Published on

Rock star interviews, ‘raw,

complete and unedited’

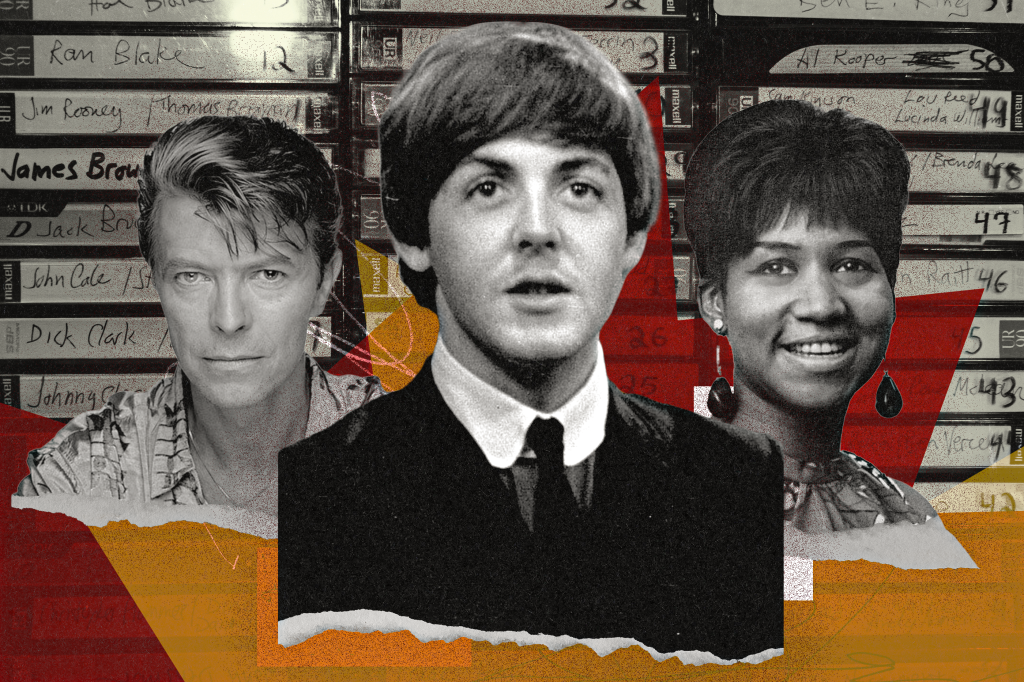

Aretha Franklin, James Brown, Miles Davis, Lou Reed, Paul McCartney and Yoko Ono all spoke to Larry Katz during his music journalism career, and all of their interviews are now a part of Northeastern Library’s digital archive known as the Katz Tapes

Larry Katz remembers the time he met Prince backstage after a show.

It was March 17, 1981, and the musician had just performed a full set at the Boston Metro, the sixth stop of the second leg of his Dirty Mind Tour. Katz remembers the “mind-boggling guitar solos,” and that, by the end of the show, Prince was wearing next to nothing.

But when Katz met Prince as he lounged in a sound booth after the gig, it was like he was talking to a different person entirely. For one thing, he was wearing a bathrobe (Prince, not Katz); for another, Katz remembers him as “quiet and shy.” In the audio of another recorded interview between Katz and Prince, the singer can barely be heard.

Katz, a newbie music journalist, taped his first interaction with the singer, and wrote an article about the show for the now-defunct alternative newspaper The Real Paper. When he retired 30 years later, he brought the cassette home and put it in a box with nearly a thousand others like it. There it sat, gathering dust.

That is, until Katz decided he needed to do “something” with them before they started to deteriorate.

Now, for the first time, Katz’s interviews with some of the most famous musicians and other cultural figures in history—many of them now deceased—are available for the public to peruse. Aretha Franklin, James Brown, Miles Davis, Lou Reed, Paul McCartney and Yoko Ono all spoke to Katz during his career, and all of their interviews are now a part of Northeastern University Library’s digital archive of what’s known as the Katz Tapes.

