Published on

How Northeastern’s James Alan Fox

pioneered the study of mass murder

It is because of Fox’s daily efforts to scour and synthesize police and media reports that we know 2,944 people have died in 567 mass killings in the U.S. since 2006. And that was before a man shot and killed at least 18 people at a restaurant and a bowling alley in Lewiston, Maine.

James Alan Fox, a longtime Northeastern professor, is the record-keeper of American mass murder.

It is because of his daily efforts to scour and synthesize police and media reports that we know 2,944 people have died in 567 mass killings since 2006. That was before a man recently shot and killed at least 18 people at a restaurant and a bowling alley in Lewiston, Maine.

Fox presides over the Associated Press/USA TODAY/Northeastern University Mass Killings Database, the longest-running and most extensive data source on the subject.

For all it does to deepen understanding of American gun violence, the award-winning database serves as merely the chalk outline of a four-decade career that has partnered Fox with a U.S. president, an array of law enforcement investigators and TV shows of all kinds.

Fox’s predilection for the worst crimes can be traced back to an exploratory question raised in the late 1970s by his close friend and Northeastern colleague Jack Levin.

“Jack said, ‘Has anyone ever done a study of mass murder?’” recalls Fox in the living room of his Boston duplex, where the walls are adorned with handwritten cards from President Bill Clinton and other memorabilia. “Psychiatrists had written books about their cases. Journalists had written true crime books. But no one had ever done a study of the characteristics.”

They set out to be the first.

“I sent a student to the library to look through journal articles and books — to find something written about this dreaded phenomenon — and she found nothing,” says Levin, professor emeritus and co-director of Northeastern’s Brudnick Center on Violence and Conflict. “I was shocked that no one had ever studied serial murder — there was a much larger number of serial murders than we see nowadays.”

While embarking on their initial five-year study of mass murders, Fox and Levin helped create an industry — both academically and in the media — in the decade of Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy and “The Son of Sam” killer David Berkowitz, among many others.

Their first article was based on data from 42 grisly cases. “We referred to mass killers as ‘extraordinarily ordinary’ because they’re very able to look safe and you’d never suspect they’re dangerous,” says Fox, who would go on to make clever turns of phrase his trademark.

“I never had an interest in mass killing when I joined the Northeastern faculty in 1977. I was a statistician. I was crunching numbers,” says Fox, the Lipman Family Professor of Criminology, Law, and Public Policy at Northeastern. “But then Jack and I got a book deal and a book tour and it just kept steamrolling. We started getting speaking engagements. So we did another book, another book and another book. We were interviewing serial killers in the United States and Canada …”

