Published on

Israel-Hamas war: Is the two-state solution dead?

The long-sought idea has been for Israelis and Palestinians to negotiate a settlement providing each with its own independent state. Faculty experts from Northeastern’s Jewish Studies and International Security Studies programs and School of Public Policy weigh in.

This report is part of ongoing coverage of the Israel-Hamas war. Visit our dedicated page for more on this topic.

For the longest time Lori Lefkovitz believed in the promise of a two-state solution that would resolve tensions between Israelis and Palestinians.

“Under the immediate circumstances it feels wrong and untimely even thinking about it,” says Lefkovitz, the Ruderman Professor of Jewish Studies and director of Jewish Studies at Northeastern University.

More than 1,300 Israelis have died in the shocking Oct. 7 attacks by Hamas, the militant group that rules the Palestinian territory of Gaza, a 25-mile slip of land whose airspace and shoreline are controlled by Israel.

Israel subsequently declared war on Hamas with the vow of “crushing” the terrorist organization. Airstrikes have left hundreds of thousands homeless in Gaza.

Max Abrahms, a Northeastern associate professor of political science who is an expert in international security and terrorism, says the odds are extremely small of negotiating peace between Israelis and Palestinians.

“There are some problems where it’s very difficult in practical terms to come up with a solution, and I believe the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is an example,” Abrahms says. “It’s like someone looking at a terminal case of cancer. They want to solve it. But not all problems are solvable.”

Lefkovitz and Dan Urman, director of the law and public policy minor at Northeastern, hold out hope for a peaceful settlement between Israelis and Palestinians.

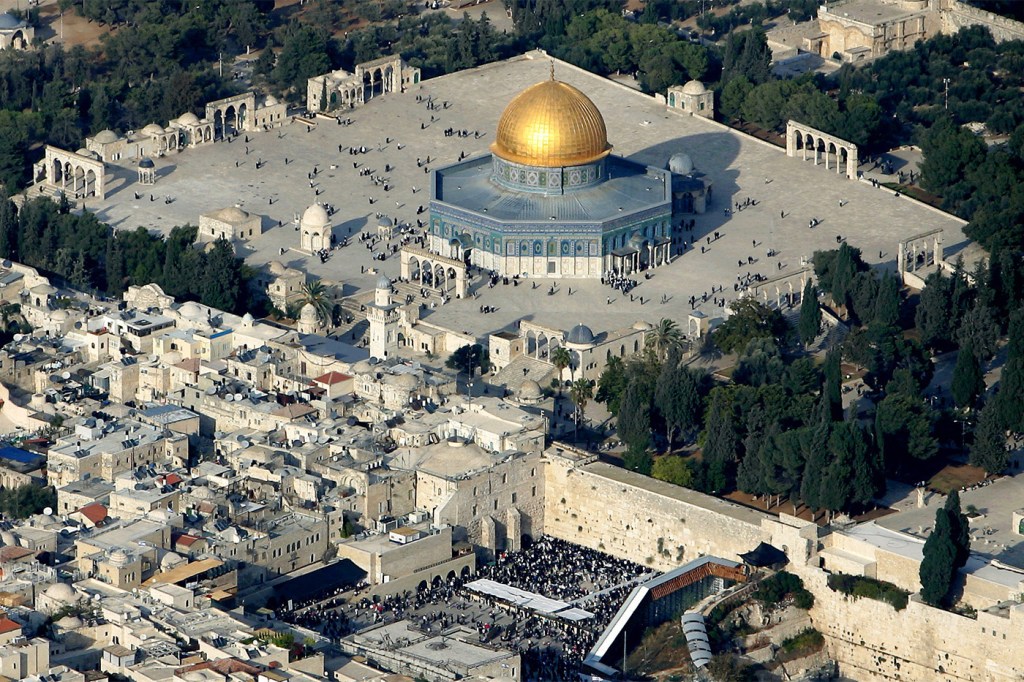

The dream of a two-state solution was first raised in 1937, 11 years before the formation of Israel. The idea was for Israelis and Palestinians to negotiate a settlement that would provide each with its own independent state, enabling them to live as neighbors in relative peace.

“It’s been the animating principle driving a majority of officials who know the conflict is not solvable by force,” Urman says. “The biggest challenge is that there are individuals and groups in the Palestinian and Israeli camps (and beyond, including Iran) that have successfully made the two-state solution much harder.”

The peace process peaked in 1993 when secret talks in Norway culminated in agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization. Those hopes were undermined by Palestinian terror attacks against Israel as well as by expanded settlement building by Israelis in the West Bank, a Palestinian territory.

Abrahms says a two-state solution has never been possible because Palestinian extremists have refused to accept a land settlement with Israel.

“There was a time when the majority Israeli population was in favor of making major territorial concessions to the Palestinians in exchange for peace,” says Abrahms, referring primarily to the 1993 Oslo Accords. “And then the terrorists torpedoed the peace process.

“When there was terrorism after 1993 it eroded Israeli interest in making territorial concessions,” Abrahms says. “Israelis do not trust the Palestinians to uphold any kind of agreement. The more terrorism there is, the less support there is in Israel for a two-state solution.”

Though Abrahms says he approves of the two-state model in theory, the harsh realities of the contested territory make him skeptical.

“I know that some people would disagree with me, but I do not believe that the Oslo peace process was very close to achieving a two-state solution,” Abrahms says. “You need to be realistic about what the sides would agree to.

