Published on

How the legendary rock band Rush was discovered by a former Northeastern DJ

In 1968, Donna Halper became the first female DJ at Northeastern’s radio station. In 1974, as a DJ in Cleveland, she gave an unknown band a chance. Now 76, she’ll be inducted into the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame.

Donna Halper dropped the needle onto the record, ready to give the unknown band a chance.

She’d never heard of Rush—really, no one had. But a Canadian record promoter had sent her the Toronto bar band’s self-titled, self-released album. His label had turned the band down, but he thought they had potential. Maybe she’d agree.

It was 1974, and Halper, then 27, had just gotten her big break. Just months after earning her third degree from Northeastern University, Halper had left her native Boston to become music director of WMMS-FM, a rock station in Cleveland. Her job: find new music, raise the station’s ratings, and increase its importance in the music industry.

Halper searched Rush’s album and chose a long cut called “Working Man.” A guitar riff—slow, ultra-heavy, Led Zeppelin-esque—introduced these lyrics:

Well, I get up at seven, yeah

And I go to work at nine

I got no time for livin’

Yes, I’m workin’ all the time

“Cleveland was a factory town back then,” Halper recalls. “I said, this song is going to resonate with our audience.” She had a DJ put it on the air that night. Listeners started calling. Some asked if it was a new Led Zeppelin song. Others asked, “Can you play it again?”

Requests poured in. Halper put “Working Man” in heavy rotation and called Rush’s manager in Toronto. “I said, ‘We need more copies of this.’ He said, ‘You do? We can’t get arrested in Toronto with this. Nobody wants our album.’” He shipped a box of copies to Halper, who brought it to Record Revolution, an imports-friendly record store in Cleveland Heights.

That’s how Halper gave the band Rush their big break—which eventually led to the group selling 40 million records in a decades-long career. When Mercury Records released that first Rush album in the U.S. later in 1974, the band credited her in the liner notes: “With Special Thanks to Donna Halper of WMMS in Cleveland for getting the ball rolling.”