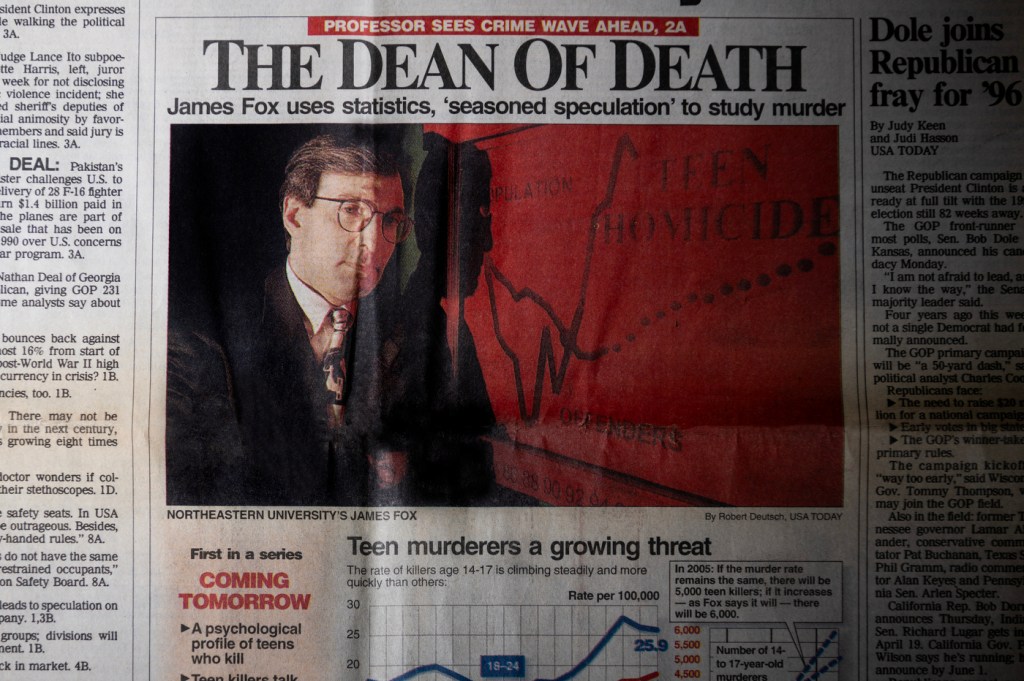

Fox became a media star. There were dozens of appearances on the Oprah Winfrey Show and other national programs. A 1995 USA Today cover story headlined him as the “The Dean of Death” (for at that time he was leading Northeastern’s College of Criminal Justice). Police forces hired him to consult on serial and mass murder investigations. He served as an adviser to Clinton and testified before Congress more than a dozen times. A “Saturday Night Live” sketch about serial murderer Jeffrey Dahmer made allusion to an expert witness from Northeastern University — and to whom else could they have been referring?

A package of five movies was sold to CBS based on the character of James Alan Fox (to be played by the actor Peter Strauss) who teaches a course on homicide at Northeastern while also finding the time to solve murders.

“It was partially true and mostly fictional, of course,” Fox says of the scripts. “But I guess they got flooded with movies about serial murders. So it never got made, unfortunately.”

For more than 40 years Fox has been collecting and analyzing data while offering perspective and well-sourced opinions on gun violence (he is a member of the USA Today board of contributors). He has interviewed the most violent criminals and explored the worst crime scenes while taking controversial stands that have exposed him to criticism from all sides.

Along the way Fox turned out to be built for the role he would create for himself. Because he could take the heat.

We know the portion of the brain that governs our ability to make good decisions doesn’t fully develop until almost 25 years old. So why would we want to put guns in the hands of people who are socially not mature, and whose brains are not fully developed to help them make good decisions?

Fox Proposal No. 1: Establish 25 as the minimum age for owning a gun

Meeting the killers

Kenneth Bianchi, known as the “Hillside Strangler,” had been found guilty of murdering 12 girls and young women when Fox and Levin arrived to interview him at the state penitentiary in Walla Walla, Washington. It was their first meeting with a serial killer.

Bianchi had used fake police badges in Los Angeles to lure 10 of his victims, often with the assistance of his cousin Angelo Buono Jr.

“It’s not so much what he said that was impressive,” Fox says of Bianchi. “It was his demeanor. He first tried to establish control by shaking hands like a vice. But he quickly deferred.”

A prison security guard left the two professors to sit alone with Bianchi for two hours. He neither admitted nor denied his guilt while speaking of serial murderers in the third person, implying an innate understanding without revealing how it had been earned.

“I didn’t feel threatened,” says Fox, who is legally blind. “All the way back to grad school I had been visiting prisons for research projects. Meeting with prisoners wasn’t new to me.”

Their initial book together, “Mass Murder: America’s Growing Menace,” published in 1985, featured profiles of dozens of notorious killers. Levin believes it was the first analytic book written about serial and mass murder. From Bianchi the professors realized with some surprise how easy it could be for someone like him to lure victims by creating an appearance of innocence.

“I was interested in seeing what he was like,” Fox says. “He was quite smooth in his veneer, a typical sociopath.”

“The Silence of the Lambs” and other Hollywood treatments portray interviews with killers as eerie and intimidating. Fox says he has never experienced those feelings.

“It’s the same with crime-scene photos,” Fox says. “I’m able to compartmentalize. They don’t bother me. I don’t get disturbed watching awful videos either. It’s like being a surgeon — if you can’t stand the idea of digging into a body then you’re not going to stand being in that profession.”

The one exception was a bloody scene in Gainesville, Florida, involving a decapitated and eviscerated body. (More on that later.)

“It was a horrific crime,” Fox says. “A couple of times I’ve had a nightmare where I’m lying in bed and I look over and the victim is there.”

During the publicity tour for their first book, Fox and Levin received death-threat letters from the Manson Family, the cult led by Charles Manson that in 1969 killed the pregnant actress Sharon Tate and seven other people in a pair of California home invasions over two nights.

