Published on

Will airport security checkpoints become more efficient?

Northeastern researchers have been partnering with the Department of Homeland Security on projects to improve safety and efficiency at airports and other public settings.

The Sunday after Thanksgiving threatens to be the busiest travel day of the year — featuring long passenger lines at airport security checkpoints that yield anxiety and frustration.

Researchers at Northeastern are working on that.

Since 2008 they’ve been partnering with the Department of Homeland Security to pursue safety and efficiency in a variety of public settings. Recent work has included improvements to full-body scanners at airports as well as a complex system that connects passengers with their luggage at checkpoints.

Additional research is being done on behalf of so-called “soft targets” — stadiums and arenas, schools and houses of worship, even public sidewalks — where, eventually, a medley of sensors will be deployed to fend off weapons of mass destruction.

Northeastern’s role in finding and mitigating terrorist threats developed from an unlikely source. The alliance with Homeland Security can be traced back more than two decades to work undertaken by Michael Silevitch, a professor who was directing multiple research tracks that appeared to have little in common — including one to detect breast cancer tumors.

“If you think about how you diagnose a tumor, the simple way is with mammogram X-ray scans,” says Silevitch, the Robert D. Black Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Northeastern who serves as director of SENTRY, a Homeland Security Center of Excellence comprising more than 20 universities headed by Northeastern. “You take a set of 2D images using a CAT scan technique called tomosynthesis, which we helped develop, and you fuse that with other kinds of sensors to get a very accurate 3D representation of the structure in the breast.”

Similar methods were applied to discover smuggling tunnels as well as buried landmines and deposits of nuclear waste. That work was overseen by Northeastern’s Engineering Research Center based on a 10-year grant from the National Science Foundation — a breakthrough award (2000-2010) that “showed that Northeastern could compete with any research university in the country,” says Silevitch.

Northeastern was initially tasked by Homeland Security to focus on detecting explosives at airports 15 years ago. “People would ask me about the Engineering Research Center — ‘What does it do?’ — and I would say, ‘We find hidden things,’” says Silevitch, its director. “When Homeland Security put out a request for proposals for detecting threats in luggage — well, there’s no difference in terms of the strategies that you use to find a hidden tumor in the body or a hidden bomb in a suitcase. So that allowed us to win a very competitive 10-year Center of Excellence award called ALERT in an area where we had no prior experience.”

Solving the ‘left-behind’ problem

The advent of full-body scanners has made a positive impact on U.S. airport security since 2010, says Carey Rappaport, a College of Engineering Distinguished Professor.

“It’s night and day,” says Rappaport, who helps direct three government-funded security centers at Northeastern.

The vulnerability of traditional metal detectors is obvious: They’re unable to detect weapons made of plastic and other non-metals. The new scanners emit radiofrequency waves to locate suspicious objects of all kinds hidden within a passenger’s clothes.

Early versions of the machines infamously captured naked images of the body. That invasive technology has been replaced by machines that reveal no personal features. Instead, Transportation Security Administration (TSA) agents are provided access to generic body images featuring one or more small yellow boxes that mark the location of objects that require additional scrutiny.

An issue with the machines has been a large number of false positives triggered by slight movement, Rappaport says.

“It’s like kids moving around when you’re trying to take pictures,” Rappaport says. “All it takes is just a little hiccup. My own record going through an airport scanner is 17 yellow boxes, even though I didn’t have any anomalous objects with me.”

