Published on

The stories of Black Londoners from centuries past come to life through Northeastern research project

By researching the lives of Black Londoners from 1560 to 1840, the Mapping Black London project challenges how we think about London’s diverse history

LONDON — Every time a student walks to the Devon House campus at Northeastern University London they pass what was once a hub of Black life.

Just off the River Thames on the east end of the city, the campus is flanked by London’s only marina, St. Katharine Docks. But before the 19th century, these docks were nowhere to be found; instead, there stood a 12th-century parish church and hospital.

Now just a spot on the water, the location was once a hot spot for Black Londoners who were reaching some of their lives’ biggest milestones: a man named William Butcher was baptized at the parish at 40 years old in 1783; an unnamed man thought to be from India was buried there in 1782; and in 1702, Adam, “a Black and Servant to Mr Lansdon,” was baptized there.

“People were flocking to this area to get married or to get baptized,” says Libby Collard, a recent graduate from Northeastern University London. Collard thinks the parish may have been the location of a Black minister who was known for marrying people of color.

When the church was demolished in the 1820s to make way for the docks, William Butcher, the unnamed Indian man and Adam were all lost to history.

Until now.

Thanks to a team of historians at Northeastern University London, the stories of everyday Londoners of color like those at St. Katharine parish are being unearthed and re-incorporated into the historical record. In turn, they are creating a more holistic view of the city’s history, one that includes its vibrant Black life.

Using archival data from the London Metropolitan Archives, which carries records dating to 1067, students and faculty working on the Mapping Black London project have unearthed 3,302 records of people of color who lived in London from 1560 to 1840. A few dozen of the Londoners are highlighted in what is now an exhibit at the LMA called Unforgotten Lives.

The records — including baptisms, marriages, deaths and images — show the everyday lives of Black Londoners in all their diversity. Contrary to stereotypes that Black people formed a servant class, the exhibit depicts people of color — including those of African, Caribbean, Asian, Indigenous descent — from all walks of life, from the very famous to the anonymous. Londoners of color owned businesses, they got married, they had children and they moved around the country and the world.

Getting to over 3,000 entries was no easy task, however. The project was a labor of love for Northeastern professors Olly Ayers in London and Nicole Aljoe in Boston. They began by mapping the life of Ignatius Sancho, a Black Londoner who rubbed elbows with some of the city’s elites. Once they had mapped Sancho’s life, the professors and their research assistants began perusing LMA documents to piece together the lives of other Black Londoners, using the data to create a heat map of Black London.

It was a laborious and time-consuming effort. Old records are rife with incorrect information, misspelled names and indecipherable handwriting. Many documents have been lost to history due to fires and other incidents, leaving large gaps in the archives.

But what was there allowed the team to do something extraordinary: bring forgotten lives back into the historical record.

“It still shocks me that I can go into the archive and find something that nobody else has found before,” Collard says.

She’s stumbled upon records that it’s likely nobody has seen in hundreds of years, she says. She would get so excited that she would then go home and tell her roommates. “When I’m researching something, I just want to tell everyone if I’ve found something exciting,” she says.

At the same time, the project changed the way the team thought about London and its history.

For one thing, there’s a misconception that during this time Black people were sequestered in certain areas of London. However, their data tells a completely different story. Their heat map shows their records clustered into parishes, which Collard compares to community centers, where people were baptized, buried and married.

“Different sections of the city come up redder than others,” Collard says. Still, “one of the main things that came out of that mapping was that Black people were all over London. There weren’t distinct sections.”

This also dispels the notion that Black history and British history are separate — in fact, people of color walked the same streets as other Londoners on a daily basis, in a truly diverse community.

“We’re looking at this idea of London as a community,” Collard says. “This is what our history is, this is what London is like.”

This had a personal impact on Odile Jordan, a third-year philosophy student at Northeastern University London who signed on to the project over a year ago. “Knowing that the presence of people of color in London has gone back so far, it’s an affirming experience, in the sense that your presence in the streets of London as a Black person or a person of color is not unprecedented,” Jordan says. “You don’t belong any less than white people do.”

Like Collard, Jordan was surprised at how this experience affected her. “I realized that somebody hundreds of years ago wrote down this person’s name,” she says. “And I am physically touching the traces that they left behind. That was such a profound experience.”