“At that time Manson still had followers who weren’t in prison and they didn’t like something that we had written in the book about Manson,” Fox says of the threat. “We were going to San Francisco to do some appearances and they were in San Francisco, so people asked me if I was worried. I figured we were probably No. 20 on the list of people they hated — and when the first 19 people die, then I’d worry.”

The issue of an assault weapons ban is a nebulous thing. With the assault weapons ban we had in the 1990s, they listed certain firearms as assault weapons — and then the gun manufacturers simply modified them and gave them new model numbers.

Fox proposal No. 2: Ban large-capacity magazines

It’s the ability to continue to pull the trigger and refire without reloading that is the issue.

Blindness, bullying and the Vietnam era

“I was born premature by two and a half months,” Fox says. “It was the same thing that happened with Stevie Wonder. At that time they would put preemies in an incubator but they wouldn’t protect the eyes. The oxygen was bad for the retina. It caused blindness.”

His condition is known as retinopathy of prematurity. Decades later, during cataract surgery, Fox was fitted with eye implants. His right eye has been corrected to 20/100, enabling him to see from 20 feet what a person with average vision can see from 100 feet. His left eye is barely functional.

Unable to access traditional books, he reads by sitting close to a computer screen or by enlarging the fonts of an iPad.

“Six months after I was born,” says Fox, “they discovered the problem and they started covering the eyes of preemies.”

His eyesight created social problems for Fox while growing up in suburban Boston.

“I was bullied as a kid,” Fox says. “Back then they didn’t have the technology to make thin lenses, so my glasses were really thick. I was one of the only Jewish kids at my prep school. I was even bullied at Hebrew School. I was very heavy. So I would get pushed around. There weren’t any broken bones. But I was mistreated.”

At the insistence of his mother — “she never believed in my seeing myself as handicapped” — he played catcher, the lone position in baseball that could withstand the absence of depth perception. He was a defensive lineman in football.

One summer during high school he went on a crash diet of mostly carrots, developing carotenemia, a condition that for a time turned his skin yellow-orange. He shed the excessive weight while eventually normalizing his diet. He replaced his glasses with contact lenses and grew his hair longer.

“And then I became popular,” says Fox, who goes by Jamie among family and friends.

It was an extraordinary time to be a college student amid the Vietnam War, the hippie movement and easy access to marijuana.

“I was political as an undergrad,” says Fox, who attended the University of Pennsylvania. “I went to anti-war rallies. At Penn we had events called ‘Sleep with RALPH’ — the Radical Association for Love, Peace and Happiness. We would sit out in the college green and smoke dope and talk about the war.”

The hippie era influenced his unlikely career choice.

“I’d always wanted to be a teacher — a math teacher — and as a freshman I was a math major,” Fox says. “After one semester I gave it up because people were dying in Vietnam: The fourth derivative seemed meaningless.”

He decided to study music based on his interest in the mathematics of composition. That lasted for a semester when he realized the other music majors “knew all these composers that I’d never heard of,” says Fox, who would graduate in three years. “So I switched to sociology — something to help society.”

It was during Fox’s final semester that he developed his defining interest in criminology. After a year of teaching in Michigan he returned to Penn, where by age 25 he had earned master’s degrees in statistics and in criminology as well as a Ph.D. in sociology (the latter two earned with distinction).

There are no simple answers for why someone of his talent would be devoted to pioneering our understanding of murderers and the murders they commit. Fox rejects the pop-psychology theory that his childhood difficulties readied him for the trauma he would make a career of studying and analyzing. “I don’t see the connection,” he says.

But Fox does acknowledge that his blindness forced him to chart his own path.

“In elementary school I was in the lowest math class,” Fox says. “I got terrible grades. I wasn’t doing it ‘the right way.’ It was because I couldn’t see the blackboard, so I had to devise my own methods for solving math problems. And I still do that.”

A permit to purchase involves a much more thorough background check than the federal one. In Massachusetts and several other states that require a permit to purchase, those states have lower rates of mass killing. That’s because the local police [who issue the gun permit] know a lot more about people than what their official record might show.

Fox proposal No. 3: Gun buyers should apply for permits

Controversial findings

In the 1980s Fox was asked by the Detroit Free Press to analyze a series of Detroit murders committed by teenagers with guns. Relying in part on a database of every U.S. homicide that he had been maintaining since 1976, Fox set out to study violence among young people.