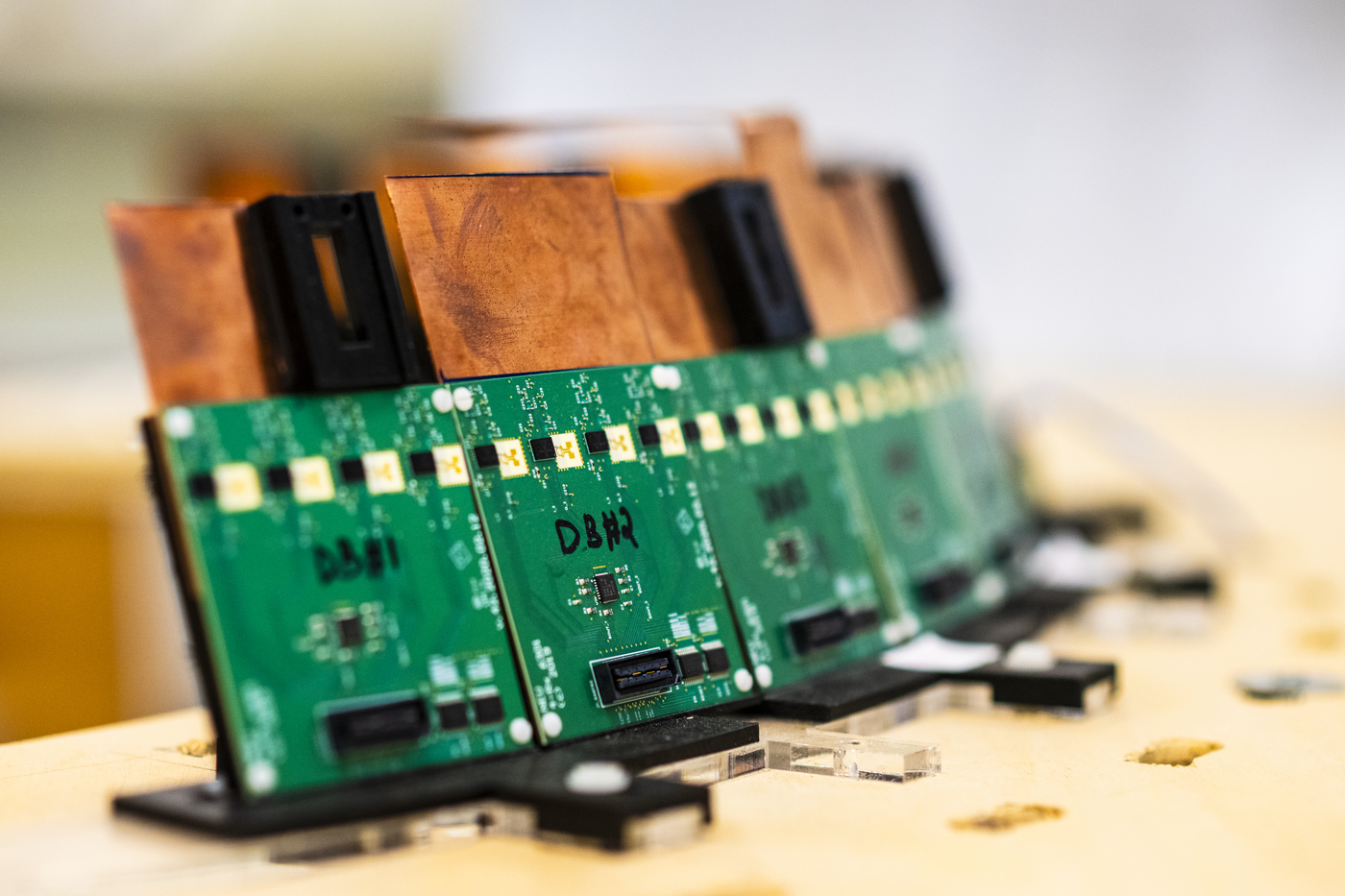

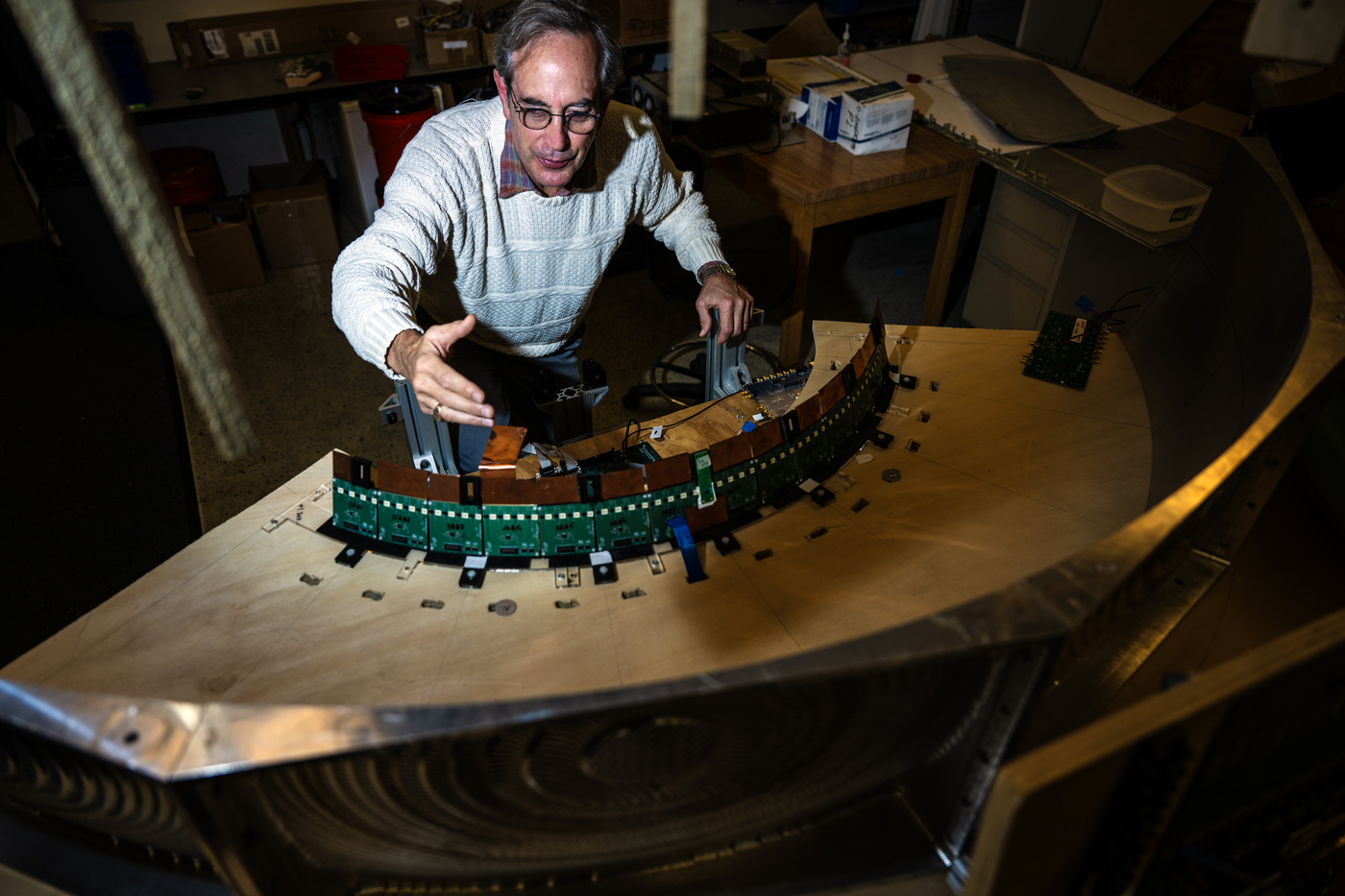

The high rate of false alarms helped inspire Rappaport to develop a next-generation version of the scanner. The machines currently take an array of images in a short time and marry them to create a single 3D picture. Rappaport proposed upgrading that monostatic technology with a multistatic version based on a small prototype that he built at his lab on the Boston campus. Rappaport’s scanner deploys more sensors snapping images at a much quicker rate — equivalent to inspecting the passenger from various points of view in a single moment.