Living in London gave the project even more weight — Collard, Jordan and the rest of the team were able to trace footsteps of the Black Londoners they found in the archives, and explore the streets where they lived, allowing them to reconnect with their history in a new way. When Collard finds a site that’s near her, she says, she likes to go to visit it. She passes the former home of Anne Sancho, wife of Ignatius Sancho, on her way to the university every day.

“Those kinds of things do make you see the city in a different way,” she says.

Jordan agrees. Visiting the places they’ve studied “makes you really appreciate the extent to which this history has shaped London,” she says. “It helps you appreciate the importance of knowing about the history of your surroundings.”

The Unforgotten Lives exhibition will run until March. Meanwhile, the research continues, and it continues to have a profound impact on the team.

“It’s part of what we think of far, far history,” Jordan says. “But it’s not; it’s right in front of me.”

The Mapping Black London project has rediscovered the lives of many people of color living in London going back centuries. Here are the stories of some of those “Unforgotten Lives.”

Billy Waters

Billy Waters was an American Revolutionary War veteran who may have earned his freedom from slavery by fighting for the British.

But he is best known as a talented violinist and busker who later became a fixture outside London’s Adelphi Theatre in the West End in the 1810s and 1820s. It is thought that he supplemented his tiny naval pension through busking.

Waters became such a well-known fixture of London life that he was caricatured in print culture, including his stump leg and feathered cap, in the publication Live in London.

