Published on

Messy, resilient, ‘genius’: why this Northeastern food policy expert is thankful for SNAP

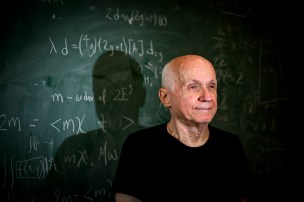

Chris Bosso’s new book traces the history of food stamps — from the Great Depression to modern culture wars about diet and inequality — and recommends ways to make the steadfast public assistance program even stronger.

A pivotal figure in the expansion of government food stamps, which give low-income citizens financial aid for buying food, wasn’t a community organizer, philanthropist or far-left politician. It was Richard Nixon.

In the early 1970s, the Republican president was facing an eventual reelection campaign against George McGovern, a Democrat from South Dakota and a champion of expanding federal aid. But unlike many of today’s post-Reagan conservatives, Nixon made a robust social agenda one of his hallmarks.

“Nixon was not going to be outflanked by anybody on domestic policy,” says Chris Bosso, a professor of public policy and political science at Northeastern University. “He had a remarkably liberal social agenda on the environment by today’s standards, on consumer safety, on food programs.”

With food stamps, Nixon nationalized the program and required states to participate, “essentially doubling it overnight,” Bosso says. Later that decade, another well-known Republican — Bob Dole from Kansas — would team up with McGovern on legislation eliminating a rule that required people to purchase food stamps before use, a bureaucratic hoop that made the benefits less accessible for the elderly and physically disabled.

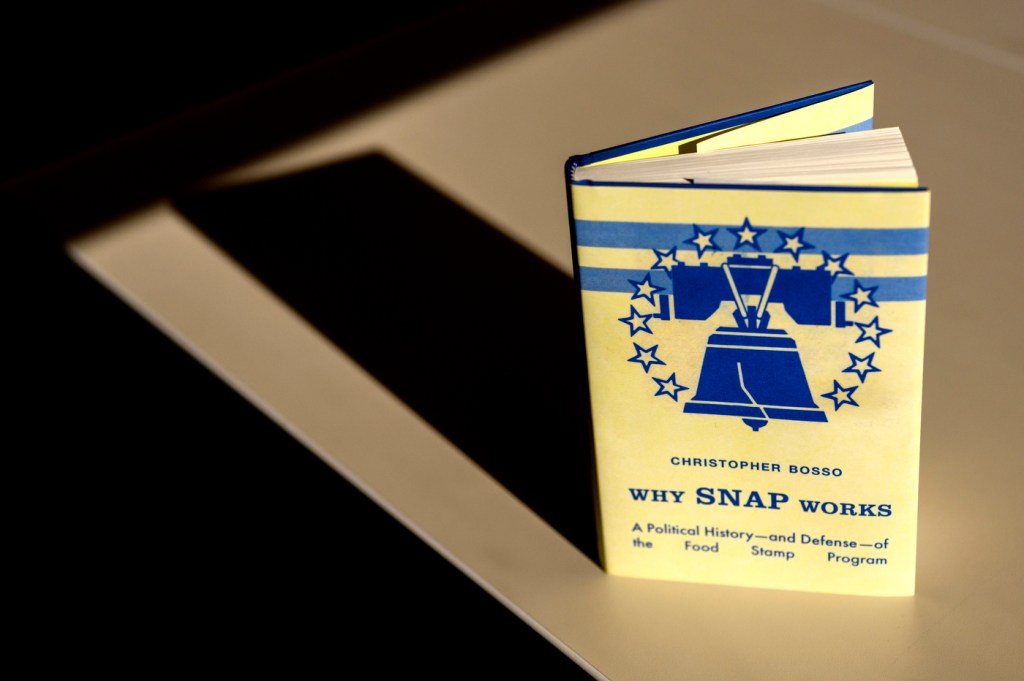

Nixon as food-security champion is one of many counterintuitive tidbits that Bosso chronicles in his book “Why SNAP Works: A Political History — and Defense— of the Food Stamp Program”, released by California University Press in October. Via a comprehensive account of the program’s near-century in various forms of existence, Bosso makes the case for SNAP as the most vital, sturdy social welfare program in the country, and offers up suggestions to make it even more effective.

“How did SNAP evolve [into] the nation’s foundational food-assistance program, not to mention an essential antipoverty program?” Bosso asks in the preface. “And why does SNAP survive, despite efforts in recent decades to pare back all forms of ‘welfare’? This book answers those questions by tracing SNAP’s long journey.”

In brief, the federal Food Stamp Program, rebranded as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in 2008, works as an income-based voucher system, giving qualifying U.S. resisdents monthly supplemental assistance to buy non-prepared food at businesses including supermarkets, convenience stores, and in more recent years, farmers’ markets. As of 2022, about 41.2 million people — about 12.5% of the U.S. population — and 21.6 million households are enrolled in SNAP, which accounts for close to two-thirds of the federal government’s spending on nutrition programs.

Bosso, whose expertise centers around food and agriculture in politics, and who has previously written books on pesticide regulations and the federal Farm Bill, says he was largely dismissive of SNAP before he took a deeper look.

“I went into it thinking that SNAP was lousy,” he admits. “I have always thought it was a halfway [measure], and we’d do better by providing low-income families with cash. The more I look at it, though, the more I appreciate its genius.”

