Published on

Nearly 50 years later, famous photo is a ‘teaching tool,’ not just an ‘artifact of America’s past’

Photographer Stanley Forman and victim Ted Landsmark, a distinguished professor at Northeastern, reflect on the 1977 Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph, “The Soiling of Old Glory.” Even today, Landsmark says, it can be used to spark discussion about race.

You probably know the picture.

For millions of people, the image of a white teen using the American flag to attack a Black man on Boston City Hall Plaza on April 5, 1976, encapsulated the hatred that embroiled the Boston busing crisis and the tenuous state of contemporary race relations in the United States.

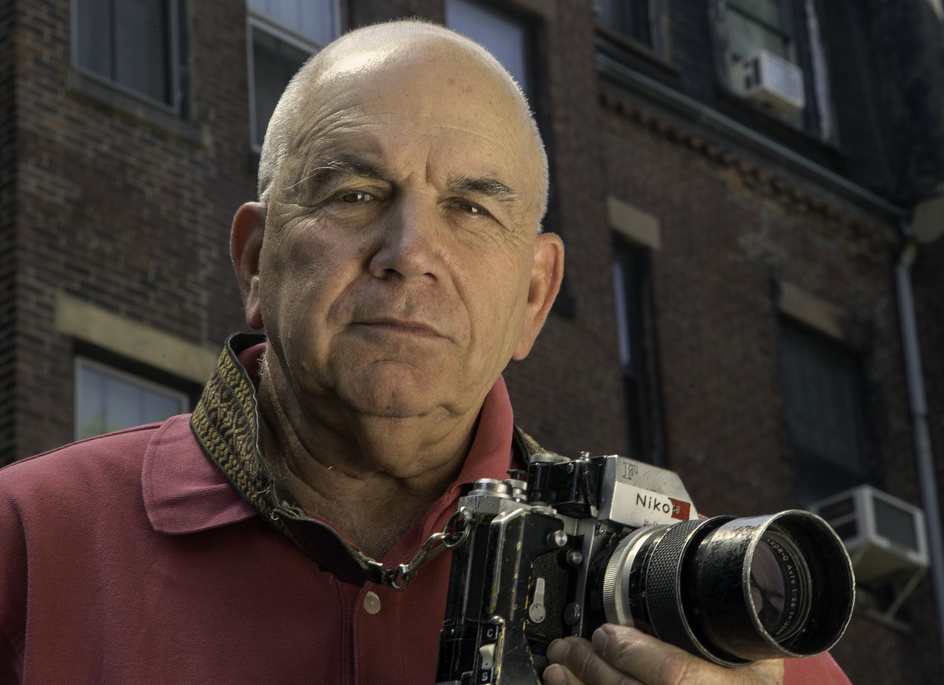

But photographer Stanley Forman didn’t realize he captured something iconic until hours after the event.

“To me it was just another racially charged demonstration,” Forman says. “I know it sounds foolish, but it was a few hours later when I realized the significance of the picture. … I just knew it was an anti-busing demonstration that went to shit.”

Ted Landsmark, the victim of the attack, meanwhile, didn’t immediately realize that a photograph had even been taken.

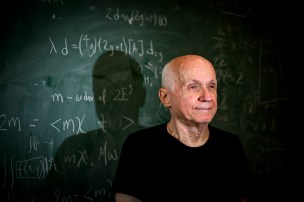

“It wasn’t until after the event that I realized there were any media present,” says Landsmark, a distinguished professor of public policy and urban affairs and director of the Kitty and Michael Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University.

Joseph Rakes, the attacker 47 years ago, did not respond to a request for an interview.

The photo, called the “The Soiling of Old Glory,” appeared in the Boston Herald American newspaper the next day, was distributed around the world and won the 1977 Pulitzer Prize for Spot Photography.

This image is a reminder of the work that needs to be done now to address issues of racial injustice, discrimination and disparities, some of which are worse today than they were then.

Ted Landsmark, distinguished professor of public policy and urban affairs at Northeastern

It has since served as both a reminder of the city and country’s racist past and as a prescient symbol for the present, often reappearing in the public eye when issues regarding the American flag and racial protest arise. In fact, Landsmark and Forman are scheduled to be on CBS Sunday Morning on June 18 to talk about the photo.

As for that moment in 1976, Landsmark was heading to Boston City Hall to meet with the city planning agency to advocate for increased training and job opportunities for local residents and people of color in neighborhood public works projects.