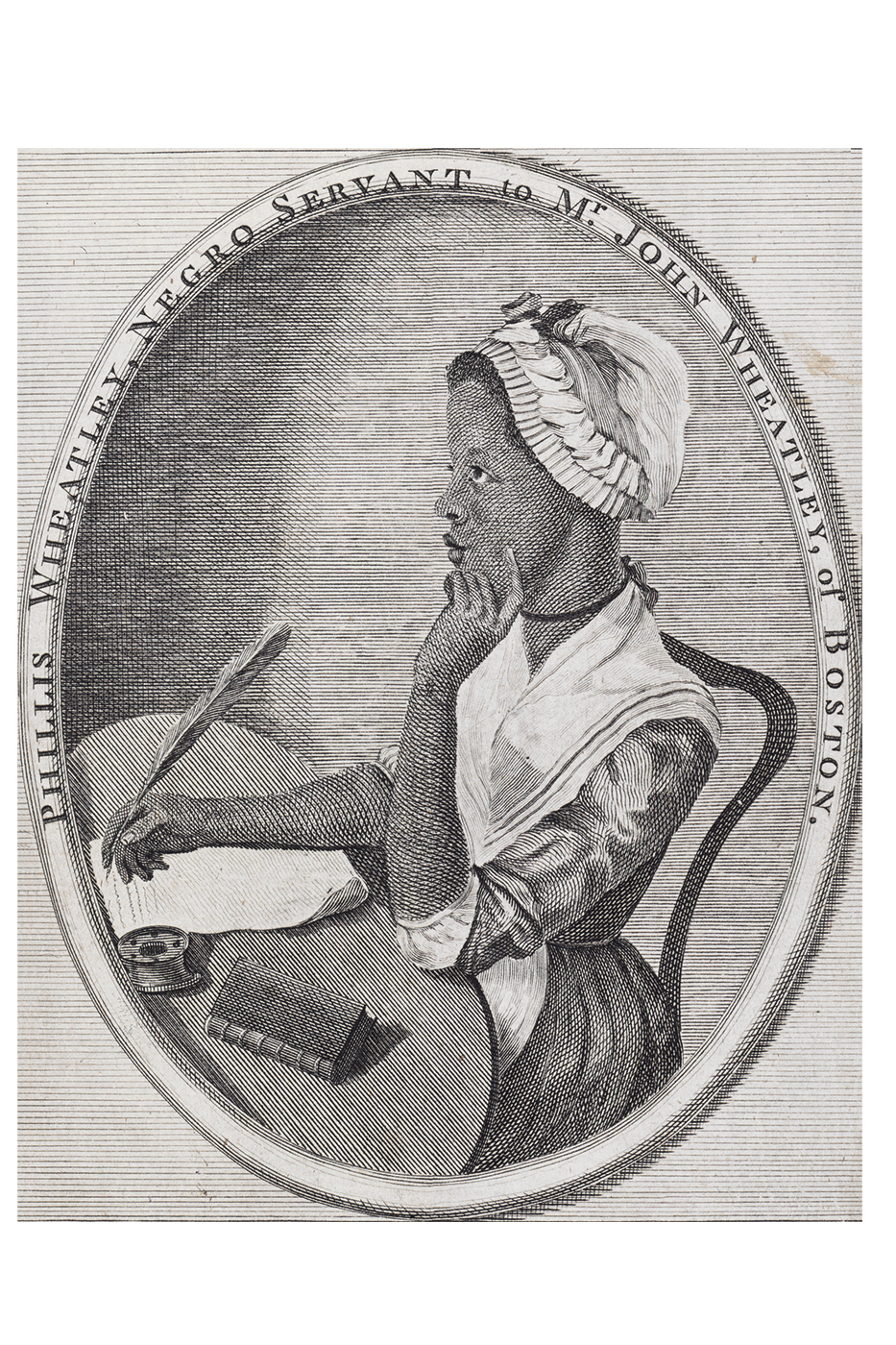

Phillis Wheatley

“In every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of Freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance.”

A staple of American literature, Phillis Wheatley is well known as the first African-American female poet to be published. But she is also known for her travels to London in 1773, where she was introduced to elites of London society.

Originally born in West Africa around 1754, Wheatley was a slave for the Wheatley family, who taught her to read and write and encouraged her poetry writing. Wheatley’s poetry collection “On Various Subjects, Religious and Moral” was published by a bookseller in Aldgate in London.

Sake Dean Mohamed

London got its first Indian restaurant thanks to Sake Dean Mohamed, who opened Hindostanee Coffee House in Marylebone on 34 George St. in 1810.

Unfortunately, it went bankrupt, and he moved to Brighton in 1814. A serial entrepreneur, Mohamed started two bathhouses in Westminster in 1838. He also wrote a book of letters to a friend, in what is considered the first book published in English by an Indian person.

Ellen Craft and William Craft

“I had much rather starve in England, a free woman, than be a slave for the best man that ever breathed upon the American continent.”

Ellen Craft and William Craft’s fascinating story begins in Georgia in the United States where they were born in 1826 and 1824, respectively.

They were able to escape enslavement in 1848 thanks to some creative costuming — Ellen pretended to be a white male plantation owner with William as her slave. The ruse worked, and the couple was able to travel north to Boston.

After the Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850, however, their life in the U.S. became precarious. They escaped to Liverpool and later to London, where they lived for 19 years. There they became members of the London Emancipation Committee, and their home became a headquarters for Black activism. Ellen also toured, giving lectures on women’s rights.

Later, they returned to Georgia to establish schools to educate freed slaves. The couple told their story in a book called “Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom.”

Robert Wedderburn

“I visited my father, who had the inhumanity to threaten to send me to gaol [jail] if I troubled him. … He did not deny me to be his son, but called me a lazy fellow and said he would do nothing for me. From his cook I had one draught of small beer, and his footman gave me a cracked sixpence.”

An activist, preacher and writer who demanded rights for Black people and workers, Robert Wedderburn was imprisoned several times.

Born in Jamaica to a slave and her enslaver — who, later, refused to support him financially — Wedderburn managed to move to England in 1780. There, he became heavily involved in politics and joined radical political organizations.

He published his autobiography “The Horrors of Slavery” in 1824.

Ann Duck

One of the women featured in the exhibit was a hardened criminal known for assaulting and robbing drunk men. Ann Duck was born in 1717 to a father who was a master sword fighter. Things went south for her following his death, and she worked in a brothel and as a sex worker. She was imprisoned multiple times, including twice at the Old Bailey in 1743. It is thought that the men she assaulted were too afraid to report the crimes.

The year 1744 proved to be Duck’s downfall. One man died during a robbery and she was a part of a violent mob that year, leading to her trial at the Old Bailey. She was sentenced to death and hanged.