The archive is the result of years of work sorting through hundreds of hours of interviews. According to Giordana Mecagni, Northeastern’s head of special collections, some interviews were split over multiple tapes; sometimes, more than one interview was on one tape. After Katz decided to donate the collection to Northeastern University Library in 2020, she says, the library’s digital production team listened to every second. They identified the speakers, and pieced the interviews together and stored them in a browsable archive.

The result is a raw, complete and unedited archive, something Dan Cohen, dean of libraries at Northeastern, says is incredibly rare. Archives are usually curated in some way, or parts are missing. These tapes, meanwhile, are long—Katz estimates that he used about 25% of the material in his articles for the Herald—and capture everything, from the everyday to the outlandish. Katz catches artists, usually over the phone, in an itinerant state, in the middle of a tour, living out of a suitcase in a hotel room, or, as Cohen puts it, “midstream.”

Indeed, one thing Cohen noticed when listening to the tapes is not the speakers themselves, but the noises they make. A phone rings, a musician coughs or takes a bite off their plate. People walk in and out of the room as Katz chats with Bob Marley. Technological challenges—Katz used an old mechanism for recording phone interviews, with varied results—make some of the recordings staticky. Some are nearly indecipherable.

Katz, for his part, takes pride in his role as someone who was able to create this unfiltered material. “I always looked at myself as a conduit for the people I was talking to,” he says. “I wasn’t looking to insert myself in there; I was looking to convey the truth of what the person had to say.”

But Cohen implies that, actually, he hears a lot of Katz in the tapes. Each tape is a look at the artist, but it also provides a window into a music journalist at work, he says. A former musician himself, Katz did his homework, going to the library and reading on his subjects to prepare for interviews. He worked hard, he says, to develop rapport as a professional whom the artists could trust not to sensationalize them.

Then, of course, there’s his ability to put people at ease, to allow them to open up and maybe even shed some of that rock star persona. “However you can create empathy, you try to do so,” he says. Artists would talk to him, and, Katz says, that means you might hear some Easter eggs.

“My concern was there might be stuff in the tapes that was off the record or revealed some personal information that maybe the person wouldn’t want out there,” he says.

He has no idea if that’s the case. It was Katz’s policy to turn off the tape recorder when someone wanted to go off the record. “Did I turn off the tape recorder 100% of the time? Maybe not, I don’t remember,” he says. “Who knows what’s in there.” (Singer Jimmy Merchant’s home address, for one.)

Now retired and focused on being a grandfather, Katz is working on adding blog posts to the website to help provide context and personal reflections for the interviews. He hopes the tapes will be of public use. Cohen certainly thinks they will be—as he points out, the tapes provide a window into the history of the music industry, as well as the country as a whole, over the course of a quarter century.

The tapes do something else, too: they bring the ones who have left us back from the dead.

“If you listen to the tape, there they are; they’re alive again,” Katz says. “And that’s kind of a wonderful thing.”

Katz amassed nearly 1,000 tapes of interviews over a 30-year career. The full collection is housed at the Northeastern University Library. Here are some of his favorites:

