Published on

Behind the scenes at commencement

A year of planning. Hundreds of earpieces. Emergency regalia. Over 9,300 graduates and 46,000 spectators. And lots of thinking about grass. How Northeastern puts on one of the biggest shows in higher ed—then takes it on the road across its global campus network.

It’s 7 a.m on Northeastern University’s commencement Sunday, and Gate B at Fenway Park is already buzzing with activity. Coffees in hand, a fleet of volunteers in red windbreakers and outfitted with earpieces put the final touches on the space before the onslaught of celebrating graduates arrives—4,754 graduate students and 4,643 undergraduates will take the field for separate ceremonies.

It’s just part of the flurry of commencement celebrations taking place across Northeastern’s global campus network. Northeastern University at London kicked things off back in March, with a post-graduate celebration (undergraduate commencement will be held there in the fall). Mills at Northeastern held its ceremony April 30. The Seattle, Vancouver and Bay Area campuses hold their commencements three days apart at the end of May, followed, respectively, by Toronto, Charlotte and the Roux Institute in Portland, Maine, in early June.

This is a show. Over the years, commencement has become more and more spectacular.

Julie Norton, director of academic ceremonies at Northeastern

Today, ballpark concessions will sell 1,964 Fenway Franks to about 46,000 total attendees. Five hundred and nine red fireworks will go off over home plate, and a videographer covering the event will walk 23,999 steps—nearly 11 miles. But there’s a long way to go before then.

Under the stands behind right field, where graduates and faculty will process into the park, team leaders hold meetings to give instructions over the din of the final musical run-throughs. They’re all happening at once: The chorus of Katy Perry’s “Firework,” from the Nor’easters a cappella group, mingles with the pep band’s big brass and the student orchestra’s sweeping woodwinds.