That research resulted in calls by Fox for an increase in after-school programs. Responding to a rise in the homicide rate among young people in the late 1980s into the early ’90s, Fox publicly predicted more violence to come — unless the trend was mitigated by a coherent investment in kids.

“I used very colorful terms,” Fox says. “I said that we were at the calm before the crime storm. I said if we don’t act now we may see a bloodbath — not literally of course. My intention was to use very provocative language to get the attention of policymakers so they would reinvest in prevention programs.”

He was surprised by what came next. His recommendations for prevention programs were ignored. And yet the juvenile crime rate shrunk because, according to Fox, “virtually every state passed draconian laws to try juvenile murderers as adults. All of a sudden, starting in the ’90s, thousands of kids were being tried as adults every year.”

Fox acknowledges his forecast was wrong — in large part because juvenile murderers were reclassified as adults.

“But I don’t apologize,” Fox says. “Punishment is closing the barn door after the horses have left. The fact that lawmakers decided to respond by ignoring prevention and spending on punishment — that’s on them, not me.”

Though the homicide rate overall continued to fall in the 2000s, research by Fox showed that the rate was rebounding among young Black males.

“I’m very proud that a lot of what I’ve done over the years has had an impact on policy,” Fox says. “I truly believe in data analysis and that you back things up with evidence. I don’t mind the limelight and I understand that you get criticized.”

His stance on crime by young people drew the attention of the Clinton administration in the 1990s. Fox was appointed to brief Attorney General Janet Reno and prepare a special report on trends in juvenile violence. Reno asked Fox to give a keynote address on behalf of a U.S. delegation attending a summit in the U.K., where Princess Anne delivered a matching speech for Britain.

Fox would meet several times with Clinton, beginning with a large working dinner at the White House where he was assigned to sit between the president and his chief domestic policy adviser, Rahm Emanuel. Their next White House meeting was more intimate, coming hours after Clinton had given a deposition on his relationship with Monica Lewinsky. Hillary Clinton was among the half-dozen at the table.

“It was an icy relationship between Bill and Hillary,” recalls Fox, whose “prime time for juvenile crime” research findings were cited by Clinton in a State of the Union address.

His influence was enduring: On his way to earning Northeastern’s prestigious Klein Lectureship in 2008, Fox received a letter of recommendation from future President Joe Biden, before whom he had testified multiple times while Biden chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Fox has testified in dozens of high-profile civil cases and helped support a variety of homicide investigations. During a 1990 live appearance on the nationally televised Phil Donahue talk show in Gainesville, Florida, where five college students had been murdered in a span of four days, Fox suggested that police had arrested the wrong person — a University of Florida student, Edward Lewis Humphrey.

“Phil Donahue asked, ‘Professor Fox, why did Ed Humphrey do it?’ I said, ‘I don’t think he did,’” recalls Fox. “Donahue lectured me: ‘How dare you say that! This community wants to believe and know that the killer is in custody and they’re no longer in danger. And you have the audacity to come thousands of miles away, being a professor at some ivory tower university, and tell them that this kid is not the killer. How do you do that?’”

Immediately following the broadcast Fox was approached by the investigating task force. He explained to the detectives that the student in custody had behaved far too impulsively and recklessly to pull off such a gruesome and yet meticulous series of murders (including one that had become the source of Fox’s nightmares).

Fox recalls the task force leader nodding in agreement as he replied, “We just got the results of the lab work and he wasn’t the killer.”

The task force hired Fox, who months later would confirm similarities to a triple murder in Shreveport, Louisiana. The new suspect was Danny Rolling, to become known as the “Gainesville Ripper,” who was in jail for robbery in Ocala, Florida; his case would inspire the “Scream” horror movies.

“We needed to get physical evidence such as blood and pubic hairs — the cops called them ‘pubes and tubes,’” Fox says. “The problem was he was in jail. By ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court you’re not allowed to get physical evidence from an inmate even if they offer it because it’s implicitly a coercive environment.

“As luck would have it, Rolling had an impacted wisdom tooth and the tooth was pulled in the jail by a dentist who threw the tooth into the trash. Anything that’s in the trash no longer belongs to you. So we took the tooth, the whole tooth and nothing but the tooth and sent it to the lab.”