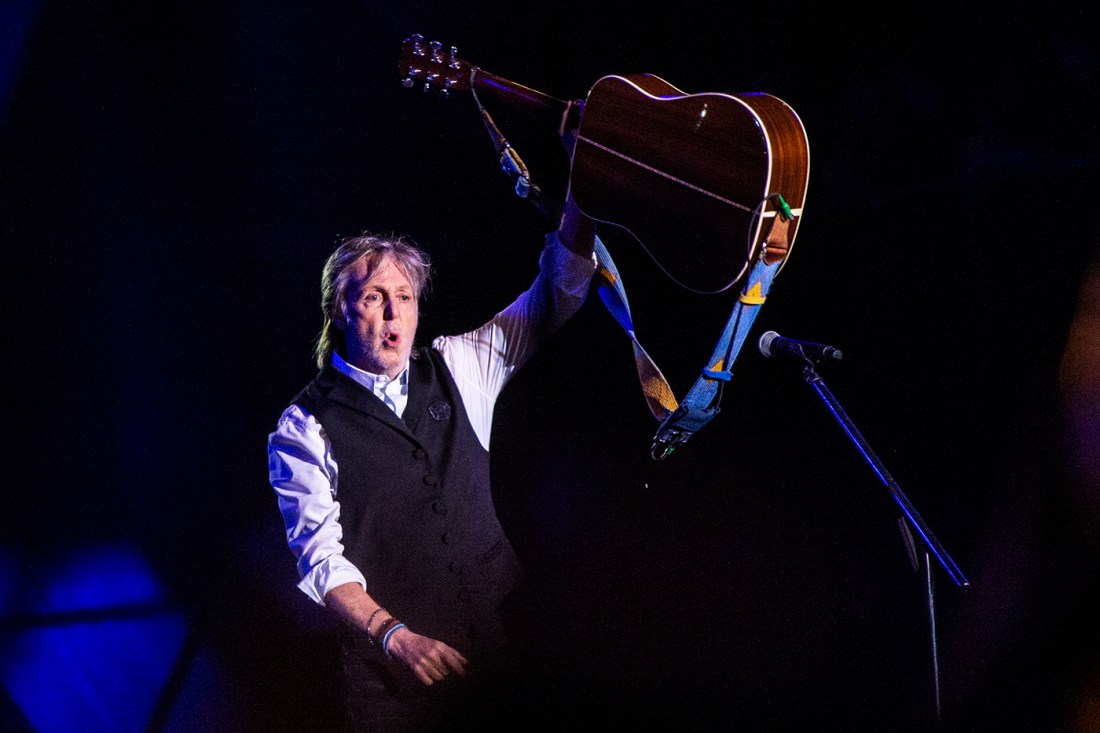

Paul McCartney moves on from loss

For the first few minutes of his 2002 interview with Paul McCartney, Katz sits in silence. Paul is late.

When the former Beatle finally shows up, he’s in good spirits.

“We’re having a great time,” he says.

It would seem like a strange way for McCartney to start an interview, at least at the time. Just a few months prior, McCartney and his band had watched from their parked plane as the Twin Towers fell; a national mourning period was ongoing.

On top of that, McCartney had just faced two of the biggest personal losses of his life—the death of his wife of 30 years, Linda, to cancer in 1998, and the death of Beatles bandmate George Harrison in November 2001.

McCartney, who was in Boston in the middle of his Driving World Tour, speaks openly about both losses, saying of Linda, “We just expected to carry on and grow old together, but that wasn’t to be.” With regards to Harrison, “I miss him a lot,” McCartney says.

But for the most part, in his interview with Katz, he isn’t raw with grief; instead, he’s hopeful, having emerged from what he describes as a “tunnel of sadness.” “I’ve been able to get over the sadness or some of the sadness of losing Linda,” he says. “I’m entering into a new, much happier period in my life.”

The Driving World Tour would be his first since his wife’s death. That meant he had to dust off his old records, listen to his own music, and relearn how to play songs he had written decades ago. People assume he’d remember how to play his own songs, he says. He doesn’t.

He isn’t one of those musicians who need to keep things fresh, either. He’ll play the old stuff, and he’ll play it as he always has. “I’m a bit of a believer that audiences in the main like to hear things as they know them,” he says. “I change them a little bit occasionally, but not mainly. Mainly I stick to the arrangement.”

The McCartney we hear from in this tape has taken a beating, but he’s come out the other side with new music, some hope, and fresh wisdom.

“I think the only regret in life is you don’t get to know people as much as you want to,” he says. “And that shows up when you lose them.”