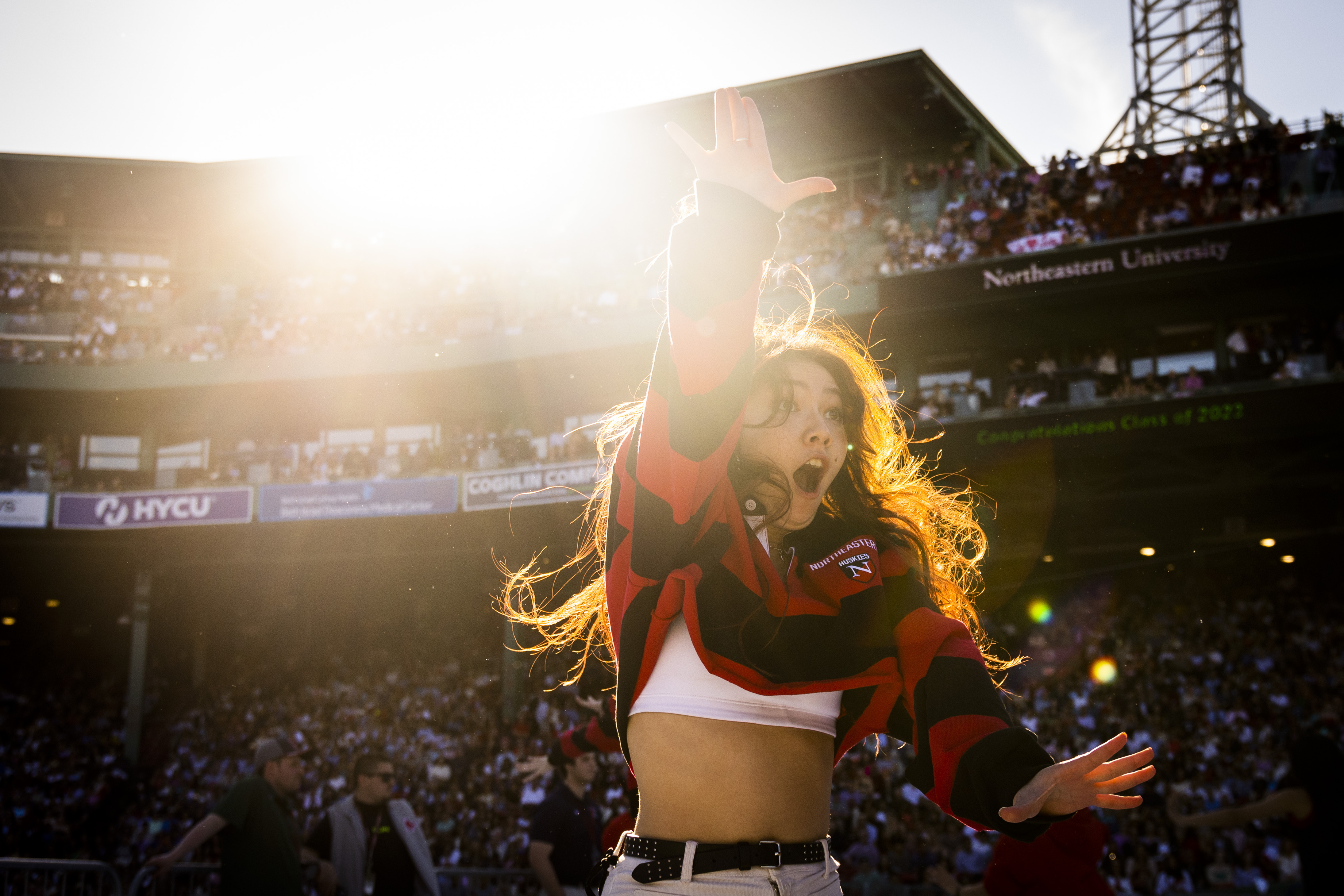

In the outfield tunnel, student dance troupes rehearse their steps one last time before the pre-show. The uniform red dresses and black shoes of Latin ballroom pairs swirl in the foreground, while the hip hop group Kinematix, dressed in an array of red and black athleisure, pop, lock and spin in military unison.

At the mouth of the tunnel, Sebastian Chávez Da Silva, the student emcee, gets ready to introduce the groups. Previously, Chávez Da Silva, the president of Northeastern’s Student Government Association, has emceed for convocation (the beginning of the academic year) and the Light and Joy festival (held on campus during the holiday season). But this is far and away the biggest place where he’s taken the mic. As a Massachusetts native, hearing himself over the sound system at Fenway Park is a thrilling, if daunting prospect—even after four rehearsals and a morning of sound checks. “I’ll try not to stutter,” he jokes.

Wherever you look amid the growing bustle, Julie Norton, Chelsea Kryspin or Lauren Kazi seem to be there. On the field, Kazi, wearing the red windbreaker provided to commencement volunteers, gives instructions in her earpiece while simultaneously shepherding a pair of lost professors to their spots. Norton, dressed in dark jeans, a striped sleeveless shirt, and gold, thick-soled sneakers, a yellow body pack slung over her shoulder, runs back and forth, making sure honorary degree recipients are taken care of and photographers are in position to get shots of the ceremony’s many visual treats.

The trio, who work in the university’s advancement office, have been planning this day for nearly a year. In early June 2022, Norton called the booking office at Fenway Park to zero in on a date—and finally set it in late July, with the release of Major League Baseball’s 2023 schedule. The three women are the point of contact for 360 volunteers from the Northeastern community, supported by the full complement of staff at Fenway Park – about 300 more workers (including ticket takers, vendors, and 100 security personnel).

Global campus commencements

This is toward the start of a veritable road show for the commencement team. In Fenway, they’re joined by staff from across Northeastern’s 14 campuses: Suzi Broadaway, the head of student life at Northeastern University in London, flew in this past Saturday. “I’m doing anything that needs to be done,” she says.

Also on hand is Anne Maria Jacobson, associate director of academic ceremonies. Based at the Seattle campus, Jacobson coordinates the commencements still to come, with assists from members of the Boston team. At Fenway, she is responsible for organizing the platform party—making sure names are on the assigned seats, the podium is set up properly, and that those onstage have plenty of water and sunscreen. In the afternoon, she’s tasked with watching the undergraduate ceremony closely. “They break me free so I can focus and really study what the students are responding to, and see how I can I weave that into the global ceremonies.” she says.

“This is a show,” says Norton in an interview a few days before the Fenway celebration. “Over the years, commencement has become more and more spectacular.” That’s true across the campus network, which has grown so much that the commencement team has had to seek out new, larger spaces to celebrate graduates. With the exception of Mills (which held its ceremony on campus) and Boston, every commencement is at a new venue for 2023.

“The majority are in theaters or performing arts centers that should lend themselves well to the experience and give us the support to pull it off,” Jacobson says. She strives for a “wow” factor in those spaces, too: The Bay Area ceremony is in the historic Fox Theatre, a lavishly renovated Art Deco building in Redwood City, California. Seattle graduates will walk across the stage of the Benaroya Hall, home of the Seattle Symphony. Toronto will graduate the largest of global network cohorts in Roy Thomson Hall, a vast and storied performing arts space.

