Published on

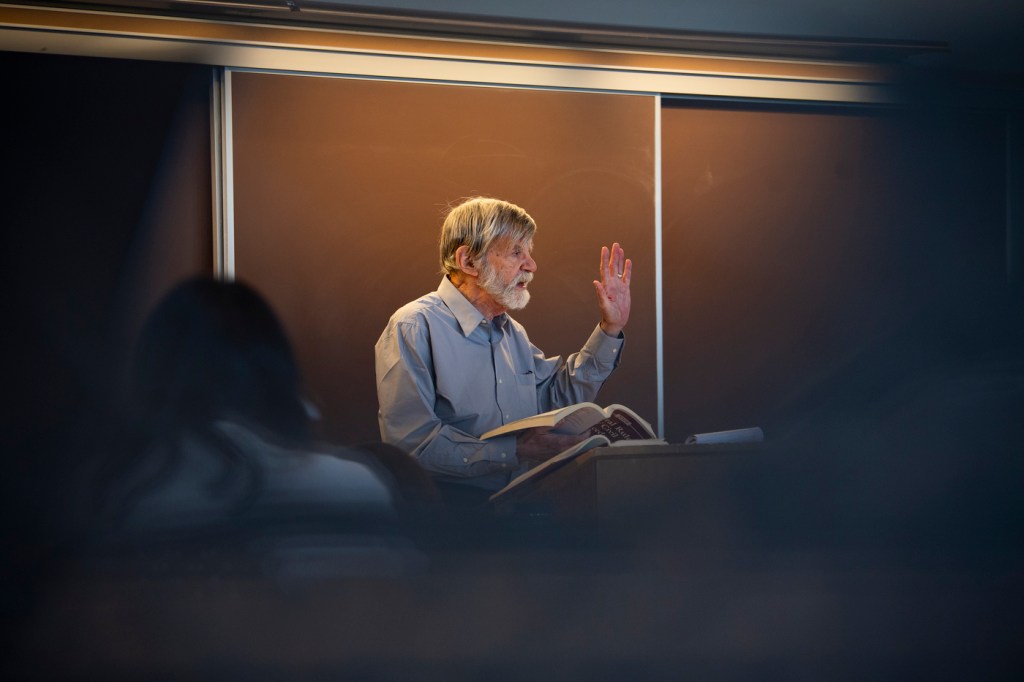

At 80, the legendary professor who beat Big Tobacco takes on sports betting

Northeastern law professor Richard Daynard argues that sports betting is an addictive public health risk — while applying lessons from his successful decades-long fight against cigarettes.

Commercial sports gambling is generating more than $11 billion annually from people in the U.S. The betting action is driven by widespread ad campaigns backed by a powerful conglomerate of state governments, sports leagues and celebrity endorsers.

Standing in opposition to the new wave of legalized sports betting is Richard Daynard.

The legendary Northeastern University law professor alleges that consumers are lured online to betting sites by a proliferation of misleading ads, resulting too often in life-ruining addictions that are creating a public health crisis.

Daynard compares the threat of sports betting to the era of Big Tobacco, which for decades was not held responsible for the harm inflicted on its users. “There has been essentially no organized opposition to the gambling interests,” Daynard says.

On a 60 Minutes report on Sunday that focused on the surge of gambling addicts — mainly young men who are vulnerable to the industry’s proliferation of alluring ads — Daynard said he was reminded of the highly profitable strategy deployed by American cigarette companies over the past century.

“We’re dealing with an addictive product: We’re dealing with an industry that will still defend sometimes on the basis that ‘it’s really the smoker who’s making the choice,’” Daynard told 60 Minutes. “So we have that exactly with the gambling industry.”

The dynamic of luring people who are vulnerable to an addictive product reminds Daynard of the strategy deployed by American cigarette companies over the past century. Daynard helped lead the legal fight against Big Tobacco, an exhaustive struggle that languished for decades — until breakthrough court judgments of the 1990s led to large penalties against the industry and bans on secondhand smoke in virtually all public places.

Northeastern’s Public Health Advocacy Institute (PHAI), a Daynard-led organization that evolved from his opposition to tobacco, filed a lawsuit in December against the online betting site DraftKings alleging that it offered a deceptive bonus to new customers on behalf of a “known addictive product.” In order to receive an advertised $1,000 sign-up bonus, users would have to bet an average of $276 daily over three months, according to Daynard’s class-action filing.

Legal experts have suggested that Daynard’s credibility and the strength of his allegations may inspire similar lawsuits against other companies across the relatively new sports-betting industry, which was triggered by a 2018 Supreme Court ruling that so far has enabled 38 states and the District of Columbia to legalize — and draw tax revenues from — sports betting.

