Saturday in July.

Pompey was one such elected king, living in what was then part of the city of Lynn. He is portrayed in historical accounts as an esteemed leader who hosted free and enslaved Blacks from the region on Black Election Days at his property along the Saugus River.

But Baumgartner says that most of the information about Pompey is from historians who lived several decades after Pompey died, particularly the early 19th-century Lynn historian Alonzo Lewis. Those accounts are difficult to confirm since such historians didn’t use footnotes and often compiled oral histories that lacked documentation, Baumgartner says.

“We think Pompey was born in West Africa and, at some point, was trafficked across the Atlantic Ocean, a horrific journey often referred to as the Middle Passage,” Baumgartner says.

Baumgartner also says Pompey claimed royal African ancestry, which a few enslaved people did at the time.

Featured Posts

So, historians have to do some digging — both figuratively and literally — to confirm these accounts.

That’s where Meghan Howey, Alyssa Moreau and Diane Fiske of the University of New Hampshire’s Great Bay Archaeological Survey join in.

Fiske conducted a “forensic deed analysis,” as Howey called it — tracing public documents through the Essex County Registry of Deeds and genealogical records.

The deed analysis, coupled with Baumgartner’s research using maps, probate records and historical newspapers, gives us a more complete picture of Pompey.

For instance, research confirmed Pompey’s 1745 marriage to a woman named Phyllis or Phebe,and that he was enslaved by a man named Daniel Mansfield II.

Historians believe Pompey was manumitted, or freed, by the 1750s, but apparently not — as legend holds — in Mansfield’s 1757 will.

“It’s not in the will, and we haven’t found any manumission papers,” Baumgartner says. But she notes that manumission papers are rare to find.

Upon securing his freedom, Pompey borrowed money from another Black man named Isaac Hower to purchase two acres along the Saugus River in 1762. The deed was not recorded until 1787, however, at which time Pompey signed the property over to Hower’s widow, Flora.

But many questions remain unanswered. For instance, if not freed in Mansfield’s will, did Pompey free himself?

Fiske noted that the Mansfield family were clothiers. Might Pompey have used side work to save up money to purchase his freedom or continued that trade upon manumission?

But perhaps the biggest question is where exactly Pompey lived and hosted these Black Election Days.

Last week, it’s likely to have been answered.

“I have extreme confidence this is a 1700s foundation and the connection to King Pompey is very compelling,” Howey said, standing on the edge of the backyard hole on the banks of the Saugus River. “This is very promising.”

Howey explained that the foundation demonstrates several eras of local building techniques.

At the top, there is concrete laid over cut stones, which Howey suggested was probably a 20th-century attempt to shore up the falling wall.

Below that layer, cut stones are loosely held together with mortar, which suggests a date around the late 19th century, Howey says.

But below that layer are smaller, smooth stones from the nearby tidal river.

“It’s a pretty labor intensive way to build a foundation,” Howey says.

“But if you don’t have many resources, this is how you’d do it,” Baumgartner adds.

Moreover, the deed references an oak tree and a colonial-era road bordered by a stone wall — all of which are just steps away.

As for the hole, Howey says that she would like to clean and map the full foundation of the home, and also expand the dig to see whether they can find artifacts related to the Black Election Day activities — for example “middens” or heaps of trash from feasting.

“People edit what they write down, not what they throw away,” Howey says, noting that the team has found some late 18th-century pottery around the site. “It’s the verification — we like to say ‘trash doesn’t lie.’”

But standing by the hole and looking across a bend in the meandering Saugus River to a field and wooded hillside, one can imagine dozens upon dozens of free and enslaved Black people gathering, enjoying a feast and celebrating.

“Historians described this site just as it feels now and, although they were often accused of being overly romantic, it is a peaceful, calm and picturesque site,” Baumgartner says. “It gives a new appreciation for King Pompey and the celebration electing Black kings and governors in New England.”

Cyrus Moulton is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at c.moulton@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter @MoultonCyrus.