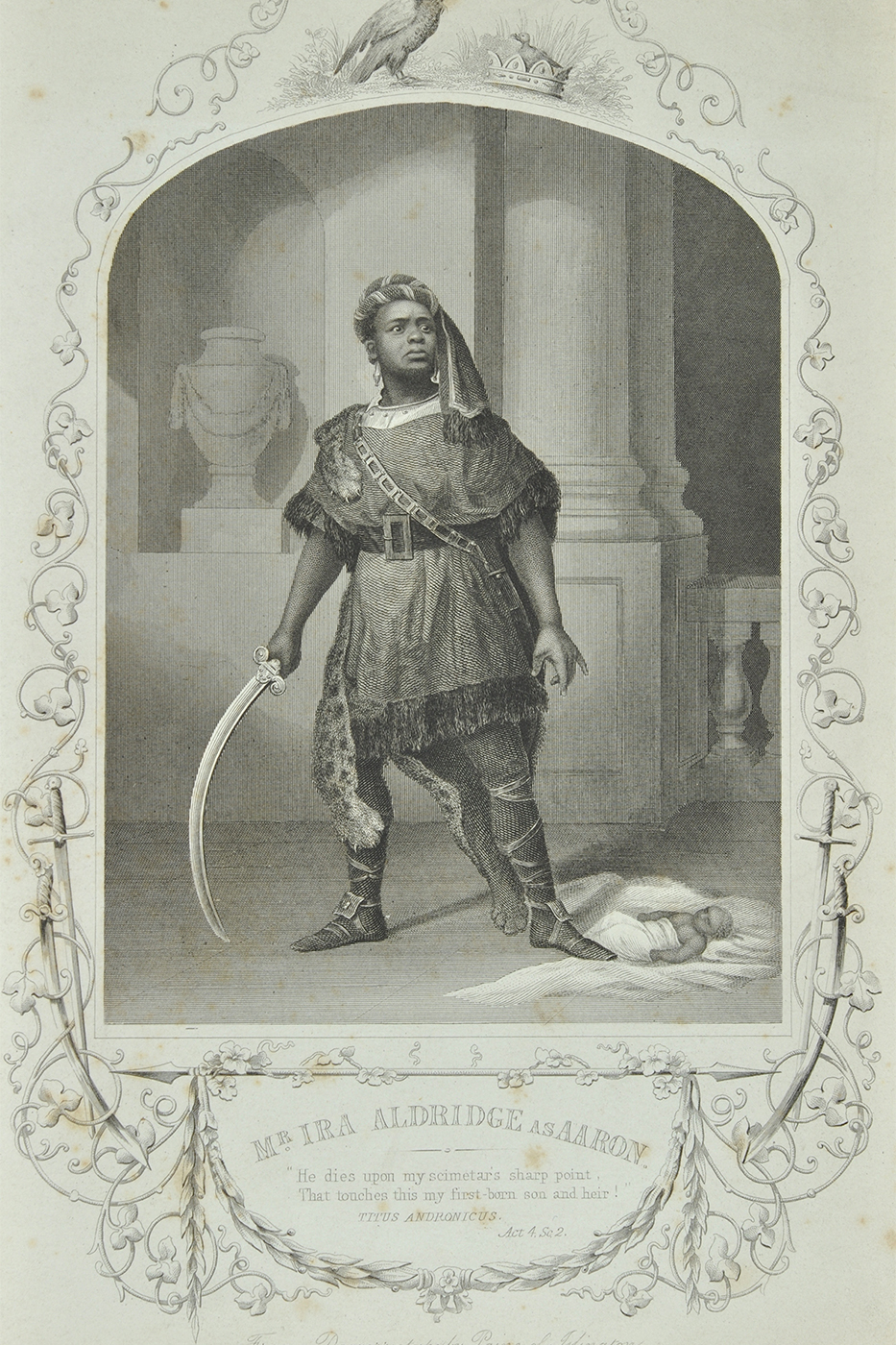

Ira Aldridge

Frederick (Ira) Aldridge was the first Black actor to play Othello at the Royalty Theater in 1825. It was also his debut, at only 17 years old.

Born in New York, Aldridge was a member of the first resident African-American theater in the United States, the African Grove Theater, which he joined in 1821. He moved to London for more opportunity as an actor in 1824, and made his famous debut the following year. After Othello, he toured England as an actor, playing Shakespearean and other roles.

John

The oldest entry in the project is John, a Black man who was baptized on May 6, 1565, at St. Mary the Virgin Aldermanbury and died the next year. The church was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and again during World War II. Nothing else is known about John.