Published on

Can pottery be therapy? This psychology student thinks so.

Fifth-year Northeastern University undergrad David Chatson feels most at home ‘throwing’ in a ceramics studio — and he’s passionate about studying and sharing the peace he finds at the wheel.

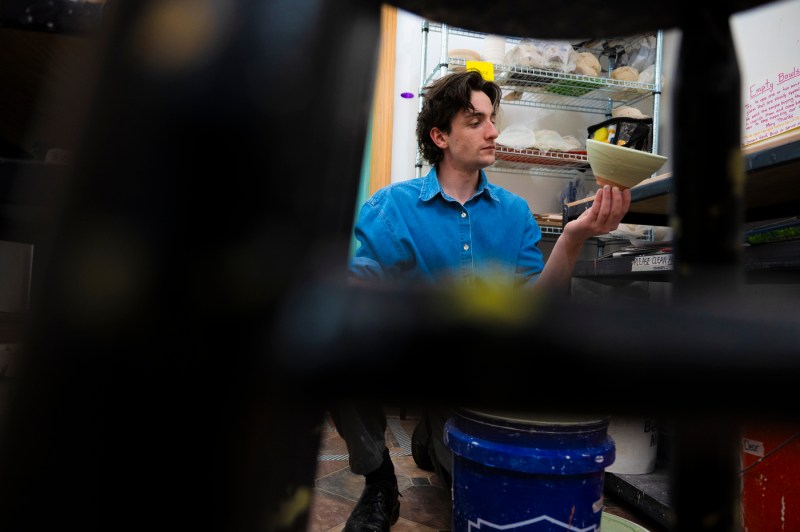

The Create ceramics studio in Boston’s Roslindale neighborhood is a tapestry of gentle, sturdy neutrals. Earthenware pots, bowls and teacups awaiting paint jobs rest on light gray shelves; white drop cloths and stone potter’s wheels take up most of the wood floor, all of it bathed in low afternoon sunlight gushing through storefront windows. But at the center of the space, David Chatson is focused on something small, slimy and black.

The previous weekend, the Northeastern University psychology major and a few friends took a drive to Wells Beach in Maine. There, mucking around the rocky tide pools, they were delighted to discover a natural clay deposit, which they scooped up and brought back to Boston. Now Alyssa Franczak, a computer science and game design major, plops the lump on a wheel, struggling to coax it into a shape while the small group of Northeastern students assembled for their weekly pottery session looks on.

“It’s too soft,” Franczak sighs as the walls of the cylinder she’s formed buckle. Even so, she’s clearly enjoying getting her hands dirty. “I sit in front of a screen all day for my major, so this is a nice break,” she says.

After a while, Franczak shakily works the mound into a small bowl, but she and Chatson eventually decide it needs to dry out for another week. This type of experimentation — and failure — is one of the many delights Chatson, 22, finds in making pottery, which he’s been doing in earnest since his early teens. “I find it extremely cathartic,” he says in an interview. “It’s the one thing that’s always kept me grounded — taking that time to only focus on what’s directly in front of you. We don’t always get an opportunity to do that.”

But the meditative aspects of “throwing,” in pottery parlance, are more than welcome side effects of a beloved hobby for Chatson. They’re a calling. Though still finishing his undergraduate psychology coursework, he’s focused on a career centered around studying — and sharing — the benefits he and others have found at the wheel.

From a therapeutic standpoint, the mechanics of pottery alone are powerful, according to experts. “The centering in wheel work really helps people focus in, especially people who are traumatized, extremely depressed or anxious,” says Julia Byers, a leading art therapy scholar and a recent distinguished fellow at Northeastern University’s Global Resilience Institute.

Chatson has long been interested in a career as a therapist or social worker — and potentially incorporating art therapy into that work. But at Northeastern, “the button clicked” that pottery could serve as a focal point — both in terms of serving patients and contributing new, rigorous insights to the academic study of expressive therapies.

William Sharp, a teaching professor in Northeastern’s psychology department and a practicing clinical therapist, thinks Chatson’s combination of artistic skill, academic interest and enthusiasm could lend something unique to the therapy world.

“He’s really interested in figuring this out,” says Sharp, who has been a mentor to Chatson as he navigates a nascent research path. “I’ve been so impressed with how much energy he wants to put into it.”

Doing the work

Chatson took his first pottery class in ninth grade while at boarding school in Connecticut. He excelled in art class, but everything else proved difficult; he dropped out in the middle of his junior year.

“I never really found my footing, for one reason or another,” he says. But he had no plans to give up on education — after finishing his GED, Chatson moved to California and enrolled in community college, where he fared much better. He was accepted to Northeastern as a sophomore in 2020.

On campus, he settled on studying psychology, taking classes in cognition and personality theory. “There are always a handful of students who stand out, and he certainly was one,” says Sharp, who had Chatson in a large lecture this past fall. “He always came up after class to ask questions.”