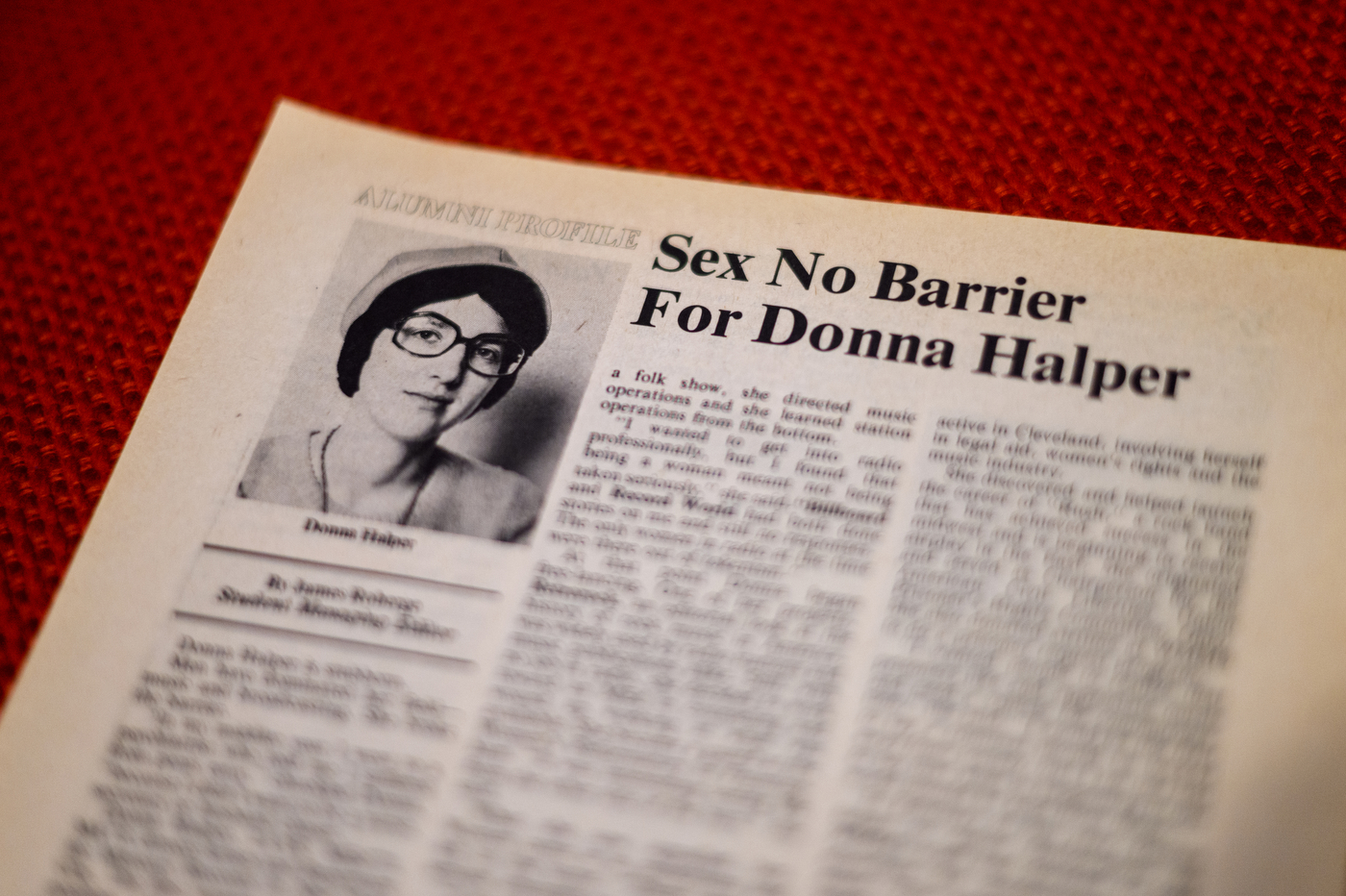

Along with Rush’s breakthrough, Halper has broken down many barriers for herself, first at Northeastern, and then throughout her pioneering career. In 1968, as a Northeastern senior, she became the first female DJ and music director on the university’s radio station, now WRBB. In the 1970s, after years of striving, Halper broke onto the air as a DJ in Cleveland, New York City, and Washington, D.C., before returning to Boston.

And after decades as a radio consultant, music historian and media professor who earned a Ph.D. at age 64, Halper—now 76—will be inducted into the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame, receiving the organization’s Pioneer Award, on June 8.

“I’m very gratified, but still shocked,” Halper says of her induction. “I wish my parents had lived to see it. I wonder what they’d make of it. Because it’s a totally different world.”

Halper, born in 1947, grew up in Boston’s Roslindale neighborhood. “I knew I wanted to be a broadcaster from the time I was a kid,” she recalls. “But the options for girls back then were teacher, nurse or secretary. I knew I did not want to be any of those, but I got tired of arguing with my parents about it. I came to Northeastern expecting that I would study education, but ready to fight for the right to be in broadcasting.”