“It’s going to give you more information,” says Rappaport, who believes the new technology would reduce scanning errors.

When Homeland Security put out a request for proposals for detecting threats in luggage — well, there’s no difference in terms of the strategies that you use to find a hidden tumor in the body or a hidden bomb in a suitcase.

Michael Silevitch, the Robert D. Black Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Northeastern who serves as director of SENTRY

Work on that prototype was paused by the COVID-19 pandemic. While it remains on hold, Rappaport’s colleagues have been developing an intricate system that matches passengers with their luggage at security checkpoints.

“The ‘left-behind’ problem is a key bottleneck — people go through the checkpoint, they leave their stuff sitting there, and TSA has to hold on to it, they have to document it, they have to store it,” says Silevitch, detailing an issue that eats up precious time and slows the flow of passengers. “One of the key goals of our project is to identify whether somebody has left behind a carry-on parcel quickly enough that you can stop the person from leaving and reunite the left-behind object with the owner.”

A mock checkpoint has been built at the Kostas Research Institute at Northeastern’s Innovation Campus in Burlington, Massachusetts. A score of cameras captures images of passengers with their possessions as part of the ongoing CLASP (Correlating Luggage and Specific Passengers) project.

“You’re challenged to, in real time, synchronize the views from the cameras and get a correlation between a person and the luggage that they’re scanning,” Silevitch says.

That system continues to be developed as part of a larger effort to improve security nationwide. In a related upgrade, the TSA has recently installed CT scanners at more than 200 security checkpoints at U.S. airports with plans to add more. The technology, which had already been in place to scan checked luggage, provides TSA workers with 3D images of each bag’s interior.

Overall, passengers continue to express frustration with rules that include forcing them to remove their shoes and limiting the liquids that can be brought through checkpoints. But Silevitch insists those regulations are necessary.

“I think they’re pretty reasonable,” Silevitch says. “I mean, nobody wants to be on a plane that’s threatened.”

Silevitch says he and his Northeastern colleagues are wary of the balance between the yin-yang demands for security and privacy. One example is the desire by some security experts to load passengers’ biometric information onto boarding passes — a move that would strengthen TSA’s ability to screen for potential threats. Silevitch doubts it will ever happen. “There are privacy issues that you have to be very careful about,” he says.

Protecting soft targets

Away from airports, Northeastern is leading efforts to create security for outdoor public areas as well as stadiums, arenas, schools and places of worship where large crowds gather. “How do you protect the millions of soft targets that are in our country?” Rappaport asks rhetorically.

He sets out to answer his own question by describing a cutting-edge network of sensors that may help identify and respond to weapons of mass destruction, including explosives and assault rifles. He envisions outfitting sidewalk light posts with an array of technologies that are being developed by Northeastern and partner universities on behalf of Homeland Security:

- Radar, which is Rappaport’s point of emphasis. “The idea is to combine video and radar to fix on an individual to follow a person in the crowd,” he says. “You cue the radar system to determine if the person is carrying heavy metallic objects.”

- Bomb-sniffing technology. A chemical detector system would identify gun oil or explosives. “It’s like having dogs that can sense very minute fumes,” Silevitch says. “You can’t have a dog at every venue, but you can have the equivalent of a technology dog, and that technology is being developed.”

- Triangulation of cellphones. “Whether the phones are actually transmitting or not, they’re always pinging each other,” Rappaport says. “By triangulating these emissions, you can tell where the bulk of a crowd might be. If there is a panic, you can detect if people are moving in the wrong direction towards the shooter.”

- Drones, which could be outfitted with multiple sensors and deployed to the scene.

- Video, which is the one technology that is ready to be deployed.

“It’s a 10-year project and we’re in the beginning of year three right now,” says Silevitch, adding that researchers are working with U.S. schools (K-12) as well as train and bus terminals to learn their concerns and needs. “In another year or two, we should be able to see some first-generation demonstrations.”

Ian Thomsen is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at i.thomsen@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter @IanatNU.