Aretha Franklin keeps her cards close to her chest

Katz’s voice takes precedence in his staticky recording of a 1991 interview with Aretha Franklin.

On tape, Franklin is forthright but guarded, answering questions in clipped responses that don’t invite further conversation, something Katz says she was known for.

“She was very self protective with everyone who ever interviewed her it seems, not just me,” he says. “I worked hard to get her to loosen up and she never did,” he wrote in his blog.

At the time of the interview, Franklin was preparing to go on a bus tour to promote her album “What You See is What You Sweat,” which ultimately flopped. Traveling with a 17-piece orchestra, Franklin planned to perform her new material as well as the hits that made her legendary.

But the conversation doesn’t flow. Instead, Katz moves from question to question as if reading from a list. When she finishes a sentence, he sits silently to give her space to say more, but she rarely does. A phone rings in the background, and thunderstorms are raging in Katz’s Boston office.

“Every time it rains, it blows all my TVs out,” says Franklin.

But talking about the weather with Aretha Franklin is still talking with Aretha Franklin. Here, we get snippets of who the singer was behind the scenes: she crocheted, cooked, and golfed, but only on driving ranges. She loved all kinds of music, including the new stuff (“I’m a contemporary lady,” she says). And she loved Detroit.

“We’re very metropolitan,” she says, correcting Katz’s assessment that it isn’t much of a tourist destination. “I think you just have to know the best and finest places to go to.” She calls the Renaissance Center the “ninth wonder of the world.”

She doesn’t seem too disappointed that the Detroit Pistons didn’t make it to the championships that year, though. Instead, she lights up over Michael Jordan. “I really wanted to see Michael Jordan get that ring this year, because the Pistons, they’re great players, they’re great guys, but they already have two rings,” she says. “Michael has worked so hard.”

When Katz asks Franklin to name someone she admires musically, she doesn’t give him anything. She does ask him a favor, though: when he brings up that time she played on TV with Levi Stubbs, she asks him to send her a copy of his tape.

Katz says he’ll get the tape to her through her agent. While his memory is fuzzy, he’s pretty sure he never did.

Stevie Nicks goes it alone

Stevie Nicks was at her house in Los Angeles getting ready to go to rehearsal, her hair done up in braids, when she got a call from Larry Katz.

The year was 1994, and Nicks was about to kick off a tour to promote her solo album “Street Angel.” It wasn’t the first time she would be performing solo, she explains, but it would be the first time she was performing solo after her well-publicized split with Fleetwood Mac.

Now on her own, the guilt of having to split her time between the two endeavors was gone, she tells Katz. And, she had the opportunity to move forward with her life.

“This is the first time that I’ve ever gotten to completely concentrate on my show,” she says, “and really put my whole heart into it. It is kind of like when you get a divorce, and the divorce is final, then you have to go on with your life. You have to. And going on with your life is really good, it’s amazing. It’s an amazing feeling.”

Nicks was a seminal talent as one of the lead singers of Fleetwood Mac. It started, she says, when she got a guitar on her 16th birthday. Before she was ready, she was in a band with guitarist Lindsey Buckingham opening for acts like Janis Joplin at the Santa Clara Fairgrounds in front of 75,000 people.

“I didn’t have any preparation for that,” she says. “It was the most frightening moment of my entire life.”

It did prepare her for the superstardom that came with headlining one of the biggest bands of the 70s, and the attention that she refers to as “that whole machinery.” Unfortunately, that meant giving up parts of herself for the sake of the band. Having children, for one thing, was set aside, something she regrets.

“It was just never the right time,” she says. “It was never that I didn’t want to have them. It was that everybody else around me, [their] life would be completely screwed up.”

She tells Katz all this as if she’s talking to an old friend, or, perhaps, as someone who’s used to keeping parts of herself secret. On stage, “There is this kind of being that I turn into,” she says, someone ethereal, mystical. There’s another part of her, she says, who’s down to earth.