Daynard and his former Northeastern law student Mark Gottlieb, the executive director at PHAI, have allied with Harry Levant, a gambling addiction counselor who is pursuing a doctorate at Northeastern. Levant understands the vulnerabilities of bettors: As a lawyer in Philadelphia he stole more than $2 million from people who trusted him before turning himself in, seeking help and vowing to counsel and support others who are addicted.

The tobacco industry rejected responsibility for the health issues suffered by smokers. Under legal pressure that Daynard helped direct, the companies eventually were held accountable for the addictive and harmful nature of their products.

“Dick brought a focus on the actions of the tobacco companies and the recognition [that they were selling] an addictive product,” Levant says. “That is something I had been talking about for a number of years about the gambling industry — that it’s about how they deliver a known addictive product in both a deceptive and inherently dangerous way.”

Levant and Gottlieb were also interviewed by 60 Minutes, with Gottlieb calling for federal sports-betting regulations similar to those that have reined in the tobacco companies.

“Right now it’s sometimes described as the ‘Wild West’ because there’s almost no controls at all,” Gottlieb told 60 Minutes. “What’s it going to look like five years from now? I think these products have the potential to become significantly more addictive and dangerous in a very short period of time.”

The Northeastern trio of Daynard, Gottlieb and Levant have been working with U.S. Rep. Paul Tonko, D-New York, to develop federal legislation that defines gambling as an issue of public health — on the same level as tobacco, alcohol, opioids and other addictive products

“It’s a very similar paradigm,” Levant says of the fight to regulate sports betting. “As Dick likes to say, ‘We’ve been down this road before with tobacco.’ The gambling companies are doing the same thing, and Dick Daynard has decided to bring his full expertise to the issues around gambling with a very similar perspective.”

Why is Daynard doing so at an age when he could be celebrating his achievements?

Why, at 80, is the renowned activist taking on this latest fight?

‘Are you making a big, big mistake?’

In 1988, when The New York Times profiled Daynard as a leading protagonist of the anti-tobacco fight, his legal strategy was yielding little promise: At that time Big Tobacco had not suffered a lost judgment in 321 liability cases filed over the past 35 years.

A 1964 report by the U.S. surgeon general had laid out a direct relationship between cigarettes and lung cancer. And yet smoking continued in public virtually everywhere — in offices and airplanes, in restaurants and doctor’s offices and hospitals.

“It didn’t look like it was going anywhere, the cases weren’t winning at that point,” Daynard says in an interview at PHAI headquarters on Northeastern’s Boston campus bordering The Fenway. “And I remember asking myself, ‘OK, am I psychotic?’ Which is probably not the worst thing I’ve ever been called. But I asked the question because if you’re the only one doing something and it’s not obviously working, are you making a big, big mistake?

“So I did ask myself the question,” Daynard says. “I decided, nope, I don’t think so. I don’t think I’m making a big mistake.”

As leader of the Tobacco Products Liability Project at Northeastern, Daynard offered a clearinghouse home for opponents of the industry. The project represented a widespread constituency of agendas and opinions galvanized by Daynard’s goal of winning liability verdicts and settlements for smokers and their families that would ultimately result in higher prices for cigarettes.

It was a practical, dispassionate strategy that would succeed where the emotional approaches had failed. The best way to prevent future generations from smoking, reasoned Daynard, would be to make cigarettes too expensive for kids.

Daynard’s role was to develop strategy while offering advice and support. But he was never the litigator.

“I knew the one thing I was never going to go into was litigation,” says Daynard, University Distinguished Professor of Law at Northeastern. “I had no interest whatsoever in doing that, even while I was in law school. For whatever reason I was not indoctrinated in trial lawyers as heroes.”

His iconoclasm was refined during his law studies at Harvard, where he also realized that he didn’t want to be a financial attorney either.

What he wanted was to become someone who made a difference.

“In any of my projects I’ve been involved in, including sports betting, the purpose of the project is to make a real change in the world,” Daynard says. “Being on the right side of an issue does not do it for me. I’d rather be on the right side than the wrong side, but in terms of actually doing things? I want to do things that will make the world a better place.”

He remembers having a career discussion around the age of 12 with his father, David Daynard, who ran a family business making clothes for Broadway performers. Daynard grew up delivering orders to a customer list that included Harry Belafonte.

His dad, an erudite tailor, encouraged him to follow his heart.

“I said to my father, ‘Maybe I’ll inherit this business.’ And he said, ‘God forbid,’” Daynard recalls. “He said, ‘I’m going to make enough money so you don’t have to worry about it. If you want to be a teacher or whatever you want to be, you can be that.’”

Armed with his Harvard law degree along with a master’s in sociology and a Ph.D. in urban planning from MIT, 25-year-old Daynard joined Northeastern’s law faculty in 1969. He taught consumer protection, an unusual subject at that time.

“He used to wear bell bottoms and a dashiki,” Carol Daynard says of her husband, who kept his hair relatively short with his signature beard. “He used to sit on his desk in the lotus position when he taught his classes.”