Those spaces range in size and character as much as their graduating classes, with the largest being 650 in Toronto. So Jacobson and her team look for opportunities to both telegraph unity across campuses and lend consistency to their planning. “We try to come up with design elements that are really simplistic, like colors and lighting cues, so we don’t have to build something,” she says. Like touring acts in concert halls, commencements need to be loaded in and out on the day; there’s no time for full rehearsals. Another important consideration is choosing spots well-equipped for televised or recorded events. “Livestreaming becomes essential because we have a very strong international community in the global network, and many families cannot fly in for this,” Jacobson says.

Back at Fenway Park

At Fenway, of course, the team has a vast recording and live event infrastructure at its disposal; at times, the possibility of the historic ballpark seems endless. “We’ve probably talked about a hundred different interesting things we could do — and many things Fenway said we couldn’t do,” Norton says. “Drones, fly space.”

“Can’t do drones,” Kryspin agrees.

Kazi has worked on commencement since 2019, when the ceremony was held indoors at TD Garden. The move to Fenway, she says, comes with big advantages and fresh sources of anxiety. “In TD, we were very cramped. It was maxed out, and students could only bring three or four guests,” she remembers. Graduates no longer go onstage for their diplomas, which means there’s no assigned seating and they can sit with their friends. At TD, graduate seating bled into the stands, making entering and exiting a lot more chaotic.

However: grass. “We know more about grass than we ever wanted to,” Norton laughs. The team has to take all possible measures to protect the ballpark’s field, composed of a proprietary blend of Kentucky bluegrass sod shipped up from New Jersey. “We pay for this very expensive white floor covering. They put it down in the evening so it doesn’t capture heat, and it’s down for 24 hours,” Norton says. Flowers are banned, so the seeds don’t germinate in the grass. Aside from water, in fact, most things are banned. “Diet Coke can ruin grass — everything!” Norton says.

With Fenway, too, they spend months fretting about the weather. Short of a cataclysmic meteorological event, commencement has to happen on the appointed date—there’s no backup plan for rain. Last year, the heat, which climbed into the 80s, became a safety concern.

Today is gorgeous and clear, with a hint of a breeze, but already quite warm by mid-morning. Huge coolers on wheels, filled with ice and bottled water, stand at the ready. Fenway staff will wheel them out intermittently throughout the ceremony for the graduates, sitting in direct sunlight. The special plastic flooring and stage are in place—the latter put up less than an hour ago.

In the sunny corridor between Fenway’s box seats and right-field bleachers, Chris Bosso, a longtime professor of public policy at Northeastern, stands in a black robe, holding Northeastern’s ceremonial mace. This is Bosso’s second year as the head of the cadre of faculty marshals who lead graduates onto the Fenway field. With the temperature climbing toward 78 degrees, is it hot in that robe? “Not as hot as wearing the husky outfit,” Bosso says—in solidarity with Paws, the mascot, who’s prowling the field.

Before the ceremonies begin

Before the ceremony, Bosso is in charge of organizing the faculty marshals’ logistics. During the ceremony, he’ll be the first on stage. Wearing a black cap with a golden tassel, and a blue Ph.D. hood over his shoulders, he’ll ascend the stage carrying the ceremonial metal mace, an ornamental staff about 2½ feet long and weighing about 10 pounds. It’s crowned with Northeastern’s seal, in gold, and a silver eagle, wings arched.

“You don’t want to be on the receiving end if I swing that sucker,” Bosso says. “It’s good for crowd control.” He’s kidding, but his ancient predecessors weren’t. Ceremonial maces, he explains, date back to British royal and parliamentary custom; a mace in the House of Commons meant the house was in session. “They were for crowd control as much as anything else, back in the rowdy days of the old legislatures.”

Once he’s onstage, “the stressful part for me is pretty much over, because as long as I don’t trip with the mace, I’m good,” Bosso says. “If things go well, we’re ornamental.” Despite the crowd, he has no stage fright. “Like any faculty member who’s given lectures to a few hundred students, you don’t even think about it, because it becomes an abstraction. There’s the first three rows, and beyond that, it’s just people.”

Meanwhile, more faculty are getting ready in the State Street Pavilion, below the press box. Audrey Ring, a senior associate in the development office, and her team are outfitting a few dozen professors with regalia (which Kazi set up and organized ahead of time). “I don’t get to chat with faculty all that often, so it’s nice to get some face time with them,” says Ring, who’s heading up the robing team for the second year. Her job isn’t over when they’re all dressed and sent to their posts—in the chaotic lead up to the procession, she makes the byzantine walk from the pavilion to Gate B several times, shepherding straggling faculty.

At the same time, the leaders of the field team—Matt Harrington, Mike Sampson,and Eric Hatch—are poised to wrangle the crush of graduates as they take the field. It’s one of the biggest jobs of the day, requiring over 70 volunteers. “It’s almost like being in the trenches, in the happiest way,” says Harrington, an assistant director of campus and community events.

