Published on

Far from home, dream now reality

When John Lenard Rivera was 11, a typhoon destroyed his family’s home in the Philippines. So they moved to Tondo, a poverty-stricken neighborhood of Manila. There, he saw people dying in the streets. But Rivera’s circumstances didn’t stop his ambition. He set his sights on earning a scholarship to attend Northeastern. At Sunday’s commencement, Rivera will receive his bachelor’s degree in civil engineering.

When John Lenard Rivera was 11, a typhoon destroyed his family’s home in the Philippines. So his family moved from Rizal, a province outside the capital, to a small home in Tondo, a poverty-stricken, overcrowded neighborhood of the capital, Manila.

“I saw people dying in the streets of Tondo, especially because of the war on drugs,” Rivera says.

Since the authoritarian former President Rodrigo Duterte took office in 2016, Tondo has been ground zero for police violence against suspected drug dealers, drug users and even loiterers; critics have called it repression of Manila’s poor. Rivera says he’s seen people shot and bleeding, and he’s feared becoming a victim of the violence.

“I felt more scared every time I went out, especially at night, because you didn’t know if you’re going to be a target,” Rivera says. “So I’d just go from school to the church and then straight to the house. At night, you don’t really stay outside.”

Rivera’s circumstances didn’t stop his ambition. He kept telling his parents he wanted to go to college abroad. “I want to experience what’s happening outside of the Philippines, so I can bring something back,” he recalls telling them.

Since eighth grade, Rivera has wanted to be an engineer. At his high school, he was elected student government president three times, was his class valedictorian, and received two Philippine government medals for academic excellence.

Rivera set his sights on the ICTSI-Northeastern University Scholarship Program, which awards a full scholarship to one Filipino student a year to attend Northeastern University. After several screenings, interviews and exams, he received the scholarship.

This week, Rivera receives his Northeastern bachelor’s degree in civil engineering at commencement. Throughout his five years as a Northeastern student, and during his co-ops in Manila and Boston, he’s often given back to his community in Tondo, and to his mother, who’s in her mid-60s and has been slowed down by a stroke.

“I always try to remember where I came from,” Rivera says, “and teach my friends and the people from the Philippines what’s here, so that they can dream big too.”

When Rivera arrived at Northeastern in fall 2018, the normally confident student kept to himself at first, or socialized with other Filipino students. “I was really scared to talk to non-Filipinos when I was a freshman,” he recalls. His native language is Tagalog; in high school, classmates who had better English skills made fun of him. But his freshman year roommate, Mohammed Tanner, a student from Syria, encouraged Rivera to speak English all the time, to build his language skills.

“As an immigrant myself,” Tanner says now, “and someone who had to [acclimate] to a new environment, I did advise him, ‘You have to learn regardless. So stick with it. Make sure that you’re practicing English.’ But his English was actually not bad at all.”

Dancing helped Rivera break out of his shell. He’s danced since he was 10, when he stood outside a neighbor’s house in Rizal, watching a dance team practice every night. “Just by watching them, I learned the whole set,” Rivera recalls. “Then they saw me dancing.” Impressed, the dance team trained Rivera, started a kids’ group and put on shows with him. Rivera danced in high school and competed in dance competitions in Tondo.

So, as a freshman, Rivera joined Kinematix, Northeastern’s hip-hop dance troupe.

“He’s always there to brighten up people’s moods; he’s the energy maker,” says Julia Mei, a former president of Kinematix who was a “newbie” with Rivera in 2018. “Whenever he feels like the energy is down, he’s the one who says, ‘Come on! We got this, guys! Let’s push!’”

In 2019, on a trip to New York City, friends from Barkada, the Filipino club at Northeastern, shot video of Rivera dancing to the Filipino pop hit “Bagay Tayo” by the hip-hop group ALLMO$T. Watching the video, it’s hard to imagine the shy side of the twisting, shimmying, smiling performer, throwing his arms wide in a public park.

Rivera, who danced in high school and competed in dance competitions in Tondo, performs hip-hop and modern dance with Kinematix. “We always try to have a diversity in our moves and our choreographies and the texture of our bodies whenever we dance,” he says. He especially enjoys dancing to “Get It Poppin’,” the 2005 hip-hop hit by Fat Joe and Nelly.