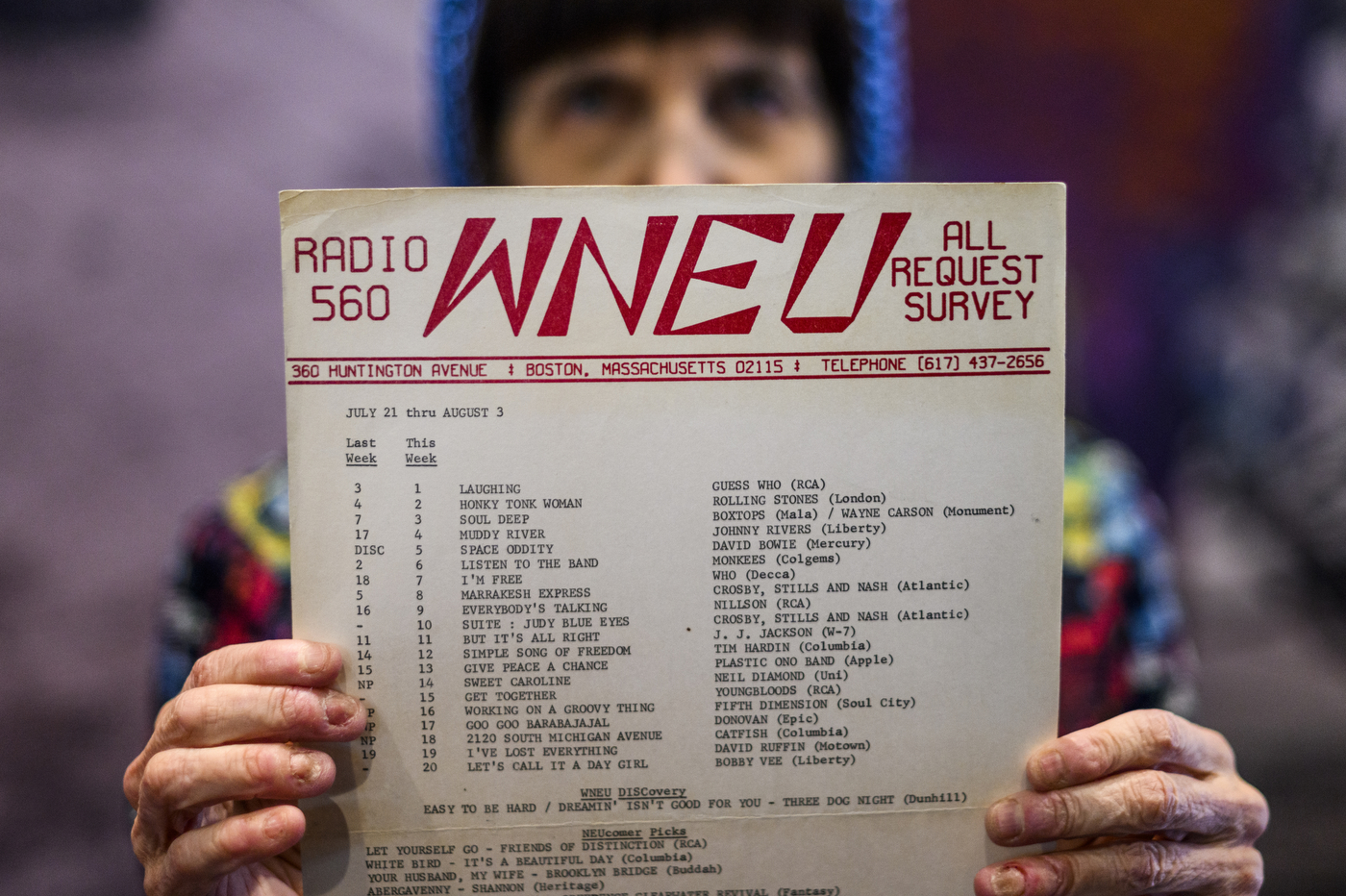

When Halper arrived at Northeastern in fall 1964, she joined the staff of the campus radio station, then named WNEU, and told the all-male student managers that she wanted to apply to be a DJ. “They said, ‘You can’t be a DJ. You can segue records, you can play records, but you can’t talk on the air.’ I’m like, ‘Why not?’ He said, ‘Well, girls don’t sound good on the radio.’ And I said, ‘Well, how many have you had on the air?’”

For a while, Halper lived with the Catch-22, going on the air only in skits, doing a fake British accent and other imitations. But by spring 1965, her DJ dreams blocked, she left the station and focused on earning an education degree. She chafed at the gender rules enforced back then. She’d often come to campus straight from her job at a warehouse, with no time to change into a dress as required, and she’d end up getting sent to a dean.

But as a senior in the fall of 1968, encouraged by a professor who mentored her, Halper returned to WNEU and tried again. That time, the new program director gave her an audition, then put her on the air as a DJ in November.

“And that changed my whole life,” Halper says. She debuted a folk music show called Full Circle on Nov. 1, 1968. She still has her handwritten tentative playlist for that first day: It starts with “V’La L’bon Vent” (Here’s the Good Wind), by the Canadian folk duo Ian & Sylvia. A photo of Halper that ran in Northeastern News that month, captioned “Lady Jock,” shows her working in WNEU’s broadcast booth, between a turntable and a black request phone. She’s wearing round, black-framed glasses and a patterned pullover; headphones sit over a wide headband holding back her long dark hair.

Halper went from one night a week to three to five and became WNEU’s music director. “I still have some of the fan mail that people sent me,” she remembers. “I loved being on the air for the first time in my life.”

In 1969, Halper helped lead the station through a major transition. When she started, WNEU was broadcast only on campus through carrier current, an AM radio transmission that used the dorms’ electrical systems as an antenna. But she helped the station work toward getting a low-power FM license that allowed it to broadcast to the neighborhoods around Northeastern starting in November 1970. Halper was also on the committee that changed the station’s call letters to WRBB. (Trivia quiz: What does WRBB stand for? Radio Back Bay. “We figured that would reflect our new broadcasting areas,” Halper explains.)