That means they’re on the front lines for any problems the students might have—serious or otherwise. That can include physical issues, like dehydration. “Last year, it was 80-plus degrees,” says Sampson, an associate director of fraternity and sorority life on the Boston campus, “and we pivoted very quickly to passing out water to students on the field.”

Lost and found

Another contingency: extra bags, tassels, mortarboards, and cords. “There’s always a huge group of graduates who arrive with missing regalia,” Harrington chuckles. “Sometimes it’s weird what they’re missing. Luckily, we have a ton of extras at their disposal. Whatever college they’re from, we can figure it out within seconds.” He points to a table in front of a closed concession stand, groaning with heavy yet immaculately organized cardboard boxes. In the minutes before the procession starts, Sampson weaves purposefully through the throng, his arms fringed with a veritable rainbow of spare tassels.

In the trenches, as it were, the three men are acutely aware of what a milestone this is for graduates—and the range of responses that can accompany that. “One thing I always try to help volunteers look out for is, you’re going to get a wide variety of emotions that come out that day,” Sampson says. “I always say, keep a pulse check on where they’re at. Is someone visibly upset? Excited? Sad a family member couldn’t make it? Do we need to provide support there in some way?”

“Some students get what looks like stage fright,” adds Hatch, who works in the registrar’s office. “The whole spectacle of the thing makes them go deer in the headlights.”

They’re grateful for the order of the day, corralling the smaller, more businesslike cohort of graduate students before the rowdier, young undergrads in the afternoon. “That’s party city,” Harrington says. “And the sheer amount of confusion increases so much.”

The moment of truth

As the moment of truth for the field team arrives, and students begin to file to their seats, Shams Ahmed is taking one final break in Fenway’s right field concourse. He stands out in the black-robed, tightly-packed mass around him: He’s dressed in light colors, including a well-worn khaki vest with roomy pockets, white Gucci-branded high top sneakers, and circular white-rimmed sunglasses. He relaxes down on a set of stairs while an assistant fetches him a bottle of water. If it weren’t for the surrounding urgency, and the fact that he’s about to perform arguably the most precise, high-pressure duty in a day replete with them, he would seem to have plenty of space and time to chat.

Ahmed is the creative director and producer for the pre-show entertainment and the ceremony’s grand finale—an exhilarating, seven-minute musical extravaganza in which student dancers flood the field and the aisles, student poet Chinma Nnadozie-Okananwa reads an original work, and the Nor’easters join with the pep band for a rousing rendition of “Firework.” He’ll be locked in, calling every music and mic cue, monitoring sound levels, and making adjustments on the fly. “Do not even look in my direction,” during the finale, he jokes.

Ahmed graduated from Northeastern in 2013 with a finance degree and was an active member of the Nor’easters, directing and arranging music for the group. He now works with a cappella groups professionally as an arranger and coach, and he’s produced a bevy of large-scale events for the university. In ensuring the finale goes off smoothly, he says, the biggest technical obstacle is the sheer size of Fenway Park.

“Because sound travels much more slowly than light, you have to account for a ton of what we call ‘slapback,’ ” Ahmed explains. “Something that’s happening two inches away from you is going to sound a certain way.” But across the ballpark, “there will be a lot more of a delay in what you’re hearing.”

The performers and music conductors, too, are far enough apart that they can’t rely on each other to stay together. Instead, they have a click track played through earpieces to keep everything on time. “They’re not actually listening to what’s happening in the house. They’re listening to what’s happening in their ears,” he says.

For most of the “speeches” portion of the ceremony, Ahmed perches in a thin patch of shade next to the sound booth, which is under a small white tent at the very back edge of the white floor covering. As the deans of the eight Northeastern colleges take the podium to confer degrees, he steps to the front of the booth, a printed sheet of time cues in one hand and a black microphone in the other. “Cue finale,” he says, as the Nor’easters kick off the finale with a few bars of hymn-like harmony. The show springs to life as he murmurs, barely audible, into the microphone. Dance team members swarm from all sides. One line of smiling dancers faces the booth, and Ahmed sings and shakes his hips along with them, yelling encouragement and clapping along.

As the final bars of “Firework” break into a swell of applause, he releases his shoulders and pumps his fist. But not too hard. This was the morning graduate student ceremony; Ahmed—and everyone else—will do it all over again in the afternoon. The undergrads start arriving in about an hour.

“One down,” he quips.

Northeastern Global News Magazine senior writer Erick Trickey contributed reporting.

Schuyler Velasco is a Northeastern Global News Magazine reporter. Email her at s.velasco@northeastern.edu. Follow her on Twitter @Schuyler_V.