He had been involved in the social justice movement since before high school and visited Selma, Alabama, and Atlanta as a college student. He also attended civil rights and anti-war demonstrations while studying law at Yale University, where he was the political editor of the Yale Daily News.

But he “had no idea” an anti-busing protest would be going on at about the same time as his meeting. Nor did he even see the demonstrators until they both approached a corner from the opposite directions.

“I quickly realized that if I just kept walking straight, they would turn the corner and head off wherever they were going—it turned out that was the federal courthouse—and I could just continue onto my meeting,” Landsmark says.

Meanwhile, Forman saw the demonstrators were on course to intercept Landsmark and had his camera at the ready.

“I’m big on breaking news, so I like to think I have common sense and I anticipate, and when I look around, I’m trying to capture a picture that portrays what I’m doing,” Forman says.

The attack wasn’t immediate.

“What the photo shows is a significant number of the young people had in fact already passed me as of the time the flag bearer and others who attacked me circled back to attack me from behind,” Landsmark says.

But the attack was dramatic. A demonstrator hit Landsmark from behind, breaking his nose. Rakes, the flag bearer, swung the flag at Landsmark and missed his face by inches. In all, the attack lasted less than 10 seconds.

Forman was shooting away.

“You go there, you look around, you size up the scene, and I put myself in a position where I’ll have the best picture or a good picture—I always want to have the best picture—or where I’ll get a good picture, and it will be the best,” Forman says.

He got a picture that was the best.

He also angered the demonstrators and had to be escorted back to his car by the deputy superintendent of the Boston Police.

“I was very fearful that day, and many days after that,” Forman says. “I became, ‘there he is.’”

Landsmark, meanwhile, also had attracted attention; there was media awaiting him as he left the hospital.

But his civil rights and social justice involvement had prepared him.

“I’d given thought to what I might say if I were ever in a challenging civil rights situation and asked to respond to that moment,” Landsmark says. “I had been previously harassed by people opposed to civil rights, I had been a part of mass arrests during anti-war demonstrations, I was aware of activists who had been beaten and/or killed because of their commitment to achieving social justice, and I was aware that a moment could come in my life when I might be called upon to make thoughtful remarks as an activist and advocate for racial justice.”

Nearly 50 years later, he continues to advocate.

“The point is there’s a tendency to look at the photograph as evidence of how patriotic symbols can be used for divisive purposes throughout American history,” Landsmark says. “I also believe that this image is a reminder of the work that needs to be done now to address issues of racial injustice, discrimination and disparities, some of which are worse today than they were then: residential segregation, school segregation, lack of access to affordable housing, are all issues that are statistically more heinous and complex today than they were at that time, despite the progress that has been made in bringing people together around voting rights or public accommodations.”

In fact, Landsmark keeps a copy of the photo in his office at Northeastern, using it as a “teaching tool” when asked about it.

“While the photo stands for a moment in time in and of itself, it is also a starting point for deep conversations on how we as ethical people can better share the resources that we’re able to develop through our talents, connections and hard work,” Landsmark says. “It’s a teaching tool that is a forward-looking platform for discussions of ethics and racial and social justice rather than being an artifact of Boston and America’s past.”

Forman, meanwhile looks at the picture—which would be his second of three Pulitzers; he also won in 1976 for a series of a woman and child falling from a collapsing fire escape, and shared a prize with the staff of the Herald American in 1979 for coverage of the Blizzard of 1978 —and he sees pure hatred. In fact, he views the picture as one in a series of photos that he took that day.

“When I look at the faces, and the rage, and if you look at all the pictures, how some people in the picture went from point a to point b. It was so hatefully charged,” Forman says. “Everybody calls it a picture of racism, it’s a picture of hate—the whole sequence of hate.”

And as Landsmark continues to advocate, Forman continues to shoot photos.

“Scanners are my music,” Forman says during the interview, as police scanners screech in the background. “I hope I can chase news until I can’t.”

“I’m still looking for that next great picture,” Forman continues. “I think there’s another banger out there for me.”

And if another such a situation arises, Landsmark urges the next generation to be prepared.

“You never know when a moment will come when you need to say and do the right thing in order to further a sense of justice,” Landsmark says. “So, that means you have to be ready all the time.”

Cyrus Moulton is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at c.moulton@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @MoultonCyrus.