Halper is a triple Husky: after getting her bachelor’s degree in the spring of 1969, she stayed for a 1970 master’s degree in college and community counseling (and a few more months at the radio station). She returned for a second master’s, in English, two years later. In between, she worked as a teacher in the Boston Public Schools. She didn’t attend her third commencement, she recalls; she was on the air that day at her new second job as a DJ at WCAS-AM, a folk station in Cambridge.

Her work at WCAS led to her big break, her move to Cleveland. John Gorman, a Boston radio DJ, was hired at Cleveland’s WMMS in July 1973 and tasked with finding new talent and new music. He thought of Halper.

“I used to catch Donna Halper on WCAS,” Gorman recalls. “I thought she handled the format very well. When she introduced a new song or artist that I hadn’t heard before, she set it up very well.” Though he’d never met her, Gorman called Halper and offered her a job at WMMS. She accepted.

“My parents were appalled,” Halper recalls. “They said, ‘You’re going to walk away from tenure in the Boston Public Schools?’ I said, ‘But it’s not where my heart is. My heart’s in radio. I’ve got to follow this. This is my chance.”

New ownership at WMMS had threatened to change the format from album rock if ratings didn’t improve. Gorman asked Halper to discover new music, not just the albums that major record labels were promoting. “And my God, Donna immediately took to the task,” Gorman recalls.

It was Halper’s first time away from Boston, and she recalls not fitting in with WMMS’ hard-partying male staff.

“[For] a woman at the time, 1973, there were glass ceilings,” Gorman says. “She had to fight that much harder for half the role she deserved.” What drove Halper, Gorman says, was “a combination of her knowledge of the music industry, her insecurity, and the fact that she had her marching orders. And she really knew how to do it.”

At Northeastern’s station and at WCAS, Halper had developed a reputation for playing British, German and Canadian imports. So foreign promoters sent new music to her in Cleveland. That’s how it came to be that Bob Roper, a record promoter at A&M Canada, sent her a copy of Rush’s self-titled album after his label had turned it down.

Gorman says Halper’s discovery of Rush helped WMMS succeed. (The station is still on the air, nearly 50 years later.) “The Rush story became a national phenomenon,” Gorman recalls. “It was mentioned in Billboard and all the trades, how this album broke out of Cleveland. Donna finding Rush, and the album breaking out of Cleveland, fulfilled our goal of making WMMS important to the rest of the music industry, in terms of Cleveland being a breakout market.”

Halper’s discovery led to a job in 1975 as a talent scout for Mercury Records in New York City. In 1977, she joined New York jazz station WRVR-FM as music director and afternoon drive DJ. A job at soft-rock station WAVA-FM near Washington, D.C., followed in 1978. In 1979, a job as music director for WHDH-AM in Boston brought her home. “I got to meet Fleetwood Mac, Bob Seger, and Bruce Springsteen,” Halper says. “Bruce Springsteen drank my orange juice.”

But Halper wasn’t on the air at WHDH. So in 1980, feeling that her DJ career had stalled, she reinvented herself as a radio consultant. For most of the 1980s and 1990s, she traveled North America, helping small and medium-sized stations as far away as Canada, Alaska, Hawaii and Puerto Rico with market research, format development, and training for DJs, managers and news directors. “And every now and then I’d get on the air at one of my client stations,” she recalls.

After the Telecommunications Act of 1996 deregulated radio markets, large chains bought up many of Halper’s clients and switched them to cookie-cutter formats. With few clients still giving her work, Halper reinvented herself again. She turned more to part-time teaching at universities in Boston, including Northeastern. Unable to get a full-time professor job, she set out to earn a Ph.D., enrolling at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst’s communications program while teaching there and at Emerson College. After nine years of study, Halper received her Ph.D. in 2011, at age 64.

Hired as a professor at Lesley University in Cambridge in 2008 with the understanding that she’d get her doctorate, Halper has taught communication and media studies there ever since. She’s also written six books, including Invisible Stars: A Social History of Women in American Broadcasting.

“I will always be grateful to Northeastern,” Halper says. Despite the sexism she faced on campus in the 1960s, she says, the university eventually offered her first opportunity in broadcasting.

“You guys got my career started—and yeah, I had to fight for it—but I got there, and it wouldn’t have happened if it weren’t for Northeastern,” Halper says. “I got to take courses and meet people that I never would’ve met. I’m just a working-class kid! What an opportunity for me.”

Erick Trickey is a Northeastern Global News Magazine senior writer. Email him at e.trickey@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @ErickTrickey.