That genius lies in the way food stamps combine broad political appeal with practical upside, the book argues. Rural, conservative politicians support it because it benefits their farming constituents; urban Democrats because it’s a vital lifeline for the working poor. Conglomerates like Walmart and Kraft support it because customers spend their food stamps with them.

It’s a voucher program, which Bosso points out has always been more palatable to American bootstrap sensibilities than cash welfare (Americans use vouchers for transit, Section 8 housing, and any number of other living essentials). Culturally, as the book lays out, people going hungry in a country that hypes itself as a land of plenty has historically proven a difficult thing for the public to stomach.

What’s more, SNAP helps people without compromising their dignity, Bosso says. Today, benefits are loaded onto an EBT card, indistinguishable from a regular Visa at checkout. “It enables a family in need to go to the store — Walmart, local bodega, whatever — And shop like any other family. And that is not a trivial thing.”

Buried pigs, burning corn

The program that would eventually become food stamps came about in a quintessentially American way: a public-relations fiasco. As the Great Depression ramped up in the early 1930s and destitute families sharply curbed their spending, farmers were faced with a glut of crops too cheap to sell for profit — from dry goods like wheat and corn to animal products like dairy and pork. As was routine, they destroyed the surpluses, killing and burying piglets, burning mountains of corn and pouring milk down the drain. At the same time, millions of Americans were going hungry.

“Imagine the visuals,” Bosso says. “It’s in all the newspapers, and films are running footage of destroyed food alongside people standing in breadlines. So there was this huge uproar. Eleanor Roosevelt was furious.”

The Department of Agriculture stepped in, giving out boxes of whatever food was in surplus in a given month to needy consumers. But often, that wasn’t an adequate way to feed people — some months the boxes would just have inedible grain, or, as in one infamous anecdote, nothing but grapefruit.

So under the direction of Milo Perkins, who ran the Federal Surplus Commodities Corporation, the Agriculture Department devised a system that allowed people to buy vouchers for free surplus goods in addition to their regular groceries. The program — particularly as an alternative to the shame of standing in a food line — proved wildly popular.

“It enabled people to go to the store and buy food with everybody else,” Bosso says. “And, if you had some cash, you might be in that same store to buy toilet paper. So it enabled retailers to actually expand their customer base a bit, because people who are otherwise standing in line for food will be in their stores buying food.”

After being discontinued in the post-World War II years, the Depression-era initiative was reworked via a series of pilot programs by the Kennedy administration. Lyndon Johnson signed the Food Stamp act into permanent law in 1964. Its chief champion in Congress was Leonor Sullivan, a representative from St. Louis and a story unto herself. “She’s the only woman in Congress who voted against the Equal Rights Amendment,” Bosso says.

It enables a family in need to go to the store — Walmart, local bodega, whatever — And shop like any other family. And that is not a trivial thing.

Chris Bosso, public policy professor at Northeastern University

SNAP in the modern era

In the 60 years since the Food Stamp Act, the program has endured, resisting funding cuts that have gutted other social welfare programs while playing a supporting role in heated cultural debates and major historical events along the way. During the COVID-19 pandemic, emergency increases in SNAP funding kept millions of Americans from falling into poverty, according to analysis from economists at the Urban Institute, a progressive think tank.

For decades, SNAP has prompted various arguments about who should be able to access benefits, and for which purposes. In 2018, for example, the Agriculture Department under the Trump administration proposed replacing a portion of SNAP recipients’ benefits with “America’s Harvest Box,” a monthly, pre-selected assortment of wholesale goods. Bosso writes that the idea was “denounced by nutritionists, hunger relief organizations, and, tellingly, food retailers as impractical, expensive, nutritionally deficient, and misguided. Critics equated the box with Great Depression-era bread lines in which the needy stood for handouts.”

Other legislative tussles have taken the form of SNAP-related work requirements (which will be tightened in 2024) and debates over what Americans should and should not be able to buy using SNAP. Over the years, lawmakers and advocacy groups have floated bans for items like sugary sodas and ultra-processed snack foods. “There’s an odd mix of nutritionists and conservatives who believe that people who are getting SNAP shouldn’t be spending it on bad food,” Bosso says.

He and other experts, however, counter that SNAP’s integration into the free market is a major strength. What’s more, in addition to furthering harmful assumptions that poor people can’t be trusted to make their own decisions, complicating the program’s rules chips away at the broad, messy coalition that has helped it survive. “As you start separating food into good/bad food the support behind the program begins to fracture. Kraft is like, whoa, I don’t produce broccoli,” Bosso says.

He still thinks there is room for improvement. Benefits can be hard to access, he says, and some states make it much harder than others.

“SNAP rules also could adjust to how most Americans actually shop and eat,” Bosso writes in “Why SNAP works.”

In most states, rules don’t allow benefits to be spent on prepared meals, despite their necessity for busy, dual-income families. “Most of us now buy more prepared hot foods — Costco’s famous $4.99 rotisserie chicken is not a ‘luxury’ food for budget and time-pressed families — and most of us spend less time to prepare and eat food at home,” he writes. “Yet SNAP’s rules … still assume that mom is in the kitchen, cooking from scratch.”

Yet on the whole, Bosso argues the program is something to celebrate. “If you took SNAP away, the entire social safety net would crumble under its own weight,” he says. “That we as a country provide this benefit that enables people to have a decent diet — the essential basis for decent life — that’s something to be thankful for.”

Schuyler Velasco is the campus & community editor for Northeastern Global News. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on X/Twitter @Schuyler_V.