Daynard credits his empathy for social justice to his mother, Sarah Weidenbaum Daynard, a schoolteacher in New York.

“When I first met Richard, his father had just died,” says Carol Daynard, who worked as a school administrator until her retirement. “His mother, until her death, used to travel with us all the time. I wouldn’t say she was a feminist activist, but she certainly lived the feminist life. She set that kind of example and she encouraged him.”

The young Northeastern professor would routinely object to entering a room filled with secondhand smoke (a term not yet conceived). He joined forces with the anti-smokers simply because he believed in the movement, joining the Group Against Smoking Pollution (GASP) of Massachusetts and becoming its president in 1983. Big Tobacco looked down on its opponents as a disjointed crowd of outsiders and misfits that Daynard would eventually lead.

“Let me tell you, it was a collection of odd characters at these meetings,” Carol Daynard says.

The tobacco companies contended that smoking was a personal choice exercised freely by their customers. Daynard argued that many of those customers were addicted to cigarettes as a result of a Big Tobacco strategy to create those addictions.

Instead of lobbying legislators or making arguments in open court, he worked behind the scenes to provide plaintiffs with the evidence, arguments and courage to hold the tobacco companies responsible for an industry that to this day results in more than 480,000 deaths in the U.S. annually, according to the American Lung Association.

Results had already been trending Daynard’s way when a congressional appearance by tobacco leaders doomed them.

“Everybody saw all of the [Big Tobacco] CEOs raise their right hand, swear to tell the truth, and then say that no, nicotine is not addictive and no, they all agreed that we do not know whether cigarette smoking causes any human disease,” Gottlieb says. “They all said that and it became a bit of a national joke at that point. And that was really the beginning of the end of the conspiracy by 1999. It was over.”

‘Somehow I’ve loosened up’

Tobacco and addiction, litigation against sugary drinks, gun violence prevention — these are among PHAI’s targets. The evolving dynamic in each area creates a sense of faith among Daynard, Gottlieb and Levant that the need for sports-betting regulation will be recognized.

“He is and has almost always been frighteningly sharp and ahead of the curve in terms of realizing what was going to work strategically,” Gottlieb says of Daynard. “And that absolutely continues.”

A pack of cigarettes in 1984 cost $1.10 on average; today in Daynard’s adopted state of Massachusetts the average price is $11.11. Smoking has been banned everywhere.

For Daynard it’s an intensely personal satisfaction that he feels. He didn’t much care when advisers and critics told him his ambitions were hopeless decades ago, and so the plaudits haven’t changed how he thinks of himself or the way he lives. He continues to drive a beloved 17-year-old Toyota RAV4 that his two adult children wish he would replace. Proceeds from court awards and settlements have helped fund PHAI.

As he speaks of the criminality of Big Tobacco and the public health dangers of sports betting, he does not express the anger that may be expected of a lifelong activist. There is a practicality to his methods.

And yet, as his wife points out, he is driven by emotions and ambitions that he doesn’t fully understand.

“There’s the other side of him,” Carol Daynard says. “When we got married he cried at our wedding. And at first I thought, ‘Oh, he’s having second thoughts.’”

They were tears of happiness, says Daynard.

“So he does get emotional,” Carol Daynard says. “It isn’t there in the same way it is in these [other] activists; Richard is much more focused on the outcome than he is on the people along the way. And he’s not as concerned whether people like him or not.”

Richard Daynard’s father had been studying for a Ph.D. in English at Wisconsin when he was called to return home. His father had suffered a heart attack. David Daynard was entrusted with running the family business. He transformed it from a wholesale manufacturing operation into a retail business that connected him with the artistic community in New York.

There is a sense from Daynard that he is continuing to grow, to figure things out.

“This year was probably the first time in my life that I totally love teaching,” Daynard says. “I mean, I never liked or disliked it — but now I really love it. Somehow I’ve loosened up.”

The winter afternoon is giving way to dusk as Daynard reviews his life. He is not inclined to do so unless by request. The questioning runs in cycles, always returning to the subject of his father, the poet who became a tailor, providing the financial support that liberated his son to change the world. Daynard’s eyes widen, welling abruptly in the quiet. His trembling fingers reach for tissues.

“He wanted to be an English professor,” Daynard says. “He wasn’t able to do it. He wanted to make sure that I could grow up and do something that is meaningful to me.”

The triggering question is whether Daynard is proud of the work he has done and the difference he has made.

“At this very moment it makes me proud,” he says, pressing the tissue to his eyes. “But I am happy for my father, who I never thought of really in this context before. I never put together the fact that he wanted to be an English professor and hadn’t been — I never put that together with the fact that he wanted me to be something that was meaningful to me. I had no idea.”

Ian Thomsen is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at i.thomsen@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter @IanatNU.