COVID-19 interrupted Rivera’s time in Boston. Back in Manila, coming home from the airport, he saw the capital’s streets nearly empty. “I saw the homeless people and I thought, how are they going to get food if everything’s going to be closed? No one’s going to give them food because no one can really go outside.”

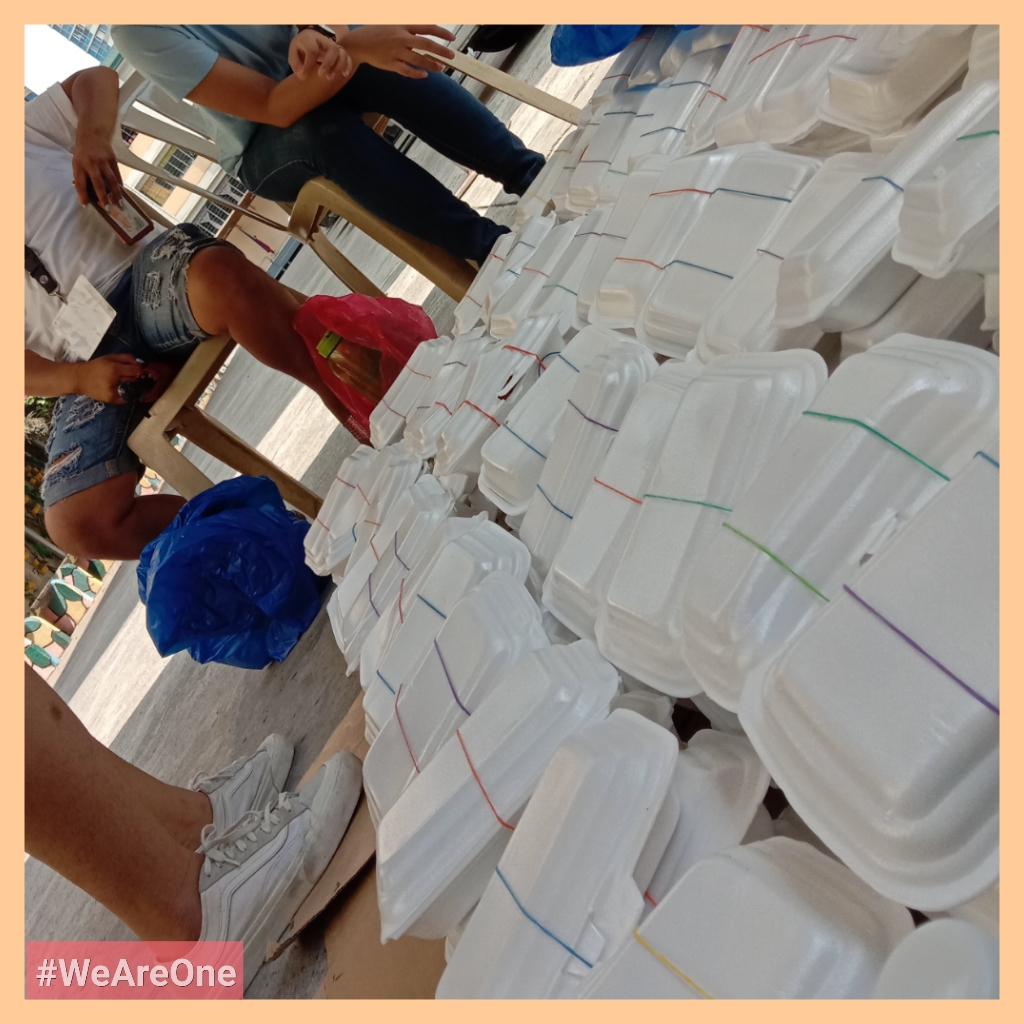

So in April 2020, Rivera, who had volunteered for his church’s food program as a teen, organized some of his old high school classmates into a charity group they called We Are One. They set up a Facebook page and emailed people, including Rivera’s Northeastern friends, asking for donations. They raised about $3,000 to buy food. Rivera hired some of his relatives, who had a small business selling breakfast food before COVID-19, to cook 200 meals. After getting permits to go outside during quarantine, We Are One volunteers packaged the food, then fanned out around Tondo to give it away.