It’s the one thing that’s always kept me grounded — taking that time to only focus on what’s directly in front of you. We don’t always get an opportunity to do that.

David Chatson, Northeastern University psychology major

Along the way, he volunteered and held summer jobs teaching arts to kids. Pottery remained a fixture — Chatson has a wheel in his Roxbury apartment and has served as an instructor for the Clay Cave, Northeastern’s pottery collective. Open to all students and faculty, the club attracts first-timers and experienced throwers alike.

“The first thing I teach to anyone who’s just learning pottery is to throw a cylinder — walls going straight up and down,” Chatson says. “Every other form derives from that. If you can throw a cylinder, you’re already halfway to a vase or a bowl.”

But the idea of combining his classroom and extracurricular interests really crystallized on his first co-op. “It was at a pottery studio in Maynard — I taught kids’ classes, held events, all sorts of things. It was a lot of fun. And some families would sign their kids up for private lessons with me.”

In those weekly one-on-ones, Chatson was amazed how quickly he built rapport with his students, who would talk frankly with him about their lives, worries and hopes. After a few months of such sessions, pottery’s potential in a therapeutic setting seemed like a no-brainer. “There are a lot of different aspects you can explore,” he says. “I think the sensory motor experience and the auditory stimuli of throwing on the wheel can relieve stress and anxiety. But what interests me the most is that there are a lot of people out there who are averse to therapy in some way.”

Building up, letting go

Centering sessions around an activity can lower those mental barriers — an approach that’s common to the wider art therapy world and widely researched in empirical terms. Studies have shown that clay therapy can reduce biological indicators of anxiety and depression in teenagers and adults; a 2023 randomized trial of high-school-aged girls in Hong Kong found that subjects who created clay works with their hands had reduced levels of the stress hormone cortisol in their hair.

Byers adds that pottery-making in particular has a high failure rate — a useful tool in priming patients to move through painful past experiences, from grief and trauma to failed relationships. “Maybe 1 in 5, 1 in 10 pots actually turn out, and it’s quite a lengthy process,” she says. “There are a lot of phases where things can go wrong, and if you have your heart set on that one piece and it breaks, you’re going to be frustrated and disappointed. The process itself helps people to come to terms with letting go.”

Sharp, at Northeastern, says that clinicians can get a lot of functional information watching a patient create art of any kind in a standard talk-therapy setting. “There are some basic biological things people might overlook,” he says. “Is there a difference in the left and right side of the brain — does [the patient] only really develop on the right side? How do they cross the midline? It’s a good way to rule out anything organic, like a brain tumor, and from there make assessments and move toward interventions.”

Featured Posts

Works of art, he says, can also serve as valuable reference points for patient progress. His favorite example is a pair of paintings by the artist William Krulek, on display in London’s Museum of the Mind. The first, “The Maze,” is an intricate, abstract cross section of the experiences and traumas at work in the artist’s brain. The second, “Out of the Maze,” shows a peaceful family picnic in a field — with “The Maze’s” skull tucked in a corner.“It’s really hard to get rid of stuff that’s in your head, but you don’t have to give it prime real estate in your mental life,” Sharp says. “When I use art in sessions, it helps people get certain blocks or helps put words to things they can’t normally.”

A trained artist like Chatson could bring an added dimension to the traditional therapy experience, Sharp thinks, because he can do the art alongside the patient. “I don’t think we have enough therapists interested in the insight and depth [gained from] that kind of work, and also who are tolerant of the fact that art can be messy.”

Full circle

For the moment, Chatson is interested in more empirical analysis of his beloved pastime. Sharp has helped him apply for a few small research grants, which, if he gets, he would put toward rented studio space and buying a wheel for regular group pottery therapy sessions. He’s open to the different forms that might take — partnering with an arts therapy collective in the Boston area, or pairing with a licensed therapist to conduct pilot studies looking at pottery-making through a quantitative lens. He’d like to collect data on how it might impact adolescents with depression, in particular.

“The best way for me to go about that might be to administer Beck’s depression scale, or the Hamilton Anxiety Scale to participants in Boston before and after the study, to see if there was a significant change or not,” he says. “In order for it to have validity I would need a licensed social worker present.”

All of his other plans — short and long term — revolve around pottery, therapy or both. This summer brings a full circle moment: he’s teaching psychology and ceramics at his old Connecticut boarding school, the Loomis Chaffee School. In the fall, Northeastern’s Human Services department is offering the university’s first-ever course on expressive therapy; Chatson plans to take it as one of his last psychology electives before graduating in the fall. After that, he would like to earn a master’s-based thesis. The future, he admits, is full of equal parts possibility and questions.

An immediate one: What will happen to that natural clay deposit? After letting it dry out another week, the students fashioned it into a small teacup; the Create studio won’t put it through their kiln, so the group will have to drive out to Braintree to finish it. “We’ll see if it ends up surviving,” Chatson says.

Schuyler Velasco is the campus & community editor for Northeastern Global News. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X/Twitter @Schuyler_V.