“Hamas has opposed every single two-state-solution peace process, explicitly,” Abrahms says. “It has intentionally used terrorism in order to derail a two-state solution. And so there is no bargaining space.”

Abrahms notes that Hamas won parliamentary elections in 2006. One year later, Hamas seized power within Gaza during a bloody week-long conflict. In the aftermath, Israel and Egypt have maintained a blockade on Gaza that has essentially trapped more than 2 million residents (half of them 18 or younger) in an environment of poverty, according to humanitarian groups.

“Hamas was democratically elected, so its views on Israel are not a minority position,” Abrahms says. “And Hamas is not the only terrorist group there. There are more terrorist groups — Islamic Jihad, Lions’ Den — that are at least as radical as Hamas. They are not in favor of a two-state solution and have never been, and have actively undercut every two-state solution.”

Abrahms acknowledges that peace negotiations have been complicated by Israeli settlements in the West Bank, a larger landlocked Palestinian territory. The settlements have been approved by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who told CNN in January that he supports a two-state solution so long as the Palestinians have “none of the [military] powers that can threaten us.”

“People like to talk about this far-right government and the Israeli settlements in the West Bank, and how that supposedly scuttles a two-state solution,” Abrahms says. “But there was no two-state solution before this government and there was no two-state solution before the outgrowth of settlements in recent years.”

Urman notes that Israel controversially disengaged from Gaza in 2005, dismantling all 21 of its settlements from the region. Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon hoped that his decision would lead to greater security and eventual peace with the Palestinians. But the result has been more violence and instability, culminating in the recent attacks.

“The events of Oct. 7 have unified Israeli society in a way no internal leader ever could have,” Urman says. “Israelis are determined to eliminate any potential threat from Gaza, similar to what they did in Southern Lebanon in 2006 after Hezbollah killed and kidnapped Israeli soldiers. I think for Israelis, what happened in Gaza is just a terribly negative example of what happens when you unilaterally pull out of territories.”

Another issue embraced by Hamas is the “right of return” to Israel and the territories for those Palestinian refugees and their descendants who have been living in exile since the 1948 Palestine War.

The biggest challenge is that there are individuals and groups in the Palestinian and Israeli camps (and beyond, including Iran) that have successfully made the two-state solution much harder.

Dan Urman, director of the law and public policy minor at Northeastern

What is the way forward?

Based on his belief that the two-state solution is a non-starter, Abrahms says he has counseled U.S. administrations that the likelihood of resolving the Palestinian conflict is much smaller than the prospects of working to improve ties between Israel and Arab governments. Abrahms supported the 2020 Abraham Accords, negotiated by the Trump administration, that resulted in bilateral agreements for Israel with the United Arab Emirates as well as with Bahrain.

Abrahms hopes that the Biden administration will continue its efforts to develop a relationship between Israel and Saudi Arabia, which has put those negotiations on hold. Urman, too, sees the logic in building Israeli partnerships in the Middle East.

“Maybe Netanyahu and his fellow leaders can fast-track some of the new agreements, like an Abraham Accords part two,” Urman says. “As we have seen, it is nearly impossible for Israel to solve any of these issues alone. The Palestinians have not been a reliable partner, so maybe the Israelis will make these other deals with countries in the region, who can deliver on peace deals. Israeli agreements with Egypt and Jordan have not been perfect, but they have endured.”

Abrahms posits that news reports and images of Israeli troops marching into the territories may incite people in the Arab world to oppose their governments from partnering with Israel. Alternatively, he adds, a potential attack on Israel from the north by Hezbollah, a Lebanese political party and terrorist group, may galvanize Arab countries that are opposed to Hezbollah and its patron, Iran.

Urman draws perspective from the U.S. response to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

“I think most people agree that 9/11 provoked an overreaction from the U.S. — we invaded Iraq, we tortured people at home and abroad,” Urman says. “So this could go in any number of ways. The longer the war goes on, the further the pendulum swings. Depending on what the government learns about warning signs for the 10/7 attacks, this could also mark the end of Netanyahu’s political career.”

Taking the long view, Urman holds out hope for an outcome that defies prediction.

“I don’t think the idea of the two-state solution is dead,” Urman says. “I would say it has been shelved.”

Lefkovitz hasn’t abandoned that hope either.

“The longer things take and the more hearts are hardened, the more desperate and unlikely it feels that we’ll have peace,” she acknowledges. “But with the will, better leadership and adequate resources, we can hope for a political solution.”

Historically, Lefkovitz refers to the partnership between the U.S. and Japan that was unimaginable following the attacks on Pearl Harbor. She wonders who would have envisioned a cessation of The Troubles amid the decades of bloody conflict that divided Northern Ireland.

She brings up the story of her family.

“My father was liberated from Buchenwald,” Lefkovitz says of the World War II concentration camp. “When I was a child, the idea of going to Germany was anathema. But now I’ve been to Germany many times. It’s full of Israelis enjoying Berlin. The world turns on a dime sometimes.”

The trauma of Oct. 7 shrouds her dream of better days to come.

“Right now what I think we want most immediately is for the loss of innocent life to end and that there isn’t a return to some kind of unacceptable status quo,” Lefkovitz says. “The question is: Does the arc bend towards justice? Will we get to peace?”

Ian Thomsen is a Northeastern Global News features writer. Email him at i.thomsen@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter @IanatNU.