While home in Manila, Rivera also started his first co-op, with International Container Terminal Services Inc., the company that sponsors his scholarship. With his boss stuck in Malaysia, Rivera represented ICTSI, a billion-dollar, Philippines-based global port manager, in its day-to-day work with contractors on an expansion of Manila’s shipping-container port.

“That was my first time seeing an actual engineering [project],” Rivera recalls. “So every time there was a problem on site, I always called my manager. But he really gave me a lot of freedom to learn.”

Rivera didn’t just talk to the workers and managers at the port. He wanted to try the construction work himself, to briefly know what he was overseeing. It was an unusual request. The construction workers, in T-shirts and vests, looked skeptically at the young assistant manager in his uniform: a polo-style shirt, slacks and loafers.

“Are you sure you want to do this?” he recalls them asking. “Yeah, I really want to experience how to do it,” he replied. So they handed him the welding torch, and he learned how to install rebar, to reinforce the concrete that was extending the port farther into the sea.

With his new salary, Rivera began helping students at his former high school buy books and school supplies. “I’m not used to having a lot of money,” he says. “Every time there’s someone who needs help, I just give what I can.”

Rivera also helped his mother, who is widowed and suffered a mild stroke in 2018 that restricts her movements. He renovated her tiny home—only 100 square feet. He drew up designs, built tables, installed cabinets, and bought new appliances, including an air conditioner. He paid a neighbor to help him with the work, and did the rest himself, for a total cost of $1,000.

Once back in Boston in spring 2022, Rivera did a second co-op, with the Boston Water and Sewer Commission. Officially, it was a design co-op, reviewing drawings. “But I don’t really like staying inside,” Rivera says. He asked his boss to send him out in the field. He spent most of his internship as a surveyor, driving around Boston and measuring the layout of areas where the city would do water and sewer work.

Rivera spent some of his pay from that job, too, to help his mother, who had told him her vision was clouding up. He sent her money from his first paycheck for a checkup, which revealed cataracts, and then paid $1,200 for her cataract surgery.

When Tanner and Rivera reunited on campus post-COVID, “there was a lot of growth in how confident he is,” says Tanner. “He knows how to have a good time. He breaks into song and dance. People like to be around him.”

During his senior year, Rivera has worked as a presidential ambassador, staffing campus events. He’s preparing to take the exam to become an engineer in training. Though he’s walking in May’s commencement, he’ll earn his final Northeastern credits this summer in Argentina, learning Spanish on a Dialogue of Civilizations program. His former boss from Boston Water and Sewer, now at a private engineering company, has given him an informal job offer. He plans to spend three to five years working in the United States, getting the necessary experience to take the second exam to become a professional civil engineer.

“I want to save money, and then go back to the Philippines and make my own engineering company,” Rivera says. Some port construction workers he met at his first co-op told him they want to work for him. Neighbors in Tondo who work in construction do too. “So I feel like I already have a team in the Philippines,” he says.

Rivera is still dancing, both with Kinematix and with the INC Boston Dance Crew, made up of working-age adults and some college students. “I still want to dance after graduation while working here,” he says.

His mother, in Manila, is Kinematix’s number-one fan. She’s often the first to like and comment on the troupe’s latest Facebook post. “She’s really proud of what I’ve been doing, and she’s very, very supportive,” Rivera says.

“She told me to enjoy this, because a lot of people applied for this scholarship. She keeps on reminding me where I came from, every time I talk to her.” She wants him to come home, at least once he’s got his professional license.

“I always think of what’s happening in the Philippines,” Rivera says. He laughs nervously. His eyes tear up. “Every time I eat, I always think there’s a kid in the Philippines who can’t eat. So that’s why I want to work and help anyone from the Philippines, anyone from Tondo.”

Erick Trickey is a Northeastern Global News Magazine senior writer. Email him at

e.trickey@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @ErickTrickey.