Searching back through the records of the year-long investigation, detectives would find a tip they had received early in their investigation from an 80-year-old woman in Pennsylvania. Fox recalls that she claimed to have been watching a TV show about the murders when she realized in a flash of intuition that the killer’s name was “Rollings.”

“We then investigated that woman, thinking that maybe she had some connection,” Fox says. “I don’t believe in psychics. But to this day I don’t know how she came up with the name.”

If I had my way we wouldn’t have a Second Amendment. But we do.

Fox proposal No. 4: Account for the realities of American gun violence

Understanding that, we still have the ability virtually to eliminate mass shootings as a country. We could round up all the guns. We could round up all the people who scare us, who write ugly things on the internet and so on. But we’re not going to do that because we value our personal freedoms.

Unfortunately, mass shooting is one of the prices we pay for those freedoms that we enjoy.

A sense of balance

The shelves of Fox’s den are filled with the 18 books he has authored alongside dozens of editions of the prestigious Journal of Quantitative Criminology, for which he was the founding editor in 1985.

“The field has become very quantitative since then,” he says of the journal’s influence. “So that was a big accomplishment for me.”

Though Fox no longer teaches classes at Northeastern, he is of no mind to retire. “If anything, he has been more successful these last few years than he ever was before,” says Levin, referring to the mass killings database as well as more than 300 op-eds that Fox has written for USA Today and other publications.

Even now, Fox occasionally conducts a walking tour of Boston’s most violent historical sites, which he refers to as the “Unfreedom Trail.” He also leads duck boat “Murder and Mayhem” tours of the city.

The Washington Post is planning its own mass killings website based on his data, Fox says.

Despite the gun-related deaths of more than 48,000 people in 2021, a U.S. record, relatively little government data on firearms is available for researchers like Matt Miller, a professor of health sciences and epidemiology at Northeastern who studies injury and violence prevention. Miller credits the Fox database with elevating public awareness.

“Professor Fox’s dedication to making data available to the public helps foster more informed quantitative discussions around firearm-related issues,” Miller says. “It allows journalists and interested citizens to poke around the data and think more deeply about the issues than would have been the case if Fox had confined his scholarship to the academic press.

“Jamie’s work represents a commitment to encouraging informed debate that can only help advance more thoughtful, empirically grounded discussions about how to mitigate the harms of readily available firearms in the United States.”

Fox says he has consciously fulfilled the Northeastern approach of making his work accessible beyond the academic community.

“The university has gotten letters complaining about me with people saying I should get fired because of my point of view on guns, the death penalty and other issues,” Fox says. “But the university has never tried to establish a style for me. Quite the opposite. They have always been very pleased with my being out there and being very visible in the public domain and promoting research, which obviously promotes the university.”

Fox’s father earned a Northeastern degree in electrical engineering prior to serving in World War II. “Not only has the institution supported my career for the past 46 years,” says Fox, “but my wife, Sue Ann, and I raised three children — a corporate lawyer, a Massachusetts judge, and a JetBlue pilot — who made the most of their Northeastern educations. My hope is for one or more of our eight grandchildren to make their way to Huntington Avenue for college.”

His groundbreaking work has forced Fox to balance empathy with a pragmatic approach to crimes that have devastated millions of victims and their loved ones.

In 2012, as an expert correspondent for NBC News, he stood across the street from Sandy Hook Elementary School after 26 people, including 20 children who were 6 or 7 years old, had been murdered by a young man with an assault rifle. Last December, on the 10th anniversary of the attack, he returned to visit a new memorial that had been created for the victims.

Aided by his white mobility cane, Fox made his way to a plaque that greets visitors. A stranger asked him, “Would you like me to read it to you?”

“Yes, please,” Fox said.

“‘… Mere words cannot match the depths of your sorrow, nor can they heal your wounded hearts,’” the man said, quoting a passage from President Barack Obama’s remarks at the time of the killings. “‘I can only hope it helps for you to know that you’re not alone in your grief, that our world too has been torn apart, that all along this land of ours we have wept with you.’”

Fox held his breath for a moment. “Thank you,” he said, smiling in gratitude, and with the tapping of his cane he made his way down the hill.

Ian Thomsen is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at i.thomsen@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter @IanatNU.