“Somewhere between the two, I guess, is me. The real me.”

David Bowie chooses chaos

“Good morning, it’s David Bowie calling.”

When David Bowie called Larry Katz, he was sitting in a hotel room in Hartford, Connecticut. It was the early hours of Sept. 14, 1995, and the glam rock star was about to embark on a 99-show, three-leg, worldwide tour to promote his latest album, “Outside.”

Katz catches Bowie, then, in the calm just before the storm.

If Bowie is anxious about what’s to come, he certainly doesn’t show it. Instead, he speaks clearly and carefully, telling Katz how much he likes the art museum in Hartford, how he’s creating a series of paintings of everyone on tour with him, and how extreme performance art came to inspire his latest album, for which he collaborated with Brian Eno.

Bowie’s calmness, his sheer normalcy when talking to Katz, can be seen as irrational as the potential for a disastrous tour looms. Bowie won’t play his old hits on the new tour, saying “they’re too worn for me,” but will start touring before “Outside” is even released. And as Katz notes, Bowie is touring with Nine Inch Nails, a strange choice considering their contrasting musical styles. At the time, Katz notes, some were saying that concert goers would walk out once Nine Inch Nails finished their set and Bowie made his appearance.

“That’s extremely likely, isn’t it?” Bowie replies. He embraces the opportunity to perform with Trent Reznor, he says, with whom he would share the stage for about 20 minutes. In fact, Bowie had personally asked Reznor to join him on the tour. “At one point we have both bands playing.”

Bowie doesn’t need certainty, he says, and actually, he thrives on chaos. “It’s what I have to do to maintain my momentum as an artist,” he says. “I have to put myself in rather adventurous or hazardous situations.” He says letting go of others’ expectations is essential for creativity.

Becoming comfortable with chaos transcends the art world; he calls absolutism “almost an anachronism in this particular era,” and something that breeds intolerance. “I think the idea of becoming comfortable with the idea of chaos is how we are progressing,” he says, “that life and the universe is extremely untidy.”

In short, Bowie knows he’s taking a risk on this tour. He just doesn’t seem to care.

“I don’t really want a safety net,” he says. “That produces nothing.”

Bob Marley nears the end

When Katz interviewed Bob Marley, it was at the beginning of his career.

Sadly, it was at the end of Marley’s. Just days after Katz interviewed the reggae legend in advance of his performance at Hynes Auditorium in Boston in September 1980, Marley would collapse in New York due to melanoma that had spread to his brain.

But when Katz talked to Marley, he would have no way of knowing he was speaking to a dying man. In fact, what stuck with Katz most following the interview was Marley’s laugh, which Katz described as “high-pitched and boyish, the innocent laugh of a child who knows only happiness.”

Katz did understand the privilege he had been given. Katz had only been writing for nine months, and was enraptured by Marley, whom he calls “one of my heroes.” As Marley lounged in a hotel room chair, other journalists gathered and sat on the floor around him like a kindergarten class.

What they heard was a disjointed and at times nonsensical conversation. Katz jumps from topic to topic, and the self-assured Marley abides. He jokes that he has “a few” children (he had at least 10). He says he isn’t interested in playing solo (“It’s good to have community. It’s the greatest feeling,” Marley says). He says he had only taken up guitar eight years prior, and played soccer to build up stamina for shows. He doesn’t support anyone in the upcoming Jamaican election, because none of the candidates are Rasta.

When asked what kind of music he likes, Marley says he listens to everything. “You see, the ears is never tired of hearing nor the eyes tired of seeing,” he says.

As cameras click in the background, Katz asks one of the more mundane questions of the interview: do Marley’s children go to school?

Of course, Marley says. “School is important,” for teaching children things like math and history. At the same time, “They know the truth already,” he says. “There’s only one thing can corrupt them—when you don’t know God.”

Marley died in May 1981 at age 36.

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.